The post Cosmopolitan Magazine appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>The post appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>

The post appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>

The post Cosmopolitan Magazine appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>

The post Rudyard Kipling appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>

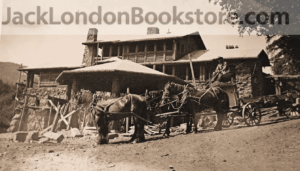

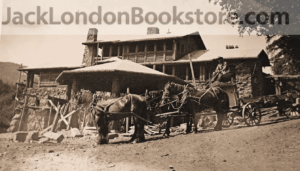

The post Wolf House appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>The post Call of the Wild – Audio Book appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>The post How Jack Got Out of Jail in Japan appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>Story of Japanese Official Red Tape That Sounds Like Comic Opera

A Vivid Glimpse of Judicial War-Time Methods in Mikado’s Realm

Tale that Hangs on Innocent Snapshots

SHIMONOSEKI, Wednesday, February 3 — I journeyed all day from Yokohama to Kobe to catch a steamer for Chemulpo, which last city is on the road to Seoul. I journeyed all day and all night from Kobe to Nagasaki to catch a steamer for Chemulpo. I journeyed back all day from Nagasaki to Moji to catch a steamer for Chemulpo. On Monday morning, in Moji, I bought my ticket for Chemulpo, to sail on Monday afternoon. Today is Wednesday, and I am still trying to catch a steamer for Chemulpo. And thereby hangs a tale of war and disaster, which runs the gamut of the emotions from surprise and anger to sorrow and brotherly love, and which culminates in arrest, felonious guilt and confiscation of property, to say nothing of monetary fines or alternative imprisonment.

For know that Moji is a fortified place, and one is not permitted to photograph “land or water scenery.” I did not know it, and I photographed neither land nor water scenery; but I know it now just the same.

Having bought my ticket at the Osaka Shosen Kaisha office, I tucked it into my pocket and stepped out the door. Came coolies carrying a bale of cotton. Snap went my camera, five little boys at play—snap again. A line of coolies carrying, and again snap, and last snap. For a middle-aged Japanese man, in European clothes and great perturbation, fluttered his hands prohibitively before my camera. Having performed this lion, he promptly disappeared.

“Ah, it is not allowed,” I thought, and, calling my rickshaw-m-an, I strolled along the street.

Later, passing by a two-story frame building, I noticed my middle-aged Japanese standing in the doorway. He smiled and beckoned me to enter. “Some chin-chin and tea,” thought I, and obeyed. But alas! it was destined to be too much chin-chin and no tea at all. I was in the police station. The middle-Japanese was what the American hobo calls a “fly cop.”

Great excitement ensued. Captains, lieutenants and ordinary policemen all talked at once and ran hither and thither. I had run into a hive of blue uniforms, brass buttons and cutlasses. The populace clustered like flies at doors and windows to gape at the “Russian spy.” At first it was all very ludicrous—“capital to while away some of the time ere my steamer departs,” was my judgment; but when I was taken to an upper room and the hours began to slip by, I decided that it was serious.

I explained that I was going to Chemulpo. “In a moment,” said the interpreter. I showed my ticket, my passport, my card, my credentials; and always and invariably came the answer, “In a moment.” Also, the interpreter stated that he was very sorry. He stated this many times. He made special trips upstairs to tell me he was very sorry. Every time I told him I was going to Chemulpo he expressed his sorrow, until we came to vie with each other, I in explaining my destination, he in explaining the state and degree of his emotion regarding me and my destination.

And so it went. The hour of tiffin had long gone by. I had had an early breakfast. But my appetite waited on his “In a moment” till afternoon was well along. Then came the police examination, replete with searching questions concerning myself, my antcedents, and every member of my family. All of which information was gravely written down. An unappeasable interest in my family was displayed. The remotest relatives were hailed with keen satisfaction and placed upon paper. The exact ascertainment of their antecedents and birthplaces seemed necessary to the point at issue, namely, the snaps I had taken of the four coolies carrying cotton, the five little boys playing and the string of coal coolies.

Next came my movements since my arrival in Japan. “Why did you go to Kobe?”

“To go to Chemulpo,” was my answer. And in this fashion I explained my presence in the various cities of Japan. I made manifest that my only reason for existence was to go to Chemulpo; but their conclusion from my week’s wandering was that I had no fixed place of abode. I began to shy. The last time the state of my existence had been so designated it had been followed by a thirty-day imprisonment in a vagrant’s cell. Chemulpo suddenly grew dim and distant, and began to fade beyond the horizon of my mind.

“What is your rank?” was the initial question of the next stage of the examination.

I was nobody, I explained, a mere citizen of the United States; though I felt like saying that my rank was that of traveler for Chemulpo. I was given to understand that by rank was meant business, profession.

‘Traveling to Chemulpo,” I said was my business; and when they looked puzzled I meekly added that I was only a correspondent.

Next, the hour and the minute I made the three exposures. Were they of land and water scenery? No, they were of people. What people? Then I told of the four coolies carrying cotton, the five small boys playing and the string of coal coolies. Did I stand with my back to the water while making the pictures? Did I stand with my back to the land? Somebody had informed them that I had taken pictures in Nagasaki (a police lie, and they sprang many such on me). I strenuously denied. Besides it had rained all the time I was in Nagasaki. What other pictures had I taken in Japan? Three—two of Mount Fuji, one of a man idling tea at a railway station. Where were the pictures? In the camera, along with the four coolies carrying cotton, the five boys playing and the string of coal coolies? Yes. Now, about those four coolies carrying cotton, the five small boys playing and the string of coal coolies? And then they rushed through the details of the three exposures, up and down, kick and forth, and crossways, till I wished that the coal coolies, cotton coolies and small boys had never been born. I have dreamed about them ever since, and I know I shall dream about them until I die.

Why did I take the pictures? Because I wanted to. Why did I want to? For my pleasure. Why for my pleasure?

Pause a moment, gentler reader, and consider. What answer could you give to such a question concerning any act you have ever performed? Why do you do anything? Because you want to; because it is your pleasure. An answer to the question, “Why do you perform an act for your pleasure?” would constitute an epitome of psychology. Such an answer would go down to the roots of being, for it involves impulse, volition, pain, pleasure, sensation, gray matter, nerve fibers, free will and determinism, and all the vast fields of speculation wherein man has floundered since the day he dropped down out of the trees and began to seek out the meaning of things.

And I, an insignificant traveler on my way to Chemulpo, was asked this question in the Moji police station through the medium of a seventh-rate interpreter. Nay, an answer was insisted upon. Why did I take the pictures because I wanted to, for my pleasure? I wished to take them—why? Because the act of taking them would make me happy. Why would the act of taking them make me happy? Because it would give me pleasure. But why would it give me pleasure? I hold no grudge against the policeman who examined me at Moji, yet I hope that in the life to come he will encounter the shade of Herbert Spencer and be informed just why, precisely, I took the pictures of the four coolies carrying cotton, the five small boys playing and the string of coal coolies. Now, concerning my family, were my sisters older than I or younger? The change in the line of questioning was refreshing, even though it was perplexing. But ascertained truth is safer than metaphysics, and I answered blithely. Had I a pension from the government? A salary? Had I a medal of service? Of merit? Was it an American camera? Was it instantaneous? Was it mine?

To cut a simple narrative short, I pass on from this sample of the examination I underwent to the next step in the proceedings, which was the development of the film. Guarded by a policeman and accompanied by the interpreter, I was taken through the streets of Moji to a native photographer. I described the location of the three pictures of the film of ten. Observe the simplicity of it. These three pictures he cut out and developed, the seven other exposures, or possible exposures, being returned to me undeveloped. They might have contained the secret of the fortifications of Moji for all the policemen knew; and yet I was permitted to carry them away with me, and I have them now. For the peace of Japan, let me declare that they contain only pictures of Fuji and tea-sellers.

I asked permission to go to my hotel and pack my trunks— in order to be ready to catch the steamer for Chemulpo. Permission was accorded, and my luggage accompanied me back to the police station, where I was again confined in the upper room listening to the “In a moments” of the interpreter and harping my one note that I wanted to go to Chemulpo.

In one of the intervals the interpreter remarked, “I know great American correspondent formerly.”

“What was his name?” I asked, politely.

“Benjamin Franklin,” came the answer; and I swear, possibly because I was thinking of Chemulpo, that my face remained graven as an image.

The arresting officer now demanded that I should pay for developing the incriminating film, and my declining to do so caused him not a little consternation.

“I am very sorry,” said the interpreter, and there were tears in his voice; “I inform you cannot go to Chemulpo. You must go to Kokura.”

Which last place I learned was a city a few miles in the interior.

“Baggage go?” I asked.

“You pay?” he countered.

I shook my head.

“Baggage go not,” he announced.

“And I go not,” was my reply.

I was led downstairs into the main office. My luggage followed. The police surveyed it. Everybody began to talk at once. Soon they were shouting. The din was terrific, the gestures terrifying. In the midst of it I asked the interpreter what they had decided to do, and he answered, shouting to make himself heard, that they were talking it over.

Finally rickshaws were impressed, and bag and baggage transferred to the depot. Alighting at the depot at Kokura, more delay was caused by my declining to leave my luggage in the freight office. In the end it was carted along with me to the police station, where it became a spectacle for the officials.

Here I underwent an examination before the Public Procurator of the Kokura District Court. The interpreter began very unhappily, as follows:

“Customs different in Japan from America; therefore you must not tell any lies.”

Then was threshed over once again all the details of the four coolies carrying cotton, the five small boys playing and the string of coal coolies; and I was committed to appear for trial next morning.

And next morning, bare-headed, standing, I was tried by three solemn, black-capped judges. The affair was very serious. I had committed a grave offense, and the Public Procurator stated that while I did not merit a prison sentence, I was nevertheless worthy of a fine.

After an hour’s retirement the judges achieved a verdict. I was to pay a fine of five yen, and Japan was to get the camera. All of which was eminently distasteful to me, but I managed to extract a grain of satisfaction from the fact that they quite forgot to mulct me of the five yen. There is trouble brewing for somebody because of those five yen. There is the judgment. I am a free man. But how are they to balance accounts?

In the evening at the hotel the manager, a Japanese, handed me a card, upon which was transcribed: Reporter of the “Osaka Asahi Shimbun.” I met him in the reading-room, a slender, spectacled, silk-gowned man, who knew not one word of English. The manager acted as interpreter. The reporter was very sorry for my predicament. He expressed the regret of twenty other native correspondents in the vicinity, who in turn, represented the most powerful newspapers in the empire. He had come to offer their best offices; also to interview me.

The law was the law, he said, and the decree of the court could not be set aside; but there were ways of getting around the law. The voice of the newspapers was heard in the land. He and his fellow correspondents would petition the Kokura judges to auction off the camera, he and his associates to attend and bid it in at a nominal figure. Then it would give them the greatest pleasure to present my camera (or the Mikado’s, or theirs) to me with their compliments.

I could have thrown my arms about him then and there—not for the camera, but for brotherhood, as he himself expressed it the next moment, because we were brothers in the craft. Then we had tea together and talked over the prospects of war. The nation of Japan he likened to a prancing and impatient horse, the Government to the rider, endeavoring to restrain the fiery steed. The people wanted war, the newspapers wanted war, public opinion clamored for war; and war the Government would eventually have to give them.

We parted as brothers part, and without wishing him any ill-luck, I should like to help him out of a hole some day in the United States. And here I remain in my hotel wondering if I’ll ever see my camera again and trying to find another steamer for Chemulpo.

P. S.—Just received a dispatch from the United States Minister at Tokyo. As an act of courtesy, the Minister of Justice will issue orders today to restore my camera!

P. S.—And a steamer sails tomorrow for Chemulpo.

The post How Jack Got Out of Jail in Japan appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>The post Jack London Ranch Film -1916 appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>

The post LOVE on the Yalu River – 1904 appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>

The post wolfhousephoto.jpg appeared first on Jack London Bookstore.

]]>