Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() AYBREAK on a glassy sea and startled flying fish are struggling to

fly in the absence of wind. Seaward the destroyers, like cardboard silhouettes,

pass across the blood-red orb of the sun just clearing the horizon.

AYBREAK on a glassy sea and startled flying fish are struggling to

fly in the absence of wind. Seaward the destroyers, like cardboard silhouettes,

pass across the blood-red orb of the sun just clearing the horizon.

Ahead still steams our convoying battleship, the

Louisiana. Astern, in line at half speed, steam our three sister

transports. Coastward are the blinking lighthouse, a long blur of land that

with growing day resolves itself into a breakwater, a low shore, a towered

city, and a harbor of many battleships. So many battleships are there that they

have spilled out of the crowded harbor until several times as many are in the

open roadstead. And there are naval supply ships, hospital ships, a wireless

ship, and colliers.

And overhead, to give the last touch of modern

war to the scene, a naval hydroplane burrs like some gigantic June bug through

the gray of day.

Here, where Cortez burned his ships long

centuries gone, and where Scott bombarded and took the city two generations

ago, lie Uncle Sam's warships with every man on his toes. Yes, and every

soldier gazing eagerly ashore from crowded transports is on his toes.

All is peaceful, yet the feeling one gets of the

many ships, the burring flying machines, and the thousands of men is that of

being on tiptoe to begin.

On Tiptoe for Excitement

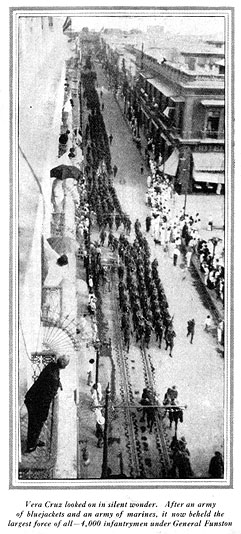

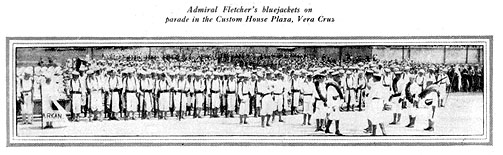

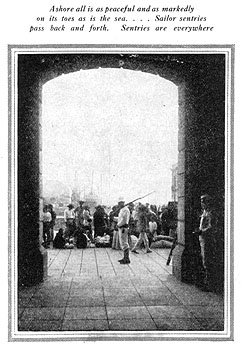

ASHORE

all is as peaceful and as markedly on its toes as is the sea. Everywhere

marines and bluejackets are cooking breakfast. From the roof of the Terminal

Hotel sailors are wigwagging. Sailor aids of sailor officers gallop back and

forth on commandeered Mexican horses, and commandeered automobiles dash by with

the officers on the seats and armed sailors standing on the running boards.

American women, quite like American women at

home, with never an earmark of being refugees from the interior of Mexico, are

breakfasting on the cool arcaded sidewalks of hotels bordering the Plaza.

Overhead whirl huge electric fans along the lines of the tables where our women

breakfast so composedly and sailor sentries pace back and forth. Sentries are

everywhere. So are the newsboys with their eternal extras. Through the

confusion of bootblacks, flower sellers, and picture post-card peddlers stride

naval and marine officers in duck and khaki, and from the hips of all of them

big revolvers and automatics swing in leather holsters. Down the street, in the

thick of mule carts and mounted sailors, pass bareheaded Mexican women

returning from market with big fish unwrapped and glistening in the sun.

In the Hotel Diligencia's bedroom where I write

these lines under lofty, gold-edged beams, there is a spatter of fresh bullet

holes on the blue wall. In the lace-patterned mosquito canopy over my bed is a

line of irregular rents which, folded as they were originally, show the path of

a single bullet. The glass of the French windows that open on the balcony is

perforated by many bullets. The wrecked door shows how our sailors entered

behind the butts of their rifles in the course of the street fighting and house

cleaning. From the fretted balcony one can see the ruins of plate glass and

mirrors in the shops and hotels fronting the street and plaza.

Feats of Sailor Ingenuity

MEXICAN

officers seem to have notions different from ours in the matter of prosecuting

war. When the landing of our forces was imminent, General Maas, who was the

Federal commander at Vera Cruz, released the criminal portion of the prisoners

confined in the fortress of San Juan de Ulloa. These were the hard cases, the

murderers and robbers and men guilty of violent and terrible crimes. The

politicals General Maas was very careful not to release. And when our forces

did land, General Maas fled for the hinterland before the fighting began,

having first instructed his soldiers to shift for themselves. While the

released prisoners did take some part in the street fighting and housetop

sniping, in the main they devoted themselves to pillage. Hard cash was what

they went after, as for instance the smashed safes in Mr. Tansey's office at

the Pierce Oil Refinery attest. Falling back before our men, these convicts

terrorized the country people, looting everything of value and not refraining

from attacking the women. So merciless were they that the outraged peons

captured and summarily executed two of them who had lingered behind their

fellows.

Yes, there is a decided evolution in technique of

war as practiced by modern soldiers. Our fighting ships are ten and fifteen

million-dollar electrical, chemical, and mechanical laboratories, and they are

manned by scientists and mechanicians. They had the street cleaners out ere the

bodies were picked up. In a matter of several hours they repaired and ran the

two scrapped locomotives which the Federals had thought too worthless to run

out. And while this was going on other sailors were rigging short wireless

masts on top of a day coach and equipping the car with a complete wireless

apparatus.

The ice plant of Vera Cruz had broken down, and

Vera Cruz without ice was a condition not to be tolerated, so by afternoon the

sailors had repaired the plant, and the sick and wounded as well as all the

rest of the city had its ice again. When four knocked-down automobiles were

discovered, volunteers were called for and in less than three hours the cars

were assembled and were being driven about the city on military business by the

jackies who had assembled them. As civilians remarked, our sailors are able to

practice all trades and professions under the sun with the sole exception of

wet-nursing. Even so, I have seen them carrying Mexican babies for tired

mothers across the stretch of railroad which the Federals destroyed.

And the way our sailors drove and rode horses,

mules, and burros was even more wonderful than their other achievements. They

came off our ships sailors; they will return soldiers.

Navigating a Mexican Horse

THEY

tell of one young sailor who mounted a commandeered horse in a lull in the

fighting. He had not minded the fighting, but it was with somewhat of the

spirit one embarks on a forlorn hope that he got his legs astride the animal.

"Well," he said as he settled himself in the saddle,

"commence."

"What do I do now?" asked another

jacky, mounting at the Plaza.

"Go ahead half speed," was the advice.

"Keep your helm amidships to the corner, then starboard your helm and

proceed under forced draft."

It is true that, when under forced draft, the

jackies hold on inelegantly by main strength of gripping legs; but the point is

that they do hold on. I have looked in vain to see one of them separated from

his mount. One misadventure only have I witnessed: and then the sailor, at a

dead gallop, abruptly put his helm hard over at a sharp corner and capsized his

four-legged craft. When the band struck up "The Star-Spangled Banner"

at Admiral Fletcher's flag raising, a marine, mounted on a Mexican horse, took

its ear and turned it forward. "Listen to that, hombre," said the

marine; "that's real music. It's American music."

On the Arkansas occurred an incident which

serves to show to what extent our men were on their toes prior to landing.

Lieutenant Commander Keating of the Arkansas battalion had selected the

best and strongest of his men for shore work. The men who were not selected

were sad and sore. At the last there remained but one man more to select, and

two of the youngsters urged what was considered equal claims of health,

strength, and record. How to decide between them was beyond the Lieutenant

Commander. The boys themselves suggested the way. They put on boxing gloves and

fought for it. Those who saw the battle aver that it was the hottest bout

between amateurs they had ever witnessed. At the end of four rounds it was a

draw and Lieutenant Commander Keating was more perplexed than ever. His final

solution of the problem was the only way it could be fairly solved. He took

both lads. Later he reported that, as in everything else, they had played

equally splendid parts in shore fighting and shore work.

Incredible Marksmanship

ONLY

very brave men or fools without any knowledge of modern shell fire could have

fired upon our sailors and marines from the Naval School. Broadside on, at

close range, lay the Chester. When the first shots were fired upon our

men, the Chester went into action for a hot five minutes. Had the

taxpayer at home witnessed the way those upper story windows were put out by

the Chester's shells, he would never again grudge the money spent in

recent years in target practice. Onlookers say that it reminded them of Buffalo

Bill's exhibitions of rifle shooting.

The outside of the Naval School was little

damaged. Inside it was a vast wreck. Practically every shell entered by way of

the windows and exploded inside. When I visited the building, which is a huge

affair, many buzzards were appropriately perched on the broken parapets.

Inside, through burst floors, rent ceilings, and masses of fallen masonry, one

could trace the flight of the shells through massive partitions to the spots

where they had exploded.

There was all the evidence of the hot five

minutes. In the big patio were great heaps of fallen cement balustrades from

second-story balconies. Some of the shells went clear through the building,

crossed the patio, and burst in the rear rooms. Many years had been consumed in

the constructions, equipping, and organizing of that building, and in five

minutes it was to all intents and purposes destroyed. Such is the efficiency of

twentieth century war machinery. Laboratories furnished with most delicate and

expensive instruments were knocked into cocked hats by single shells.

One lecture room was filled with beautiful models

of ships. One model, of a full-rigged ship, twenty-five feet in length, with

skysail yards and all sails set, precise in every minutest detail aloft and

alow, was undamaged save for a rent in her mainsail from a fragment of shell.

Other and smaller models, shattered and dismasted, covered the floor with all

the destruction of an armada. On a blackboard was scrawled "Captured by

the U. S. S. New Hampshire, April 22, 1914."

In other lecture rooms, on blackboards alongside

academic problems of war as demonstrated by Mexican cadets, were chalked

records of boys from the Utah, the San Francisco, and the

Arkansas.

Bloodstained cots and pillows showed that more

than roof beams and masonry had been shattered. Through knee-deep riffraff of

discarded uniforms, sketches, maps, and examination papers, clucked and

strutted on live thing left from the bombardment—a trip Mexican rooster that

bore all the marks of a fighting cock.

But it was in the second story that the worst

devastation was wrought. Roofs, floors, and walls were perforated and smashed

to chaos. "Mind your foot," was the constant cry as one trod gingerly

over débris and wove in and out among yawning holes.

The touch of the eternal feminine was not

missing. My lady's boudoir seemed to have received the severest fire. Fourteen

shell holes punctured the walls, the ceiling had partly fallen in, a great hole

gaped in the floor, and one shell had burst directly on the brass bed. The

floor was hillocked with masses of masonry and broken furniture, and all about

were scattered pretties and fripperies of the lady—empty jewel cases, powder

puffs, silver-mounted brushes. Most conspicuous of all was a pair of red,

high-heeled Spanish slippers.

Aboard the Rescue Train

DOWN in

the railroad station, where I boarded the rescue train that runs out each day

to the Federal lines, our sailors and marines were cooking, washing clothes,

and teaching the Mexican youth how to pitch baseball. All along the track,

until the country was reached, our men were encamped and performing sentry

duty.

A guard of bluejackets, under the command of

Lieutenant Fletcher of the Florida, manned the train. The engine was run

by our enlisted men, who had repaired it, as was also the wireless by the men

who had installed it. Even the porter of the Pullman car was an unmistakable

American negro.

Two miles beyond our last outpost we came to the

break where the Federals had torn up two miles of track, burning the ties and

carrying the rails away with them. Here, also, was a blockhouse of advanced

Federal outposts.

Under a white Turkish towel, carried by a sailor,

Lieutenant Fletcher met and conferred with the Mexican Lieutenant in charge.

The latter was small, stupid-tired, and a greatly embarrassed sort of man. The

contrast between the two Lieutenants was striking. The Mexican Lieutenant

strove to add inches to himself by standing on top of a steel rail. But in

vain. The American still towered above him. The American was—well, American.

Little of Mexican or of Spanish was in the other. It was patent that he was

mostly Indian. Even more of Indian was in the ragged, leather-sandaled soldiers

under him. They were short, squat, patient-eyed, long-enduring as the way of

the peon has been even in the long centuries preceding Cortez, when Aztec and

Toltec enslaved him to burden bearing.

The Oxlike Peon Soldier

ONE could not help being sorry for these sorry soldier Indians, who slouched awkwardly about while our Lieutenant scanned the far track across the break in the hope of some sign of our countrymen fleeing from the capital. Sorry soldier Indians they truly were. When I though of our own fine boys of the fleet and the army back in Vera Cruz, it seemed to me that it could not be war, but murder. What chance could such lowly, oxlike creatures, untrained themselves and without properly trained officers, have against our highly equipped, capably led young men? These soldiers of the peon type are merely descendants of the millions of stupid ones who could not withstand the several hundred ragamuffins of Cortez and who passed stupidly from the hash slavery of the Montezumas to the no less harsh slavery of the Spaniards and of the later Mexicans.

But Even Peons Can Hurl Death

AND

yet one must not forget that each one of these sorry soldiers bore a modern

rifle, the cartridges for which, loaded with smokeless powder, are capable of

propelling a bullet to kill at a mile's distance and farther, and, at closer

range, to perforate the bodies of two or three men. Also, each of these sorry

soldiers, at command, by the mere crooking of First Editions fingers, could release

far-flighted messengers of death. Also, the mark of the cross, rightly applied

to the steel-jacketed nose of the bullet, can turn that bullet into a dumdum

that makes a small hold on entering a man's body and a hole the size of a soup

plate on leaving. It requires no intelligence thus to notch a bullet. Even a

peon can do it.

War is a silly thing for a rational, civilized

man to contemplate. To settle matters of right and justice by means of

introducing into human bodies foreign substances that tear them to pieces is no

less silly than ducking elderly ladies of eccentric behavior to find out

whether or not they are witches. But—and there you are—what is the rational

man to do when those about him persist in settling matters at issue by violent

means?

Even Peace Lovers Must Be Prepared

I AM a rational man. I firmly believe in arbitrament by police magistrates and civil courts. Nevertheless, on occasion, I find myself in contact with men who are prone, say, to rob me of my purse, and who elect to do it by violent and disruptive means. So, on such occasions, I am compelled to carry an automatic in order to dispute with such men my path in life which they are blocking and ambuscading. Personally, and for a lazy man, carrying a big automatic is a confounded nuisance. I hope for the day to come when it will not be necessary for any man to carry an automatic. But in the meantime, preferring to be a live dog rather than a dead lion, I keep thin oil on my pistol and try it out once in a while to make sure that it is working.

As it is with rational men to-day so it is with

nations. The dream of a world police force and of a world court of arbitration

will some day be realized. But that day is not to-day. What is is. And to cope

with what is, it behooves nations to keep thin oil on their war machinery and

know how to handle it.

Texas was long notorious as a gun-fighting State.

To-day it is against the law for a man to carry a revolver in Texas. Times do

change. But there is always the time between times. As one regarded the Mexican

Lieutenant with his peon soldiers, it was patent that the old order still

obtained, and that each peon was equipped with sufficient cartridges to destroy

the rationality of a hundred men like me.

The Man He Could Lick

AND we

stood there under our white Turkish towel, surrounded by armed men, and quested

across a stretch of ruined railroad for the sight of some of our own men,

women, and children making their way down to the coast from mobs that looted,

plundered, and cried death to them.

"I've found him at last," said a

friend, a Texas civilian and ex-roughrider.

All the way out on the train he had been lining

himself up against one and another of the husky broad-shouldered sailor boys

and lamenting that he could not find a man he could lick. Now he gazed with

satisfaction at the little Mexican Lieutenant and muttered in my ear: "I

just wish it was up to him and me to settle this whole war. Take him on on any

terms—bite, gouge, or anything up to locking us, stripped, in a dark

room."

The Goal of the Refugees

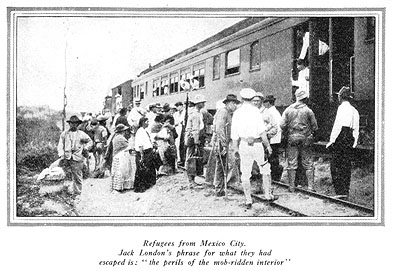

A

TRAIN appeared in the distance between green walls of jungle. Through our

glasses we could make out parasols and sunshades that advertised women of our

race who had escaped the perils of the mob-ridden interior.

Permission was reluctantly accorded us, and we

advanced a mile along the destroyed track to meet our countrymen. Glad as we

were to see them, their gladness at seeing white men from the coast was almost

pathetic. For three days and nights they had not had their clothes off nor lain

in a bed, nor had they ever been certain of their lives during that time.

It seems the Mexican officers have a very simple

and clever technique of waging war on civilians of the United States. The

officers themselves rob civilians of revolvers. This enables the next mob of

death-shouting Mexicans to put words into deeds without the slightest risk of

being hurt. Of course the Mexican army cannot be held responsible for all the

actions and the murders committed by such mobs. Also, officers are richer by

the number of weapons they accumulate from fleeing Americans.

By the time our refugees reached the train and

saw the American uniform they were stating that it was the finest thing they

had ever seen in their lives. As the train backed into Vera Cruz the landscape

continued to grow more beautiful, for it was covered everywhere with sailors

and marines on sentry duty or in camp. But the sight of the inner and outer

harbors filled with our warships was the finishing stroke.

Experiences at Mexican Hands

SAID one

of the refugees, a doctor: "I just wish the fellows at Washington who are

running things could have had our experience. It would change their views on

diplomacy and on army and navy appropriation bills. I tell you, if they had

been robbed and mobbed and thrown into jail along with their wives and

children, and heard the roar going up all about them of 'Muerto los gringos!'

and then, finally, got down the country as we have, with their tongues hanging

out, and seen these warships and bluejackets—I tell you they couldn't get back

to the States quick enough to start working for a larger army and

navy."

The views of American residents of Mexico should

be of value at the present time, and I shall repeat them without comment to

show how blows the wind with those whose personal interests are vitally

involved.

"Somehow," said one of them, "we

don't enjoy seeing the United States call on the A B C class in Spanish and

Portuguese to help her out of this mess."

Another declared: "This waiting and

watching, our Fabian offensiveness, is a whole lot easier at Washington than at

Vera Cruz. Besides, I can't help working over what the Mexicans have done or

are doing to my wolfhound. That dog—why sir, just standing on her four legs,

she could reach her head over and take anything from the center of this

breakfast table."

"How are the people at home feeling

now?" inquired a refugee. "They got us into this mess. Are they going

to get us out of it?"

Refugee Criticism of Policy

THE

thorough agreement of all American residents is that the present crisis was

brought on by the policy of our Government, and that the only way out is to go

on through. The taking of Vera Cruz by the naval forces of the United States

precipitated the bad feeling against Americans that has been fermenting during

the past several years, and if the United States should recede from its present

position, it will forever be impossible for Americans again to live in

Mexico.

As one man, a twenty-year resident, said:

"I've lived here ever since I was man-grown. I know what I am talking

about. Humpty Dumpty has had a great fall. Chile, Brazil, and Argentina can

never put him together again. Only our army and our navy can put us Americans

back again and insure us a fair deal. And when I speak of ourselves I mean the

people who have made Mexico what it is to-day, or, rather, what it was the

other day before the Tampico flag incident. More than any other country—than

all other countries added together—have we put in the capital, the brains, and

the technical skill; we've supplied the mechanical engineers, the mining

engineers, the agricultural chemists, and the scientific farmers. By virtue of

what we have done in Mexico we have a right here, and we should be protected in

that right, expecially since our Government by its own action has endangered

that right."

"Just Turn Texas Loose"

SAID a

man of action, his State obvious by his remark: "Never mind the rest of

the United States. Just turn Texas loose and we'll lick them to a frazzled

finish."

"Huh!" from another man of action.

"Send a single man upcountry with a big bag of money and the whole thing

could be settled out of hand."

Another long dweller in the land: "I've

lived in Oaxaca fifteen years, and I make the statement, founded on personal

knowledge, that 80 per cent of the middle class and educated Mexicans

throughout Oaxaca would hail intervention by the United States. They are tired

of this era of continual revolution."

A mining engineer: "My people represent

millions invested in development. We are not afraid of the next step the United

States may take. What we are afraid of is that she may not take any

step."

A locomotive engineer: "Well, our country

has got us in bad. It's up to her to get us out good."

A marine guarding a sand hill: "This is a

hell of a war."

Our Diplomatic Utterances

A

BUSINESS man from the City of Mexico: "They have insulted me, broken

windows of my home, and looted my store. Also they have robbed me of my

automobile; on the way down to Vera Cruz a Mexican officer took my revolver

away from me. At the present moment I have two hundred pesos and the clothes I

stand up in, and my country is talking compromise."

Another business man: "For years the United

States has been watching and waiting. Now it has made one step into Mexico,

imperiled all our lives, caused us incalculable losses of property and personal

possessions, and is hesitating whether to withdraw form that one step or

not."

A university man: "I thought I understood

the English language. I find now that I don't. My brain is fuzzy and trying to

get ordinary sense out of our diplomatic uutterances."

An officer of marines: "We've lost many

times as many sailors as were lost in the Spanish-American War, and yet this is

not war. We have merely occupied a customhouse and courteously taken the

government of Vera Cruz out of the hands of Mexican officials."

A staff officer of the Second Division: "It

is not a question with me of the merits or demerits of the affair. I am the

servant of my country. It spent a whole lot of money training me. When it says

advance, I advance; when it says retreat, I retreat. Nevertheless, I remember

that my old father was always fond of quoting Davy Crockett's 'Be sure you are

right and then go ahead.' Well, we've come ahead from Galveston to Vera Cruz.

And here we stop. What's the matter? Did the United States go ahead and then

find out that it was not right?"

Another officer: "It wasn't the flag

incident at Tampico; it was the sum of many incidents preceding the flag

incident."

A lawyer: "But, as a jury decided long ago

in England, two hundred blackbirds do not make a black horse."

"And twenty thousand looted refugee

Americans plus a thousand insults to our nation make a sum no larger than the

smallest of the parts, and therefore no casus belli," was the retort of a

fellow lawyer.

"Whisper!" says an American farmer from

Cordova. "Within a week look to see Huerta in Vera Cruz, safely on board a

foreign warship, and headed for Europe."

Again is limned the lurid picture of that Indian

dictator in his high city—with Villa threatening death from the North, with

Zapata unpacified in the South, with a great treasure cached in Europe—trying

to solve the desperate problem of how to get from his high city to the sea

coast and to Europe.

"Against American shells?" queries the

latest newspaper man from the United States.

"No," answers the refugee. "Nor

against Villa. He is sandbagging the palace to withstand attacks from the

populace!"

From the May 23, 1914 issue of Collier's magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.