Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

When Alice Told Her Soul

By Jack London

Illustrated by G. Patrick Nelson

| Jack London's last writings were a number of short stories dealing with life in the South Pacific, a region of the globe which is the scene of a great deal of his most vivid and characteristic work. The utterly virile quality of the romance of the Islands deeply fascinated him, and he has shown them to us as a land of matchless adventure. Especially well did he know Hawaii, for a considerable portion of each of his last years was spent there. The following diverting tale, with its Honolulu setting, will be followed at intervals by the remainder of Mr. London's posthumous work. |

THIS, of Alice Akana, is an affair of Hawaii, not of this day but of

days recent enough, when Abel Ah Yo preached his famous revival in Honolulu and

persuaded Alice Akana to tell her soul. But what Alice told concerned itself

with the earlier history of the then surviving generation.

THIS, of Alice Akana, is an affair of Hawaii, not of this day but of

days recent enough, when Abel Ah Yo preached his famous revival in Honolulu and

persuaded Alice Akana to tell her soul. But what Alice told concerned itself

with the earlier history of the then surviving generation.

For Alice Akana was fifty years old, had begun

life early, and, early and late, lived it spaciously. What she knew went back

into the roots and foundations of families, businesses, and plantations. She

was the one living repository of accurate information that lawyers sought out,

whether the information they required related to land boundaries and land

gifts, or to marriages, births, bequests, or scandals. Rarely, because of the

tight tongue she kept behind her teeth, did she give them what they asked, and

when she did was when only equity was served and no one was hurt.

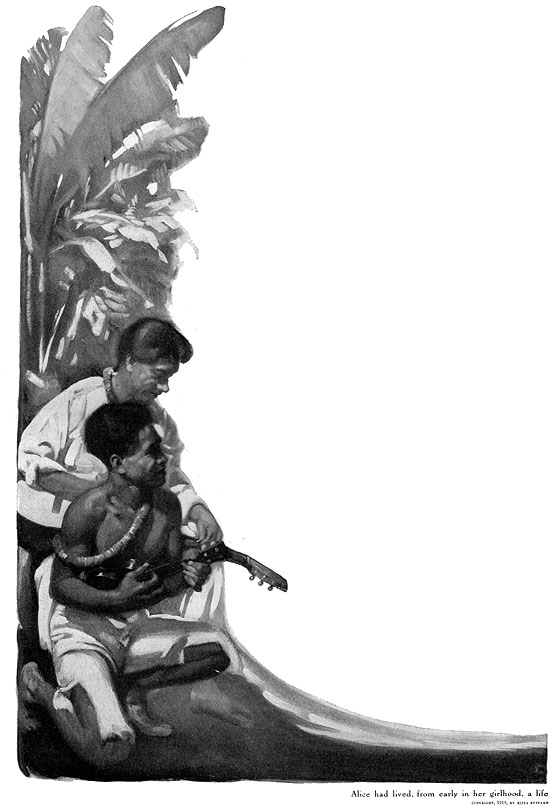

For Alice had lived, from early in her girlhood,

a life of flowers and song and wine and dance, and, in her later years, had

herself been mistress of these reve s by office of mistress of the

hula-house. In such atmosphere, where mandates of God and man and caution are

inhibited, and where woozled tongues will wag, she acquired her historical

knowledge of things never otherwise whispered and rarely guessed. And her tight

tongue had served her well, so that, while the old-timers knew she must know,

none ever heard her gossip of the times of Kalakaua's boat-house, or of the

high times of officers of visiting war-ships, or of the diplomatists and

ministers and consuls of the countries of the world.

So, at fifty, loaded with historical dynamite

sufficient, if it were ever exploded, to shake the social and commercial life

of the Islands, still tight of tongue, Alice Akana was mistress of the

hula-house, manageress of the dancing girls who hula'd for royalty, for

luaus (feasts), house-parties, poi-suppers, and curious tourists.

And, at fifty, she was not merely buxom but short and fat in the Polynesian

peasant way, with a constitution and lack of organic weakness that promised

incalculable years. But it was at fifty that she strayed, quite by chance of

time and curiosity, into Abel Ah Yo's revival meeting.

Now Abel Ah Yo, in his theology and

word-wizardry, was a much mixed personage. In his genealogy, he was much more

mixed, for he was compounded of one-fourth Portuguese, one-fourth Scotch,

one-fourth Hawaiian, and one-fourth Chinese. The pentecostal fire he flamed

forth was hotter and more variegated than could any one of the four races of

him alone have flamed forth. For in him were gathered together the canniness

and the cunning, the wit and the wisdom, the subtlety and the rawness, the

passion and the philosophy, the agonizing spirit-groping and the legs up to the

knees in the dung of reality of the four radically different breeds that

contributed to the sum of him. His, also, was the clever self-deceivement of

the entire clever compound.

When it came to word-wizardry, he was master of

slang and argot of four languages. For in Abel Ah Yo were the live verbs

and nouns and adjectives and metaphors of all four. Of no race, a mongrel

par excellence, a heterogeneous scrabble, the genius of the admixture

was superlatively Abel Ah Yo's. Like a chameleon, he titubated and scintillated

grandly between the diverse parts of him, stunning by frontal attack and

surprising and confounding by flanking sweeps and mental homogeneity of the

more simply constituted souls who came in to his revival to sit under him and

flame to his flaming.

Abel Ah Yo believed in himself and his mixedness

as he believed in the mixedness of his weird concept that God looked as much

like him as like any man, being no mere tribal god but a world-god that must

look equally like all races of all the world, even if it led to piebaldness.

And the concept worked. Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Hawaiian, Porto Rican,

Russian, English, French—members of all races—knelt without friction, side by

side, to his revision of Deity.

Himself in his tender youth an apostate to the

Church of England, Abel Ah Yo had for years suffered the lively sense of being

a Judas-sinner. Essentially religious, he had forsworn the Lord. Like Judas,

therefore, he was. Judas was damned. Wherefore he, Abel Ah Yo, was damned, and

he did not want to be damned. So, quite after the manner of humans, he squirmed

and twisted to escape damnation. The day came when he solved his escape. The

doctrine that Judas was damned, he concluded, was a misinterpretation of God,

who, above all things, stood for justice. Judas had been God's servant,

specially selected to perform a particularly nasty job. Therefore, Judas, ever

faithful, a betrayer only by divine command, was a saint. Ergo, he, Abel Ah Yo,

was a saint by very virtue of his apostasy to a particular sect, and he could

have access with clear grace any time to God.

This theory became one of the major tenets of his preaching, and was especially efficacious in cleansing the consciences of the backsliders from all other faiths, who else, in the secrecy of their subconscious selves, were being crushed by the weight of the Judas-sin. To Abel Ah Yo, God's plan was as clear as if he, Abel Ah Yo, had planned it himself. All would be saved in the end, although some took longer than others and would win only to back seats. Man's place in the ever-fluxing chaos of the world was definite and preordained—if by no other token, then by denial that there was any ever-fluxing chaos. This was a mere bugbear of mankind's addled fancy, and, by stinging audacities of thought and speech, by vivid slang that bit home, by sheerest intimacy into his listeners' mental processes, he drove the bugbear from their brains, showed them the loving clarity of God's design, and, thereby, induced in them spiritual serenity and calm.

What chance had Alice Akana, herself pure and

homogeneous Hawaiian, against his subtle, democratic-tinged,

four-race-engendered, slang-munitioned attack? He knew, by contact, almost as

much as she about the waywardness of living and sinning—having been singing

boy on the passenger-ships between Hawaii and California, and, after that,

bar-boy, afloat and ashore, from the Barbary Coast to Heinie's Tavern. In point

of fact, he had left his job of Number One bar-boy at the University Club to

embark on his great preachment revival.

So, when Alice Akana strayed in to scoff, she

remained to pray to Abel Ah Yo's god, who struck her hard-headed mind as the

most sensible god of which she had ever heard. She gave money into Abel Ah Yo's

collection-plate, closed up the hula-house, and dismissed the hula dancers to

more devious ways of earning a livelihood, shed her bright colors and raiments

and flower garlands, and bought a Bible.

It was a time of religious excitement in the

purlieus of Honolulu. The thing was a democratic movement of the people toward

God. Place and caste were invited, but never came. The stupid lowly and the

humble lowly only went down on their knees at the penitent form, admitted their

pathological weight and hurt of sin, eliminated and purged all their

bafflements, and walked forth again upright under the sun, childlike and pure,

upborne by Abel Ah Yo's god's arm around it. In short, Abel Ah Yo's revival was

a clearing-house for sin and sickness of spirit, wherein sinners were relieved

of their burdens and made light and bright and spiritually healthy again.

But Alice was not happy. She had not been

cleared. She bought and dispersed Bibles, contributed more money to the plate,

contralto'd gloriously in all the hymns, but would not tell her soul. In vain,

Abel Ah Yo wrestled with her. She would not go down on her knees at the

penitent form and voice the things of tarnish within her—the ill things of

good friends of the old days.

"You cannot serve two masters," Abel Ah

Yo told her. "Hell is full of those who have tried. Single of heart and

pure of heart must you make your peace with God. Not until you tell your soul

to God right out in meeting will you be ready for redemption. In the mean time,

you will suffer the canker of the sin you carry about within you."

Scientifically, though, he did not know it and

though he continually jeered at science, Abel Ah Yo was right. Nor could she be

again as a child and become radiantly clad in God's grace until she had

eliminated from her soul, by telling, all the sophistications that had been

hers, including those she shared with others. In the Protestant way, she must

bare her soul in public, as in the Catholic way it was done in the privacy of

the confessional. The result of such baring would be unity, tranquillity,

happiness, cleansing, redemption, and immortal life.

"Choose!" Abel Ah Yo thundered.

"Loyalty to God, or loyalty to man!"

And Alice could not choose. Too long had she kept

her tongue locked with the honor of man.

"I will tell all my soul about myself,"

she contended. "God knows I am tired of my soul and should like to have it

clean and shining once again as when I was a little girl at Kaneohe."

"But all the corruption of your soul has

been with other souls," was Abel Ah Yo's invariable reply. "When you

have a burden, lay it down. You cannot bear a burden and be quit of it at the

same time."

"I will pray to God each day and many times

each day," she urged. "I will approach God with humility, with sighs,

and with tears. I will contribute often to the plate, and I will buy Bibles,

Bibles, Bibles without end."

"And God will not smile upon you,"

God's mouthpiece retorted. "And you will remain weary and heavy-laden. For

you will not have told all your sin, and not until you have told all will you

be rid of any."

"This rebirth is difficult," Alice

sighed.

"Rebirth is even more difficult than

birth." Abel Ah Yo did anything but comfort her. "Not until you

become as a little child."

"If ever I tell my soul, it will be a big

telling," she confided.

"The bigger the reason to tell it,

then."

And so the situation remained at deadlock, Abel

Ah Yo demanding absolute allegiance to God, and Alice Akana flirting on the

fringes of paradise.

"You bet it will be a big telling, if Alice

ever begins," the beach-combing and disreputable kamaainas

(old-timers) gleefully told one another over their palm-tree gin.

In the clubs, the possibility of her telling was

of more moment. The younger generation of men announced that they had applied

for front seats at the telling, while many of the older generation of men joked

hollowly about the conversion of Alice. Further, Alice found herself abruptly

popular with friends who had forgotten her existence for twenty years.

One afternoon, as Alice, Bible in hand, was

taking the electric street-car at Hotel and Fort, Cyrus Hodge, sugar-factor

and magnate, ordered his chauffeur to stop beside her. Willy-nilly, in excess

of friendliness, he had her into his limousine beside him, and went

three-quarters of an hour out of his way and time personally to conduct her to

her destination.

"Good for sore eyes to see you," he

burbled. "How the years fly! You're looking fine. The secret of youth is

yours."

Alice smiled and complimented in return in the

royal Polynesian way of friendliness.

"My, my," Cyrus Hodge reminisced;

"I was such as boy in those days!"

"Some boy!" she laughed

acquiescence.

"But knowing no more than the foolishness of

a boy in those long-ago days."

"Remember the night your hack-driver got

drunk and left you ——"

"S-s-sh!" he cautioned. "That Jap

driver is a high-school graduate and knows more English than either of us.

Also, I think he is a spy for his government. So why should we tell him

anything? Besides, I was so very young. You remember ——"

"Your cheeks were like the peaches we used

to grow before the Mediterranean fruit-fly got into them," Alice agreed.

"I don't think you shaved more than once a week then. You were a pretty

boy. Don't you remember the hula we composed in your honor the ——"

"S-s-sh!" he hushed her. "All

that's buried and forgotten. May it remain forgotten!"

And she was aware that in his eyes was no longer

any of the ingenuousness of youth she remembered. Instead, his eyes were keen

and speculative, searching into her for some assurance that she would not

resurrect his particular portion of that buried past.

"Religion is a good thing for us as we get

along into middle age," another friend told her. He was building a

magnificent house on Pacific Heights, had but recently married a second time,

and was even then on his way to the steamer to welcome home his two daughters

just graduated from Vassar. "We need religion in our old age, Alice. It

softens, makes us more tolerant and forgiving of the weaknesses of

others—especially the weaknesses of youth of—of others, when they played high

and low and didn't know what they were doing."

He waited anxiously.

"Yes," she said; "we are all born

to sin, and it is hard to grow out of sin. But I grow—I grow."

"Don't forget, Alice, in those other days I

always played square. You and I never had a falling-out."

"Not even the night you gave that

luau when you were twenty-one and insisted on breaking the glassware

after every toast. But, of course, you paid for it."

"Handsomely," he asserted almost

pleadingly.

"Handsomely," she agreed. "I

replaced more than double the quantity with what you paid me, so that, at the

next luau, I catered one hundred and twenty plates without having to

rent or borrow a dish or glass. Lord Mainweather gave that luau—you

remember him?"

"I was pig-sticking with him at Mana,"

the other nodded. "We were at a two weeks' house-party there. But, say,

Alice, as you know, I think this religion stuff is all right and better than

all right. But don't let it carry you off your feet. And don't get to telling

your soul on me. What would my daughters think of that broken

glassware?"

"I always did have an aloha (warm

regard) "for you, Alice," a member of the Senate, fat and

bald-headed, assured her.

And another, a lawyer and a grandfather:

And another, a lawyer and a grandfather:

"We were always friends, Alice. And

remember, any legal advice or handling of business you may require, I'll do for

you gladly and without fees, for the sake of our old-time friendship."

Came a banker to her late Christmas eve, with

formidable, legal-looking envelops in his hand, which he presented to her.

"Quite by chance," he explained,

"when my people were looking up land records in Iapio Valley, I found a

mortgage of two thousand on your holdings there—that rice land leased to Ah

Chin. And my mind drifted back to the past when we were all young together—and

wild, a bit wild, to be sure. And my heart warmed with the memory of you, and,

so just as an aloha, here's the whole thing cleared off for

you."

Nor was Alice forgotten by her own people. Her

house became a Mecca for native men and women, usually performing pilgrimage

privily after darkness fell, with presents always in their hands—squid fresh

from the reef, opihis and limu, baskets of alligator-pears,

roasting-corn of the earliest from windward Oaho, mangoes and star-apples,

taro, pink and royal, of the finest selection, sucking pigs, banana,

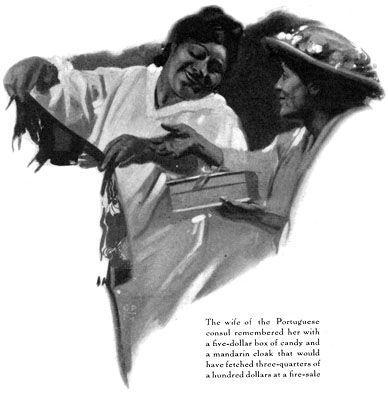

poi, breadfruit, and crabs caught the very day at Pearl Harbor. The wife

of the Portuguese consul remembered her with a five-dollar box of candy and a

mandarin cloak that would have fetched three-quarters of a hundred dollars at a

fire-sale. And Elvira Miyahara Makaena Yin Gap, the wife of Yin Gap, the

wealthy Chinese importer, brought personally to Alice two entire bots of

piña-cloth from the Philippines and a dozen pairs of silk

stockings.

The time passed, and Abel Ah Yo struggled with

Alice for a properly penitent heart, and Alice struggled with herself for her

soul, while half of Honolulu wickedly or apprehensively hung on the outcome.

Carnival-week was over; polo and the races had come and gone, and the

celebration of Fourth of July was ripening ere Abel Ah Yo beat down by brutal

psychology the citadel of her reluctance. It was then that he gave his famous

exhortation which might be summed up as Abel Ah Yo's definition of eternity. Of

course, like many another evangelist, Abel Ah Yo had cribbed the definition.

But no one in the Islands knew it, and his rating as a revivalist uprose a

hundred per cent.

So successful was his preaching that night that

he reconverted many of his converts, who fell and moaned about the penitent

form and crowded for room amongst scores of new converts burned by the

pentecostal fire, including half a company of negro soldiers from the

garrisoned Twenty-fifth Infantry, a dozen troopers from the Fourth Cavalry on

its way to the Philippines, as many drunken man-of-war's men, divers ladies

from Iwilei, and half the riffraff of the beach.

Abel Ah Yo, subtly sympathetic himself, by virtue

of his racial admixture, knowing human nature like a book and Alice Akana even

more so, knew just what he was doing when he arose that memorable night and

exposited God, hell, and eternity in terms of Alice Akana's comprehension. For,

quite by chance, he had discovered her cardinal weakness. First of all, like

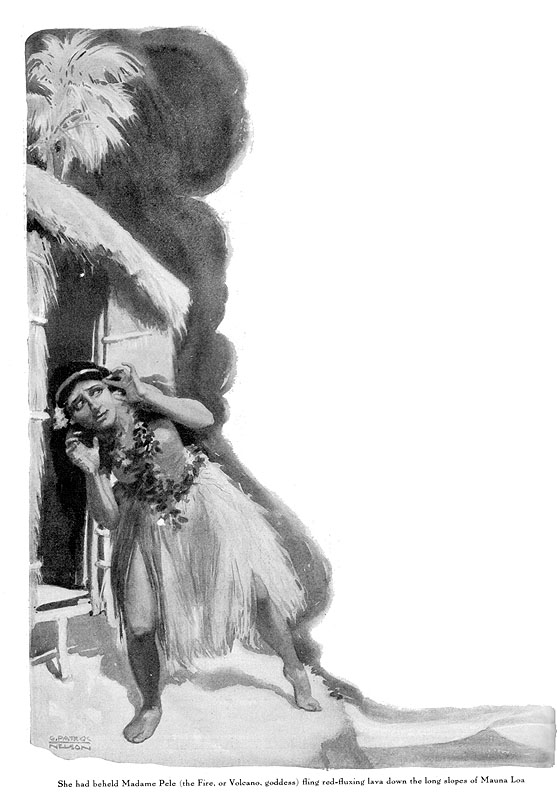

all Polynesians, an ardent lover of nature, he found that earthquake and

volcanic eruption were the things of which Alice lived in terror. She had been,

in the past, on the Big Island, through cataclysms that had shaken grass houses

down upon her while she slept, and she had beheld Madame Pele (the Fire, or

Volcano goddess) fling red-fluxing lava down the long slopes of Mauna Loa,

destroying fish-ponds on the sea-brim and licking up droves of beef cattle,

villages, and humans on her fiery way.

The night before, a slight earthquake had shaken

Honolulu and given Alice Akana insomnia. And the morning papers had stated that

Mauna Kea had broken into eruption, while the lava was rising rapidly in the

great pit of Kilauea. So, at the meeting, her mind vexed between the terrors of

this world and the delights of the eternal world to come, Alice sat down in a

front seat in a very definite state of the "jumps."

And Abel Ah Yo arose and put his finger on the

sorest part of her soul. Sketching the nature of God in the stereotyped way,

but making the stereotyped alive again with his gift of tongues in

pidgin-English and pidgin-Hawaiian, Abel Ah Yo described the day when the Lord,

even his infinite patience at an end, would tell Peter to close his day-book

and ledgers, command Gabriel to summon all souls to judgment, and cry out with

a voice of thunder, "Welakahao!"

And Abel Ah Yo arose and put his finger on the

sorest part of her soul. Sketching the nature of God in the stereotyped way,

but making the stereotyped alive again with his gift of tongues in

pidgin-English and pidgin-Hawaiian, Abel Ah Yo described the day when the Lord,

even his infinite patience at an end, would tell Peter to close his day-book

and ledgers, command Gabriel to summon all souls to judgment, and cry out with

a voice of thunder, "Welakahao!"

This anthropomorphic deity of Abel Ah Yo

thundering the modern Hawaiian-English slang of "Welakahao" at

the end of the world is a fair sample of the revivalist's speech-tools of

discourse. "Welakahao" means, literally, "hot iron."

It was coined in the Honolulu Iron Works by the hundreds of Hawaiian men there

employed, who meant by it "to hustle," "to get a move on,"

the iron being host meaning that the time had come to strike.

"And the Lord cried 'Welakahao,' and

the day of Judgment began and was over wikiwiki, (quickly) "just

like that; for Peter was a better bookkeeper than any in the Waterhouse Trust

Company, Limited, and, further, Peter's books were true."

Swiftly Abel Ah Yo divided the sheep from the

goats and hastened the latter down into hell.

"And now," he demanded, perforce his

language on these pages being properly Englished, "what is hell like? Oh,

my friends, let me describe to you, in a little way, what I have beheld with my

own eyes on earth of the possibilities of hell. I was a young man, a boy, and I

was at Hilo. Morning began with earthquake. Throughout the day, the mighty land

continued to shake and tremble till strong men became seasick, and women clung

to the trees to escape falling, and cattle were thrown down off their feet. I

beheld myself a young calf so thrown. A night of terror indescribable followed.

The land was in motion like a canoe in a kona gale. There was an infant

crushed to death by its fond mother stepping upon it whilst fleeing her falling

house.

"The heavens were on fire above us. We read

our Bibles by the light of th heavens, and the print was fine even for young

eyes. Those missionary Bibles were always too small of print. Forty miles away

from us, the heart of hell burst from the lofty mountains and gushed red blood

of fire-melted rock toward the sea. With the heavens in vast conflagration and

the earth hulaing beneath our feet, was a scene too awful and too

majestic to be enjoyed. We could think only of the thin bubble-skin of earth

between us and the everlasting lake of fire and brimstone, and of God, to whom

we prayed to save us. There were earnest and devout souls who there and then

promised their pastors to give not their shaved tithes but five-tenths of their

all to the Church, if only the Lord would let them live to contribute.

"Oh, my friends, God saved us! But first he

showed us a foretaste of that hell that will yawn for us on the last day when

he cries, 'Welakahao!' in a voice of thunder. 'When the iron is hot!'

Think of it! When the iron is hot for sinners!

"By the third day, things being much

quieter, my friend the preacher and I, being calm in the hand of God,

journeyed up Mauna Loa and gazed into the awful pit of Kilauea. We gazed down

into the fathomless abyss to the lake of fire far below, roaring and dashing,

its fiery spray into billows and fountaining hundreds of feet into the air like

Fourth-of-July fireworks you have all seen, and all the while we were

suffocating and made dizzy by the immense volumes of smoke and brimstone

ascending.

"And I say unto you, no pious person could

gaze down upon that scene without recognizing full the Bible picture of the pit

of hell. Believe me, the writers of the New Testament had nothing on us. As for

me, my eyes were fixed upon the exhibition before me, and I stood mute and

trembling under a sense never before so fully realized of the power of Almighty

God—the resources of his wrath, and the untold horror of the finally

impenitent who do not tell their souls and make their peace with the

Creator.

"But, oh, my friends, think you our guides,

our native attendants, deep-sunk in heathenism, were affected by such a scene?

No. The devil's hand was upon them. Utterly regardless and unimpressed, they

were only careful about their supper, chatted about their raw fish, and

stretched themselves upon their mats to sleep. Children of the devil they were,

insensible to the beauties, the sublimities, and the awful terror of God's

works. But you are no heathen I now address. What is a heathen? He is one who

betrays a stupid insensibility to every elevated idea and to every elevated

emotion. If you wish to awaken his attention, do not bid him to look down into

the pit of hell. But present him with a calabash of poi, a raw fish, or

invite him to some low, groveling, and sensuous sport. Oh, my friends, how lost

are they to all that elevates the immortal soul! But the preacher and I, sad

and sick of heart for them, gazed down into hell. Oh, my friends, it was

hell, the hell of the Scriptures, the hell of eternal torment for the

undeserving—"

Alice Akana was in an ecstasy or hysteria of

terror. She was mumbling incoherently:

"O Lord, I will give nine-tenths of my all!

I will give all even the two bolts of piña-cloth, the mandarin

cloak, and the entire dozen silk stockings ——"

By the time she could lend ear again, Abel Ah Yo

was launching out on his famous definition of eternity.

"Eternity is a long time, my friends. God

lives, and, therefore, God lives inside eternity. And God is very old. The

fires of hell are as old and as everlasting as God. How else could there be

everlasting torment for those sinners cast down by God into the pit on the last

day to burn forever and forever through all eternity? Oh, my friends, your

minds are small—too small to grasp eternity! Yet is it given to me, by God's

grace, to convey to you an understanding of a tiny bit of eternity.

"The grains of sand on the beach of Waikiki

are as many as the stars, and more. No man may count them. Did he have a

millions lives in which to count them, he would have to ask for more time. Now

let us consider a little dinky old minah-bird with one broken wing, that cannot

fly. At Waikiki the minah-bird that cannot fly takes one grain of sand in its

beak and hops, hops, all day long and for many days, all the way to Pearl

Harbor and drops that one grain of sand into the harbor. Then it hops, hops,

all day and for many days, all the way back to Waikiki for another grain of

sand. And again it hops, hops all the way back to Pearl Harbor. And it

continues to do this through the years and centuries and the thousands and

thousands of centuries until, at last, there remains not one grain of sand at

Waikiki, and Pearl Harbor is filled up with land and growing coconuts and

pine-apples. And then, O my friends, even then, IT WOULD NOT YET BE SUNRISE IN

HELL!"

Here, at the smashing impact of so abrupt a

climax, unable to withstand the sheer simplicity and objectivity of such artful

measurement of a trifle of eternity, Alice Akana's mind broke down and blew up.

She uprose, reeled blindly, and stumbled to her knees at the penitent form.

Abel Ah Yo had not finished his preaching, but it was his give to know

crowd-psychology and to feel the heat of the pentecostal conflagration that

scorched the audience. He called for a rousing revival hymn from his singers,

and stepped down to wade among the hallelujah-shouting negro soldiers to Alice

Akana. And, ere the excitement began to ebb, nine-tenths of his congregation

and all his converts were down on knees and praying and shouting aloud an

immensity of contriteness and sin.

Word came, via telephone, almost simultaneously

to the Pacific and University Clubs, that, at last, Alice was telling her soul

in meeting; and, by private machine and taxi-cab, for the first time Abel Ah

Yo's revival was invaded by those of caste and place. The first comers beheld

the curious sight of Hawaiian, Chinese, and all variegated racial mixtures of

the melting-pot of Hawaiian men and women fading out and slinking away through

the exits of Abel Ah Yo's tabernacle. But those who were sneaking out were

mostly men, while those who remained were avid-faced as they hung on Alice's

utterances.

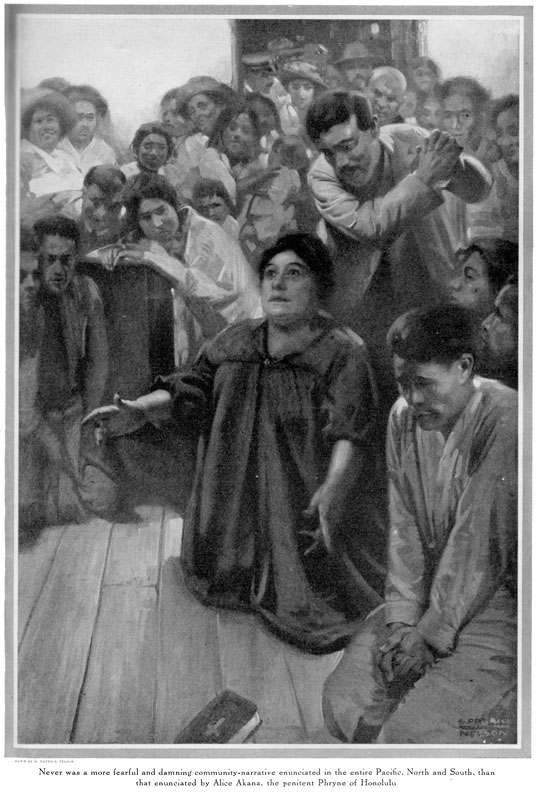

Never was a more fearful and damning

community-narrative enunciated in the entire Pacific, North and South, than

that enunciated by Alice Akana, the penitent Phryne of Honolulu.

"Huh!" the first comers heard her

saying, having already disposed of most of the venial sins of the lesser ones

of her memory. "You think this man, Stephen Makekau, is the son of Moses

Makekau and Minnie Ah Ling, and has a legal right to the two hundred and eight

dollars he draws each month from Parke Richards, Limited, for the lease of the

fish-pond to Bill Kong at Amana. Not so. Stephen Makekau is not the son of

Moses. He is the son of Aaron Kama and Tillie Naone. He was given as a present,

as a feeding child, to Moses and Minnie by Aaron and Tillie. I know. Moses and

Minnie and Aaron and Tillie are dead. Yet I know and can prove it. Old Mrs.

Poepoe is still alive. I was present when Stephen was born, and in the

night-time, when he was two months old, I myself carried him as a present to

Moses and Minnie, and old Mrs. Poepoe carried the lantern. This secret has been

one of my sins. It has kept me from God. Now I am free of it. Young Archie

Makekau, who collects bills for the gas company and plays baseball in the

afternoons and drinks too much gin, should get that two hundred and eight

dollars the first of each month from Parke Richards, Limited. He will blow it

in on gin and an automobile. Stephen is a good man. Archie is no good. Also he

is a liar, and he has served two sentences on the reef. Yet God demands the

truth, and Archie will get the money and make a bad use of it."

And, in such fashion, Alice rambled on through

the experiences of her long and full-packed life. And women forgot they were inu

the tabernacle, and men, too; and faces darkened with passion as they learned,

for the first time, the long-buried secrets of their other halves.

"The lawyers' offices will be crowded

to-morrow morning," MacIlwaine, chief of detectives, muttered in Colonel

Stilton's ear.

Colonel Stilton grinned affirmation, although the

chief of detectives could not fail to note the ghastliness of the grin.

"There is a banker in Honolulu. You all know

his name. He is 'way up, swell society because of his wife. He owns much stock

in General Plantations & Inter-Island. His name is Colonel Stilton. Last

Christmas eve he came to my house with big aloha" (love) "and

gave me mortgages on my land in Iapio Valley, all canceled, for two thousand

dollars' worth. Now why did he have such big cash aloha for me? I will

tell you—" And tell she did, throwing the search-light on ancient

business transactions which, from their inception, had lurked in the dark.

"This," Alice concluded the episode,

"has long been a sin upon my conscience and kept my heart from God.

"And Harold Miles was that time president of

the Senate, and next week he bought three town lots at Pearl Harbor, and

painted his Honolulu house, and paid up his back dues in his clubs. Also the

Ramsay home at Honokiki was left by will to the people if the government would

keep it up. But if the government, after two years, did not begin to keep it

up, then would it go to the Ramsay heirs who old Ramsay hated like poison.

Well, it went to the heirs all right. Their lawyer was Charlie Middleton, and

he had me help fix it with the government men. And their names were:" Six

names, from both branches of the legislature, Alice recited, and added:

"Maybe they all painted their houses after that. For the first time have I

spoken. My heart is much lighter and softer. It has been coated with an armor

of house-paint against the Lord. And there is Harry Werther. He was in the

Senate that time. Everybody said bad things about him, and he was never

reelected. Yet his house was not painted. He was honest. To this day, his house

is not painted, as everybody knows.

"There is Jim Lokendamper. He has a bad

heart. I heard him, only last week, right here before you all, tell his soul.

He did not tell all his soul, and he lied to God. I am not lying to God. It is

a big telling, but I am telling everything. Now Azalea Akau, sitting right over

there, is his wife. But Lizzie Lokendamper is his married wife. A long time ago

he had the great aloha for Azalea. You think her uncle who went to

California and died left her by will that two thousand five hundred dollars she

got. Her uncle did not. I know. Her uncle died broke in California, and Jim

Lokendamper sent eighty dollars to California to bury him. Jim Lokendamper had

a piece of land in Kohala he got from his mother's aunt. Lizzie, his married

wife, did not know this. So he sold it to the Kohala Ditch Company and gave the

twenty-five hundred to Azalea Akau ——"

Here, Lizzie, the married wife, upstood like a

fury long-thwarted, and, in lieu of her husband, already fled, flung herself

tooth and nail on Azalea.

"Wait, Lizzie Lokendamper!" Alice cried

out. ":I have much weight of you on my heart, and some house-paint,

too—" And when she had finished her disclosure of how Lizzie had painted

her house, Azalea was up and raging.

"Wait, Azalea Akau! I shall now lighten my

heart about you. And it is not house-paint. Jim always paid that. It is your

new bathtub and modern plumbing that is heavy on me—"

Worse, much worse, about many and sundry, did

Alice Akana have to say, cutting high in business, financial, and social life,

as well as low. None was too high or too low to escape; and not until two in

the morning, before an entranced audience that packed the tabernacle to the

doors, did she complete her recital of the personal and detailed iniquities she

knew of the community. Just as she was finishing, she remembered more.

"Huh!" she sniffed. "I gave last

week one lot worth eight hundred dollars cash market price to Abel Ah Yo to pay

running-expenses and add up in Peter's account-books in heaven. Where did I get

that lot? You all think Mr. Fleming Jason is a good man. He is more crooked

than the entrance was to Pearl Lochs before the United States government

straightened the channel. He has liver-disease now, but his sickness is a

judgment of God, and he will die crooked. Mr. Fleming Jason gave me that lot

twenty-two years ago when its cash market price was thirty-five dollars.

Because his aloha for me was big? No. He never had aloha inside

of him except for dollars.

"You listen. Mr. Fleming Jason put a great

sin upon me. When Frank Lomiloli was at my house, full of gin, for which gin

Mr. Fleming Jason paid me in advance five times over, I got Frank Lomiloli to

sign his name to the sale-paper of his town land for one hundred dollars. It

was worth six hundred then. It is worth twenty thousand now. Maybe you want to

know where that town land is. I will tell you, and remove it off my heart. It

is on King Street, where is now the Come Again Saloon, the Japanese Taxi-cab

Company garage, the Smith & Wilson plumbing shop, and the Ambrosia

Ice-Cream Parlors, with the two more stories big Addison Longing-House

overhead. And it is all wood, and always has been well painted. Yesterday they

started painting it again. But that paint will not stand between me and God.

There are no more paint-pots between me and my path to heaven."

The morning and evening papers of the day

following held an unholy hush on the greatest news-story of years; but Honolulu

was half agiggle and half aghast at the whispered reports, not always basely

exaggerated, that circulated wherever two Honolulans chanced to meet.

"Our mistake," said Colonel Stilton, at

the club, "was that we did not, at the very first, appoint a committee of

safety to keep track of Alice's soul."

Bob Cristy, one of the younger Islanders, burst

into laughter so pointed and so loud that the meaning of it was demanded.

"Oh, nothing much," was his reply.

"But I heard, on my way here, that old John Ward had just been run in for

drunken and disorderly conduct and for resisting an officer. Now Abel Ah Yo

fine-tooth-combs the police court. He loves nothing better than soul-snatching

a chronic drunkard."

Colonel Stilton looked at Lask Finneston, and

both looked at Gary Wilkinson. He returned to them a similar look.

"The old beach-comber!" Lask Finneston

cried. "The drunken old reprobate! I'd forgotten he was alive. Wonderful

constitution. Never drew a sober breath except when he was shipwrecked, and,

when I remember him, into every deviltry afloat. He must be going on

eighty."

"He isn't far way from it," Bob Cristy

nodded. "Still beach-combs, drinks when he gets the price, and keeps all

his senses, though he's not spry and has to use glasses when he reads. And his

memory is perfect. Now, if Abel Ah Yo catches him—"

Gary Wilkinson cleared his throat, preliminary to

speech.

"Now, there's a grand old man" he said.

"A left-over from a forgotten age. Few of his type remains. A pioneer. A

true kamaaina" (old-timer). "Helpless and in the hands of the

police in his old age. We should do something for him in recognition of his

yeoman work in Hawaii. His old home, I happen to know, is Sag Harbor. He hasn't

seen it for over half a century. Now, why shouldn't he be surprised to-morrow

morning by having his fine paid and by being presented with return-tickets to

Sag Harbor, and, say, expenses for a year's trip? I move a committee. I appoint

Colonel Stilton, Lask Finneston, and myself. As for chairman, who more

appropriate than Lask Finneston, who knew the old gentleman so well in the

early days? Since there is no objection, I hereby appoint Lask Finneston

chairman of the committee for the purpose of raising and donating money to pay

the police-court fine and the expenses of a year's travel for that noble

pioneer, John Ward, in recognition of a lifetime of devotion of energy to the

upbuilding of Hawaii."

There was no dissent.

"The committee will now go into secret

session," said Lask Finneston, arising and indicating the way to the

library.

From the March 1918 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.