Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

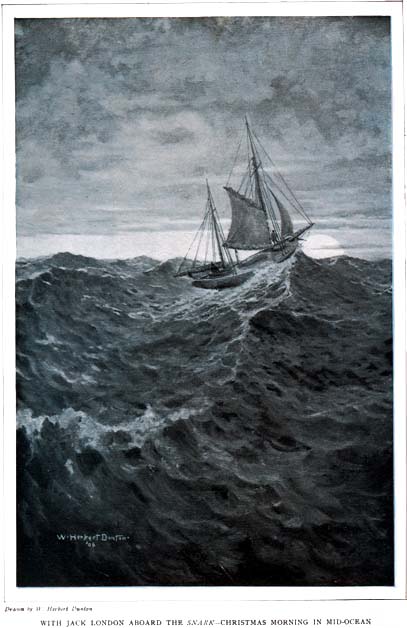

Jack London is off on his round-the-world

voyage for the Cosmopolitan, in his little forty-five-foot, ketch-rigged boat,

the Snark, with Mrs. London, her uncle, a cook, and a Japanese

cabin-boy. The author of "The Sea Wolf" expects to be gone several

years and, for the time, to do all his writing on board his boat. He will write

the story of the voyage exclusively for the Cosmopolitan, and expects to begin

his narration in the January or February number.

Here is a characteristic foreword from Mr.

London, in which he tells about his little craft and the proposed voyage. -

Editor's Note.

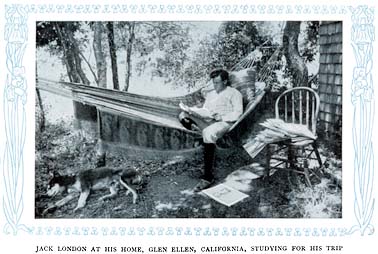

T began in the swimming-pool at Glen Ellen. Between

swims it was our wont to come out and lie in the sand and let our skins breathe

the warm air and soak in the sunshine. Roscoe, who is Charmian's uncle, was a

yachtsman. I had followed the sea a bit. It was inevitable that we should talk

about boats. We talked about small boats and the seaworthiness of small boats.

We asserted that we were not afraid to go around the world in a small boat,

say, forty feet long. We asserted finally that there was nothing in this world

we would like better than a chance to do it.

T began in the swimming-pool at Glen Ellen. Between

swims it was our wont to come out and lie in the sand and let our skins breathe

the warm air and soak in the sunshine. Roscoe, who is Charmian's uncle, was a

yachtsman. I had followed the sea a bit. It was inevitable that we should talk

about boats. We talked about small boats and the seaworthiness of small boats.

We asserted that we were not afraid to go around the world in a small boat,

say, forty feet long. We asserted finally that there was nothing in this world

we would like better than a chance to do it.

"Let us do it," we said - in fun.

Then I asked Charmian on the side if she would

really care to do it, and she said that it was too good to be true.

The next time we breathed our skins in the sand

by the swimming-pool, I said to Roscoe,

"Let us do it."

I was in earnest and so was he, for he said,

"When shall we start?"

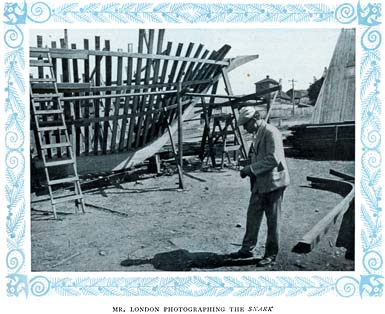

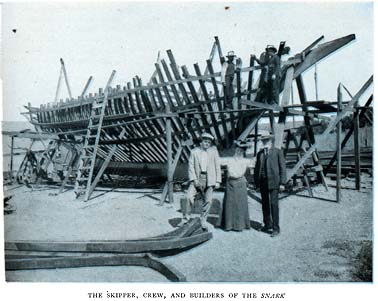

So the trip was decided upon, and the building

of the Snark began at once.

Our friends cannot understand why we make this

voyage. They shudder and moan and raise their hands. No amount of explanation

can make them comprehend that we are moving along the line of least resistance;

that it is easier for us to go down to the sea in a small ship than to remain

on dry land, just as it is easier for them to remain on dry land than to go

down to the sea in a small ship. This state of mind comes of an undue

prominence of the ego. They cannot get away from themselves. They cannot come

out of themselves long enough to see that their line of least resistance is not

necessarily everybody else's line of least resistance. They make of their own

bundle of desires, likes, and dislikes a yardstick wherewith to measure the

desires, likes, and dislikes of all creatures. This is unfair. I tell them so;

but they cannot get away from their own miserable egos long enough to hear me.

They think I am crazy. In return, I am sympathetic. We are all prone to think

there is something wrong with the mental processes of the man who disagrees

with us.

that it is easier for us to go down to the sea in a small ship than to remain

on dry land, just as it is easier for them to remain on dry land than to go

down to the sea in a small ship. This state of mind comes of an undue

prominence of the ego. They cannot get away from themselves. They cannot come

out of themselves long enough to see that their line of least resistance is not

necessarily everybody else's line of least resistance. They make of their own

bundle of desires, likes, and dislikes a yardstick wherewith to measure the

desires, likes, and dislikes of all creatures. This is unfair. I tell them so;

but they cannot get away from their own miserable egos long enough to hear me.

They think I am crazy. In return, I am sympathetic. We are all prone to think

there is something wrong with the mental processes of the man who disagrees

with us.

But to return to the Snark, and why I, for

one, want to journey in her around the world. The things I like constitute my

set of values. The thing I like most of all is personal achievement - not

achievement for the world's applause, but achievement for my own delight. It is

the old "I did it! I did it! With my own hands I did it!" But

personal achievement, with me, must be concrete. I would rather win a

water-fight in the swimming-pool, or remain astride a horse that is trying to

get out from under me, than write the great American novel. Some other fellow

would prefer writing the great American novel to winning the water-fight or

mastering the horse.

Possibly the proudest achievement of my life, my

moment of highest living, occurred when I was seventeen. I was in a

three-masted schooner off the coast of Japan. We were in a typhoon. All hands

had been on deck most of the night. I was called from my bunk at seven in the

morning to take the wheel. Not a stitch of canvas was set. We were running

before the storm under the bare poles, yet the schooner fairly tore along. The

seas were all of an eighth of a mile apart, and the wind snatched the whitecaps

from their summits, filling the air so thick with driving spray that it was

impossible to see more than two waves at a time. The schooner was almost

unmanageable, rolling her rail under to starboard and to port, veering and

yawing anywhere between southeast and southwest, and threatening, when the

huge seas lifted under her quarter, to broach to. Had she broached to, she

would ultimately have been reported lost with all hands and no tidings.

I took the wheel. The sailing-master watched me

for a space. He was afraid of my youth, afraid that I lacked the strength; but

when he saw me successfully wrestle the schooner through several bouts, he went

below to breakfast. Fore and aft, all hands were below at breakfast. Had she

broached to, not one of them would ever have reached the deck. For forty

minutes I stood there alone at the wheel, in my grasp the wildly careering

schooner and the lives of twenty-two men. Once we were pooped. I saw it coming,

and, half-drowned, with tons of water crushing me, I checked the schooner's

rush to broach to. At the end of the hour, sweating and played out, I was

relieved. But I had done it! With my own hands I had done my trick at the

wheel, driving a hundred tons of wood and iron through a few million tons of

foam-capped waves.

My delight was in that I had done it, not in the

fact that twenty-two men knew I had done it. Within the year over half of them

were dead and gone, and yet my pride in the thing performed was not diminished

by half. I am willing to confess, however, that I do like a small audience. But

it must be a very small audience, composed of those who love me and whom I

love. When I then accomplish personal achievement I have a feeling that I am

justifying their love for me; but this is quite apart from the delight of the

achievement itself. This delight is peculiarly my own and does not depend on

witnesses. When I have done some such thing, I am exalted. I glow all over. I

am aware of a pride in myself that is mine and mine alone. It is organic; every

fiber of me is thrilling with it. It is very natural. It is a mere matter of

satisfaction at adjustment to environment. It is success.

Life that lives is life successful, and success

is the breath in its nostrils. The achievement of a difficult feat is

successful adjustment to a sternly exacting environment The

more difficult the feat, the greater the satisfaction at its accomplishment.

That is why I am building the Snark. I am so made. The trip around the

world means big moments of living.

Bear with me a moment and look at it. Here am I, a little animal called a man -

a bit of vitalized matter, one hundred and sixty-five pounds of meat, blood,

nerve, sinew, bones, and brain, all of it soft and tender, susceptible to hurt,

fallible and frail. I strike a light backhanded blow on the nose of an

obstreperous horse and a bone in my hand is broken. I put my head under the

water for five minutes and I am drowned. I fall twenty feet through the air and

I am smashed. I am a creature of temperature. A few degrees one way and my

fingers and ears and toes blacken and drop off. A few degrees the other way and

my skin blisters and shrivels away from the raw, quivering flesh. A few

additional degrees either way and the life and the light in me go out. A drop

of poison injected into my body from a snake and I cease to move - forever I

cease to move. A splinter of lead from a rifle enters my head and I am wrapped

around in the eternal blackness wherein I am not.

Bear with me a moment and look at it. Here am I, a little animal called a man -

a bit of vitalized matter, one hundred and sixty-five pounds of meat, blood,

nerve, sinew, bones, and brain, all of it soft and tender, susceptible to hurt,

fallible and frail. I strike a light backhanded blow on the nose of an

obstreperous horse and a bone in my hand is broken. I put my head under the

water for five minutes and I am drowned. I fall twenty feet through the air and

I am smashed. I am a creature of temperature. A few degrees one way and my

fingers and ears and toes blacken and drop off. A few degrees the other way and

my skin blisters and shrivels away from the raw, quivering flesh. A few

additional degrees either way and the life and the light in me go out. A drop

of poison injected into my body from a snake and I cease to move - forever I

cease to move. A splinter of lead from a rifle enters my head and I am wrapped

around in the eternal blackness wherein I am not.

Fallible and frail, a bit of pulsating,

jelly-like life - it is all I am. About me are the great natural forces -

colossal menaces, Titans of destruction, unsentimental monsters that have less

concern for me than I have for the grain of sand I crush under my foot; they do

not know me. They are unconscious, unmerciful, and unmoral. They are the

cyclones and tornadoes, lightning flashes and cloudbursts, tide-rips and tidal

waves, undertows and waterspouts, great whirls and sucks and eddies,

earthquakes and volcanoes, surfs that thunder on rock-ribbed coasts and seas

that leap aboard the largest craft that float, crushing humans to pulp or

licking them off into the sea and to death - and these insensate monsters do

not know that tiny, sensitive creature, all nerves and weaknesses, whom men

call Jack London and who thinks he is all right and quite a superior being. And

in the maze and chaos of the conflict of these vast and draughty Titans, it is

for me to thread my precarious way. The bit of life that is I will exult over

them. The bit of life that is I, in so far as it succeeds in baffling them or

in bitting them to its services, will imagine that it is godlike. I dare assert

that for a finite speck of pulsating jelly to feel godlike is a far more

glorious feeling than for a god to feel godlike.

Here is the sea, the wind, and the wave. Here are

the seas, the winds, and the waves of all the world. Here is a ferocious

environment. And here is difficult adjustment, the achievement of which is

delight to the small quivering vanity that is I. I like it. I am so made. It is

my own particular form of vanity, that is all.

There is also another side to the voyage of the

Snark. Being alive, I want to see, and the world is a bigger thing to

see than one small town or valley. We have done little outlining of the voyage.

Only one thing is definite, and that is that our first port of call will be

Hawaii. Beyond a few general ideas, we have no thought of our next port after

Hawaii. We shall make up our minds as we get nearer. In a general way we know

that we shall wander through the South Seas, take in Samoa, New Zealand,

Tasmania, Australia, New Guinea, Borneo, and Sumatra, and go on up through the

Philippines to Japan. Then will come Korea, China, India, the Red Sea, and the

Mediterranean. After that the voyage becomes too vague to describe, though we

know a number a things we shall surely do, and we expect to spend

from one to several months in every country in Europe.

There is also another side to the voyage of the

Snark. Being alive, I want to see, and the world is a bigger thing to

see than one small town or valley. We have done little outlining of the voyage.

Only one thing is definite, and that is that our first port of call will be

Hawaii. Beyond a few general ideas, we have no thought of our next port after

Hawaii. We shall make up our minds as we get nearer. In a general way we know

that we shall wander through the South Seas, take in Samoa, New Zealand,

Tasmania, Australia, New Guinea, Borneo, and Sumatra, and go on up through the

Philippines to Japan. Then will come Korea, China, India, the Red Sea, and the

Mediterranean. After that the voyage becomes too vague to describe, though we

know a number a things we shall surely do, and we expect to spend

from one to several months in every country in Europe.

The Snark is to be sailed. There will be a

gasoline engine on board, but it will be used only in case of emergency, such

as in bad water among reefs and shoals, where a sudden calm in a swift current

leaves a sailing-boat helpless. The rig of the Snark is to be what is

called the ketch. The ketch-rig is a compromise between the yawl and the

schooner. Of late years, the yawl-rig has proved the best for cruising. The

ketch retains the cruising virtues of the yawl, and in addition manages to

embrace a few of the sailing virtues of the schooner. The foregoing must be

taken with a pinch of salt; it is all theory in my head. I have never sailed a

ketch, nor even seen one, but the theory commends itself to me. Wait till I get

out on the ocean, then I shall be able to tell more about the cruising and

sailing qualities of the ketch.

There will be no crew; or rather Charmian,

Roscoe, and I will be the crew. We are going to do the thing with our own

hands. With our own hands we are going to circumnavigate the globe. Sail her or

sink her, with our own hands we will do it. Of course, there will be a cook and

a cabin-boy. Why should we stew over a stove, wash dishes, and set the table?

We could stay on land if we wanted to do those things. Besides, we shall have

to stand watch and work the ship. And I shall have to work at my trade of

writing in order to feed us and to get new sails and tackle and keep the

Snark in efficient working order. And then there is the ranch; I've got

to keep the vineyard, orchard, and hedges going.

As originally planned, the Snark was to be

forty feet long on the water-line; but we discovered there was no space for a

bathroom, and for that reason we have increased her length to forty-five feet.

Her greatest beam is fifteen feet. She has no house and no hold. There is six

feed of headroom, and the deck is unbroken save for two companionways and a

hatch for'ard. The fact that there is no house to break the strength of the

deck will make us feel safer in case great seas thunder their tons of water

down on board. A small but convenient cock-pit, sunk beneath the deck, with

high rail and self-bailing, will make our rough-weather days and nights more

comfortable.

When we increased the length of the Snark

in order to get space for a bathroom, we found that all the space was not

required for that purpose. Because of this we increased the size of the engine.

Seventy horse-power our engine is, and since we expect it to drive us along at

a nine-knot clip, we do not know the name of a river with a current swift

enough to defy us.

We expect to do a lot of inland work. The

smallness of the Snark makes this possible. When we enter the land, out

go the masts and on goes the engine. There are the canals of China, and the

Yang-tse River. We shall spend months on them if we can get permission from the

government. That will be the one obstacle to our inland voyaging - governmental

permission. But if we can get that permission, there is scarcely a limit to the

inland voyaging we can do. When we come to the Nile, why, we can go up the

Nile. We can go up the Danube to Vienna, up the Thames to London, and we can go

up the Seine to Paris and moor opposite the Latin Quarter, with a bow-line out

to Notre Dame and a stern-line to the Morgue. We can leave the Mediterranean

and go up the Rhone to Lyons, there enter the Saône, cross from the

Saône to the Marne through the Canal de Bourgogne, from the Marne enter

the Seine, and go out the Seine at Havre. When we cross the Atlantic to the

United States, we can go up the Hudson, pass through the Erie Canal, cross the

Great Lakes, leave Lake Michigan at Chicago, gain the Mississippi by way of the

Illinois River and the connecting canal, and go down the Mississippi to the

Gulf of Mexico. And from there are the great rivers of South America. We shall

know something about geography when we get back to California.

People who build houses are often sore perplexed;

but if they enjoy the strain of it, I advise them to build a boat like the

Snark. Just consider for a moment the strain of detail. Take the engine.

What is the best kind of engine - the two-cylinder? three-cylinder?

four-cylinder? My lips are mutilated with all kinds of strange jargon, my mind

is mutilated with still stranger ideas and is weary from traveling in new and

rocky realms of thought. Ignition methods - shall it be make-and-break or jump

spark? Shall dry cells or storage-batteries be used? A storage-battery commends

itself, but it requires a dynamo. How powerful a dynamo? And when we have

installed a dynamo and a storage-battery, it is simply ridiculous not to light

the boat with electricity. Then comes the discussion of how many lights and how

many candle-power. It is a splendid idea. But electric lights will demand a

more powerful storage-battery, which, in turn, demands a more powerful dynamo.

And now that we have gone for it, why not have a search-light? It would be

tremendously useful. But the search-light needs so much electricity that when

it is used it will put all the other lights out of commission. Again we travel

the weary road in the quest after more power for storage-battery and dynamo.

And the, when it is finally solved, some one asks, "What if the engine

breaks down?" and we collapse. There are the side-lights, the

binnacle-light, and the anchor-light. Our very lives depend on them; so we have

to fit the boat throughout with oil lamps as well.

installed a dynamo and a storage-battery, it is simply ridiculous not to light

the boat with electricity. Then comes the discussion of how many lights and how

many candle-power. It is a splendid idea. But electric lights will demand a

more powerful storage-battery, which, in turn, demands a more powerful dynamo.

And now that we have gone for it, why not have a search-light? It would be

tremendously useful. But the search-light needs so much electricity that when

it is used it will put all the other lights out of commission. Again we travel

the weary road in the quest after more power for storage-battery and dynamo.

And the, when it is finally solved, some one asks, "What if the engine

breaks down?" and we collapse. There are the side-lights, the

binnacle-light, and the anchor-light. Our very lives depend on them; so we have

to fit the boat throughout with oil lamps as well.

But we are not done with that engine yet. The

engine is powerful. We are two small men and a small woman. It will break our

hearts and our backs to hoist anchor by hand. Let the engine do it. And then

comes the problem of how to convey power for'ard from the engine to the winch.

And by the time all this is settled, we redistribute the allotments of space to

the engine-room, galley, bathroom, staterooms, and cabin, and begin all over

again. And when we have shifted the engine I send off a telegram of gibberish

to its makers at New York, something like this: "Toggle-joint abandoned

change thrust-bearing accordingly distance from forward side of fly-wheel to

face of stern-post sixteen feet six inches."

Just potter around in quest of the best

steering-gear, or try to decide whether you sill set up your rigging with

old-fashioned lanyards or with turnbuckles, if you want strain of detail. Shall

the binnacle be located in front of the wheel in the center of the beam? or

shall it be located to one side in front of the wheel? There is room for a

library of sea-dog controversy. Then there is the problem of gasoline, fifteen

hundred gallons of it. What are the safest ways to tank it and to pipe it? and

which is the best fire-extinguisher for a gasoline fire? Then there is the

pretty problem of the life-boat and the storage of same. And when that is

finished, come the cook and cabin-boy to confront one with nightmare

possibilities. It is a small boat, and we will be packed close together. The

servant-girl problem of landsmen pales to insignificance. We did select one

cabin-boy and by that much were our troubles eased. And then the cabin-boy fell

in love and resigned.

And in the meantime how is one to find time to

study navigation when he is divided between those problems and the earning of

the money wherewith to settle the problems? Neither Roscoe nor I knows

anything about navigation, and the summer is gone, and we are about to start,

and the problems are thicker than ever, and the treasure is stuffed with

emptiness. Well, anyway, it takes years to learn seamanship, and both of us are

seamen. If we don't find the time, we'll lay in the books and instruments and

teach ourselves navigation on the ocean between San Francisco and Hawaii.

There is one unfortunate and perplexing phase of

the voyage of the Snark. Roscoe, who is to be my co-navigator, believes

that the surface of the earth is concave, and that we live in the inside of a

hollow sphere. Thus, though we shall sail on the one boat, the Snark,

Roscoe will journey around the world on the inside while I shall journey around

on the outside. But of this, more anon. We threaten to be of one mind before

the voyage is completed. I am confident that I shall convert him into making

the journey on the outside, while he is equally confident that before we arrive

back in San Francisco I shall be on the inside of the earth. How he is going

to get me through the crust I don't know, but Roscoe is aye a masterful man.

P.S. - That engine! While we've got it and the dynamo and storage-battery, why not have an ice-machine? Ice in the tropics! It is more necessary than bread. Here goes for the ice-machine! Now I am plunged into chemistry, and my lips hurt, and my mind hurts, and how am I ever to find the time to study navigation?

From the December, 1906 issue of Cosmopolitan Magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.