Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

|

Illustrated by G. Patrick Nelson |

![]() HERE it was!

The abrupt liberation of sound, as he timed it with his watch, Bassett likened

to the trump of an archangel. Walls of cities, he meditated, might well fall

down before so vast and compelling a summons. For the thousandth time vainly,

he tried to analyze the tone-quality of that enormous peal that dominated the

land far into the strongholds of the surrounding tribes. The mountain gorge,

which was its source, rang to the rising tide of it until it brimmed over and

flooded earth and sky and air. With the wantonness of a sick man's fancy, he

likened it to the mighty cry of some Titan of the Elder World vexed with misery

or wrath. Higher and higher it rose, challenging and demanding in such profound

of volume that it seemed intended for ears beyond the narrow confines of the

solar system.

HERE it was!

The abrupt liberation of sound, as he timed it with his watch, Bassett likened

to the trump of an archangel. Walls of cities, he meditated, might well fall

down before so vast and compelling a summons. For the thousandth time vainly,

he tried to analyze the tone-quality of that enormous peal that dominated the

land far into the strongholds of the surrounding tribes. The mountain gorge,

which was its source, rang to the rising tide of it until it brimmed over and

flooded earth and sky and air. With the wantonness of a sick man's fancy, he

likened it to the mighty cry of some Titan of the Elder World vexed with misery

or wrath. Higher and higher it rose, challenging and demanding in such profound

of volume that it seemed intended for ears beyond the narrow confines of the

solar system.

Such the sick man's fancy. Still he drove to

analyze the sound. Sonorous as thunder was it, mellow as a golden bell, thin

and sweet as a thrummed taut cord of silver—no; it was none of these, or

a blend of these. There were no words or semblances in his vocabulary and

experience with which to describe the totality of that sound.

Time passed. Minutes merged into quarters of

hours, and quarters of hours into half-hours, and still the sound persisted,

ever changing from its initial vocal impulse, yet never receiving fresh

impulse—fading, dimming, dying as enormously as it has sprung into being.

It became a confusion of troubled mutterings and babblings and colossal

whisperings. Slowly it withdrew, sob by sob, into whatever great bosom had

birthed it, until it whimpered deadly whispers of wrath and as equally

seductive whispers of delight, striving still to be heard, to convey some

cosmic secret, some understanding of infinite import and value. It dwindled to

a ghost of sound that had lost its menace and promise, and became a thing that

pulsed on in the sick man's consciousness for minutes after it had ceased. When

he could hear it no longer, Bassett glanced at his watch. An hour had elapsed

ere that archangel's trump had subsided into tonal nothingness.

Was it months, or years, he asked himself, since

he first heard that mysterious call on the beach at Ringmanu? To save himself,

he could not tell. His long sickness had been most long. In conscious count of

time, he knew of months, many of them; but he had no way of estimating the long

intervals of delirium and stupor. And how fared Captain Bateman of the

blackbirder, Nari, he wondered; and had Captain Bateman's drunken mate died of

delirium tremens yet?

From which vain speculations Bassett turned idly

to review all that had occurred since that day on the beach of Ringmanu when he

first heard the sound and plunged into the jungle after it. Sagawa had

protested. He could see him yet, his queer little monkeyish face eloquent with

fear, his back burdened with specimen-cases, in his hands Bassett's

butterfly-net and naturalist's shotgun, as he quavered in

bêche-de-mer English: "Me fella too much fright along bush.

Bad fella boy too much stop'm along bush."

Bassett smiled sadly at the recollection. The

little New Hanover boy had been frightened, but had proved faithful, following

him without hesitancy into the bush in quest after the source of the wonderful

sound. No fire-hollowed tree-trunk that, throbbing war through the

jungle-depths, had been Bassett's conclusion. Erroneous had been his next

conclusion, namely, that the source or cause could not be more distant than an

hour's walk and that he would easily be back by mid-afternoon, to be picked up

by the Nari's whale-boat.

"That big-fella noise no good, all the same

devil-devil," Sagawa had adjudged. And Sagawa had been right. Had he not

had his head hacked off within the day? Bassett shuddered. Within a minute the

thing had happened. Within a minute, looking back, Bassett had seen him

trudging patiently along under his burdens. Then Bassett's own trouble had come

upon him. He looked at the cruelly healed stumps of the first and second

fingers of his left hand, then rubbed them softly into the indentation in the

back of his skull. Quick as had been the flash of the long-handled tomahawk, he

had been quick enough to duck away his head and partially to deflect the stoke

with his up-flung hand. Two fingers and a nasty scalp-wound had been the price

he paid for his life. With one barrel of his ten-gage shotgun he had blown the

life out of the bushman who had so nearly got him; with the other barrel he had

peppered the bushmen bending over Sagawa, and had the pleasure of knowing that

the major portion of the charge had gone into the one who leaped away with

Sagawa's head.

Everything had occurred in a flash. Only himself,

the slain bushman, and what remained of Sagawa were in the narrow wild-pig-run

of a path. From the dark jungle on either side came no rustle of movement or

sound of life. And he had suffered distinct and dreadful shock. For the first

time in his life, he had killed a human being.

Then had begun the chase. He retreated up the

pig-run before his hunters, who were between him and the beach. How many there

were, he could not guess. There might have been one, or a hundred, for aught he

saw of them. At the most, he never glimpsed more than an occasional flitting of

shadows. No bowstrings twanged that he could hear; but every little while,

whence discharged he knew not, tiny arrows whispered past him or struck

tree-boles and fluttered to the ground beside him.

What a night had followed! Small wonder that he

had accumulated such a virulence and variety of fevers, he thought, as he

recalled that sleepless night of torment, when the throb of his wounds was as

nothing compared with the myriad stings of the mosquitoes. There had been no

escaping them, and he had not dared to light a fire. They had literally pumped

his body full of poison, so that, with the coming of day, eyes swollen almost

shut, he had stumbled blindly on, not caring much when his head should be

hacked off and his carcass started on the way of Sagawa's to the cooking-fire.

Twenty-four hours had made a wreck of him—of mind as well as body. He had

scarcely retained his wits at all, so maddened was he by the tremendous

inoculations of poison. Several times he fired his shotgun with effect into the

shadows that dogged him. Stinging day-insects and gnats added to his torment,

while his bloody wounds attracted hosts of loathsome flies that clung

sluggishly to his flesh and had to be brushed off and crushed off.

Once, in that day, he heard again the wonderful

sound, seemingly more distant, but rising imperiously above the nearer

war-drums in the bush. Right there was where he had made his mistake. Thinking

that he had passed beyond it and that, therefore, it was between him and the

beach of Ringmanu, he had worked back toward it, when, in reality, he was

penetrating deeper and deeper into the mysterious heart of the unexplored

island. That night, crawling in among the twisted roots of a banyan tree, he

had slept from exhaustion, while the mosquitoes had had their will of him.

Followed days and nights that were vague as

nightmares in his memory. One clear vision he remembered was of suddenly

finding himself in the midst of a bush-village and watching the old men and

children fleeing into the jungle. All had fled but one. From close at hand and

above him, a whimpering as of some animal in pain and terror had startled him.

And, looking up, he had seen her—a girl, or young woman, rather,

suspended by one arm in the cooking sun. Perhaps for days she had so hung. Her

swollen, protruding tongue spoke as much. Still alive, she gazed at him with

eyes of terror. Past help, he decided, as he noted the swellings of her legs,

which advertised that the joints had been crushed and the great bones broken.

He resolved to shoot her, and there the vision terminated. He could not

remember whether he had shot her or not, any more than could he remember how he

chanced to be in that village or how he succeeded in getting away from it.

Many pictures, unrelated, came and went in

Bassett's mind as he reviewed that period of his terrible wanderings. But

seared deepest of all in his brain was the dank and noisome jungle. It actually

stank with evil, and it was always twilight. Rarely did a shaft of sunlight

penetrate its matted roof a hundred feet overhead. And beneath that roof was an

aerial ooze of vegetation, a monstrous, parasitic dripping of decadent

life-forms that rooted in death and lived on death. And through all this he

drifted, ever pursued by the flitting shadows of the anthropophagi, themselves

ghosts of evil that dared not face him in battle but that knew, soon or late,

that they would feed on him. Bassett remembered that, at the time, in lucid

moments, he had compared himself to a wounded bull pursued by plains coyotes

too cowardly to battle with him for the meat of him, yet certain of the

inevitable end of him, when they would be gorged. As the bull's horns and

stamping hoofs kept off the coyotes, so his shotgun kept off these Solomon

Islanders, these twilight shades of bushmen of the island of Guadalcanar.

Came the day of the grass-lands. Abruptly, as if

cloven by the sword of God in the hand of God, the jungle terminated. The edge

of it, perpendicular and as black as the infamy of it, was a hundred feet up

and down. And, beginning at the edge of it, grew the grass—sweet, soft,

tender pasture-grass that would have delighted the eyes and beasts of any

husbandman and that extended on and on, for leagues and leagues of velvet

verdure, to the back-bone of the great island, the towering mountain range

flung up by some ancient earth-cataclysm, serrated and gullied by not yet

erased by the erosive tropic rains. But the grass! He had crawled into it a

dozen yards, buried his face in it, smelled it, and broken down in a fit of

involuntary weeping.

And, while he wept, the wonderful sound had

pealed forth—if by "peal," he had often thought since, and

adequate description could be given of the enunciation of so vast a sound so

smelting sweet. Sweet it was as no sound ever heard. Vast it was, of so mighty

a resonance that it might have proceeded from some brazen-throated monster. And

yet it called to him across that leagues'-wide savanna, and was like a

benediction to his long-suffering, pain-racked spirit.

Two days and nights he had spent crawling across

that belt of grass-land. He had suffered much, but pursuit had ceased at the

jungle-edge. And he would have died of thirst had not a heavy thunder-storm

revived him on the second day.

And then had come Balatta. In the first shade,

where the savanna yielded to the dense mountain jungle, he had collapsed to

die. At first she had squealed with delight at sight of his helplessness, and

was for beating his brains out with a stout forest branch. Perhaps it was his

very utter helplessness that had appealed to her, and perhaps it was her human

curiosity that made her refrain. At any rate, she had refrained, for he opened

his eyes again under the impending blow, and saw her studying him intently.

What especially struck her about him were his blue eyes and white skin. Coolly

she had squatted on her hams, spat on his arm, and with her finger-tips

scrubbed away the dirt of days and night of muck and jungle that sullied the

pristine whiteness of his skin.

And everything about her had struck him

especially, although there was nothing conventional about her at all. He

laughed weakly at the recollection, for she had been as innocent of garb as Eve

before the fig-leaf adventure. Squat and lean at the same time, asymmetrically

limbed, string-muscled as if with lengths of cordage, dirt-caked from infancy

save for casual showers, she was as unbeautiful a prototype of woman as he,

with a scientist's eye, had ever gazed upon. Her breasts advertised at the one

time her maturity and youth; and, if by nothing else, her sex was advertised by

the one article of finery with which she was adorned—namely, a pig's tail

thrust through a hole in her left ear-lobe. And her face! A twisted and wizened

complex of apish features, perforated by upturned, sky-open, Mongolian

nostrils, by a mouth that sagged from a huge upper lip and faded precipitately

into a retreating chin, and by peering, querulous eyes that blinked as blink

the eyes of denizens of monkey-cages.

Not even the water she had brought him in a

forest leaf, and the ancient and half-putrid chunk of roast pig could redeem in

the slightest the grotesque hideousness of her. When he had eaten weakly for a

space, he closed his eyes in order not to see her, although again and again she

poked them open to peer at the blue of them. Then had come the sound. Nearer,

much nearer, he knew it to be; and he knew equally well, despite the weary way

he had come, that it was still many hours distant. The effect of it on her had

been startling. She cringed under it, with averted face, moaning and chattering

with fear. But after it had lived its full life of an hour, he closed his eyes

and fell asleep, with Balatta brushing the flies from him.

When he awoke, it was night, and she was gone.

But he was aware of renewed strength, and, by then, too thoroughly inoculated

by the mosquito-poison to suffer further inflammation, he closed his eyes and

slept an unbroken stretch till sunup. A little later, Balatta had returned,

bringing with her half a dozen women, who, unbeautiful as they were, were

patently not so unbeautiful as she. She evidenced by her conduct that she

considered him her find, her property, and the pride she took in showing him

off would have been ludicrous had his situation not been so desperate.

Later, after what had been to him a terrible

journey of miles, when he collapsed in front of the devil-devil house in the

shadow of the breadfruit true, she had shown very lively ideas on the matter of

retaining possession of him. Ngurn, whom Bassett was to know afterward as the

devil-devil doctor, priest, or medicine-man of the village, had wanted his

head. Others of the grinning and chattering monkey-men, all as stark of clothes

and bestial of appearance as Balatta, had wanted his body for the

roasting-oven. At that time, he had not understood their language, if by

"language" might be dignified the uncouth sounds they used to

represent ideas. But Bassett had thoroughly understood the matter of debate,

especially when the men pressed and prodded and felt of the flesh of him.

Balatta had been losing the debate rapidly when

the accident happened. One of the men, curiously examining Bassett's shotgun,

managed to cock and pull a trigger. The recoil of the butt into the pit of the

man's stomach had not been the most sanguinary result, for the charge of shot,

at a distance of a yard, had blown the head of one of the debaters into

nothingness.

Even Balatta joined the others in flight, and, ere they returned, his senses already reeling from the oncoming fever-attack, Bassett had regained possession of the gun. Whereupon, although his teeth chattered with the ague and his swimming eyes could scarcely see, he held onto his fading consciousness until he could intimidate the bushmen with the simple magics of compass, watch, burning-glass, and matches. At the last, with due emphasis of solemnity and awfulness, he had killed a young pig with his shotgun and promptly fainted.

Bassett flexed his arm-muscles in quest of what

possible strength might reside in such weakness, and dragged himself slowly and

totteringly to his feet. He was shockingly emaciated; yet, during the various

convalescences of the many months of his long sickness, he had never regained

quite the same degree of strength as this time. What he feared was another

relapse, such as he had already frequently experienced. Without drugs, without

even quinine, he had managed, so far, to live through a combination of the most

pernicious and most malignant of malarial and black-water fevers. But could he

continue to endure? Such was his everlasting query. For, like the genuine

scientist he was, he would not be content to die until he has solved the secret

of the sound.

Supported by a staff, he staggered the few steps

to the devil-devil house, where death and Ngurn reigned in gloom. Almost as

infamously dark and evil-stinking as the jungle was the devil-devil

house—in Bassett's opinion. Yet therein was usually to be found his

favorite crony and gossip, Ngurn, always willing for a yarn or a discussion,

the while he sat in the ashes of death and, in a slow smoke, shrewdly resolved

curing human heads suspended from the rafters. For, through the months'

intervals of consciousness of his long sickness, Bassett had mastered the

psychological simplicities and lingual difficulties of the language of the

tribe of Ngurn and Balatta and Gngngn—the latter the addle-headed young

chief who was ruled by Ngurn, and who, whispered intrigue had it, was the son

of Ngurn.

"Will the Red One speak to-day?"

Bassett asked, by this time so accustomed to the old man's gruesome occupation

as to take even an interest in the progress of the curing.

"Will the Red One speak to-day?"

Bassett asked, by this time so accustomed to the old man's gruesome occupation

as to take even an interest in the progress of the curing.

With the eye of an expert, Ngurn examined the

particular head he was at work upon.

"It will be ten days before I can say,

'Finish,' " he said. "Never has any man fixed heads like

these."

Bassett smiled inwardly at the old fellow's

reluctance to talk with him of the Red One. It has always been so. Never, by

any chance, had Ngurn or any other member of the weird tribe divulged the

slightest hint of any physical characteristic of the Red One. Physcial the Red

One must be, to emit the wonderful sound, and though it was called the Red One,

Bassett could not be sure that red represented the color of it. Red enough were

the deeds and powers of it, from what abstract clues he had gleaned. Not alone,

had Ngurn informed him, was the Red One more bestial, powerful than the

neighbor tribal gods, ever athirst for the red blood of living human

sacrifices, but the neighbor-gods themselves were sacrificed and tormented

before him. He was the god of a dozen allied villages similar to this one,

which was the central and commanding village of the federation. By virtue of

the Red One, many alien villages had been devastated and even wiped out, the

prisoners sacrificed to the Red One. This was true to-day, and it extended back

into old history, carried down by word of mouth through the generations. When

he, Ngurn, had been a young man, the tribes beyond the grass-lands had made a

war-raid. In the counter-raid, Ngurn and his fighting folk had made many

prisoners. Of children alone, over five score living had been bled white before

the Red One, and many, many more men and women.

The Thunderer, was another of Ngurn's names for

the mysterious deity. Also, at times was he called the Loud Shouter, the

God-voiced, the Bird-throated, the One with the Throat Sweet as the Throat of

the Honey-Bird, the Sun-Singer, and the Star-born.

Why the Star-born? In vain, Bassett interrogated

Ngurn. According to that old devil-devil doctor, the Red One had always been

just where he was at present, forever singing and thundering his will over men.

But Ngurn's father, wrapped in decaying grass-matting and hanging even then

over their heads among the smoky rafters of the devil-devil house, had held

otherwise. That departed wise one had believed that that the Red One came from

out the starry night, else why—so his argument had run—had the old

and forgotten ones passed his name down as the Star-born? Bassett could not but

recognize something cogent in such argument. But Ngurn affirmed the long years

of his long life, wherein he had gazed upon many starry nights, yet never had

he found a star on grass-land or in jungle-depth—and he had looked for

them. True, he had beheld shooting-stars (this in reply to Bassett's

contention); but likewise had he beheld the phosphorescence of fungoid growths

and rotten meat and fireflies on dark nights, and the flames of wood fires and

of blazing candlenuts. Yet what were flame and blaze and glow when they had

flamed and blazed and glowed? Answer: Memories, memories only, of things which

had ceased to be, like memories of matings accomplished, of feasts forgotten,

of desires that were the ghosts of desires, flaring, flaming, burning, yet

unrealized in achievement of easement and satisfaction.

A memory was not a star, was Ngurn's contention.

How could a memory be a star? Further, after all his long life, he still

observed the starry night sky unaltered. Never had he noted the absence of a

single star from its accustomed place. Besides, stars were fire, and the Red

One was not fire—which last involuntary betrayal told Bassett

nothing.

"Will the Red One speak to-morrow?" he

queried. Ngurn shrugged hius shoulders as who would say. "And the day

after—and the day after that?" Bassett persisted.

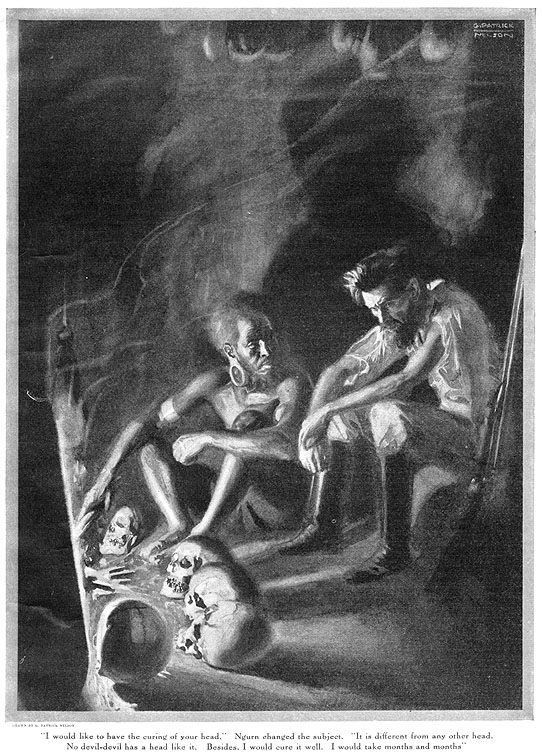

"I would like to have the curing of your

head," Ngurn changed the subject. "It is different from the other

head. No devil-devil has a head like it. Besides, I would cure it well. I would

take months and months. The skin would not wrinkle. It would be as smooth as

your skin now."

He stood up, and from the dim rafters, grimed

with the smoking of countless heads, where day was no more than a gloom, took

down a matting-wrapped parcel and began to open it.

"It is a head like yours," he said,

"but it is poorly cured."

Bassett had pricked up his ears at the suggestion

that it was a white man's head; for he had long since come to accept that these

jungle-dwellers, in the midmost center of the great island, had never had

intercourse with white men. Certainly he had found them without the almost

unversal bêche-de-mer English of the west South Pacific. Nor had

they knowledge of tobacco or of gunpowder.

"The folk in the out-beyond do not know how

to cure heads," old Ngurn explained, as he drew forth from the filthy

matting and placed in Bassett's hands an indubitable white man's head.

Ancient it was beyond question; white it was, as

the blond hair attested. He could have sworn it once belonged to an Englishman

and to an Englishman of long before, by token of the heavy gold circlets still

threaded in the withered ear-lobes.

"Now, your head—" The devil-devil

doctor began on his favorite topic.

"I'll tell you what," Bassett

interrupted, struck by a new idea: "When I die, I'll let you have my head

to cure, if, first, you take me to look upon the Red One."

"I will have your head, anyway, when you are

dead," Ngurn rejected the proposition. He added, with the brutal frankness

of the savage: "Besides, you have not long to live. You are almost a dead

man now. You will grow less strong. In not many months I shall have you here

turning and turning in the smoke. It is pleasant, through the long afternoons,

to turn the head of one you have known as well as I know you. And I shall talk

to you and tell you the many secrets you want to know. Which will not matter,

for you will be dead."

"Ngurn," Bassett threatened in sudden

anger, "you know the Baby-Thunder-in-the-Iron that is mine." (This

was in reference to his all-potent and all-awful shotgun.) "I can kill you

any time, and then you will not get my head."

"Just the same will Gngngn or some one else

of my folk get it," Ngurn complacently assured him.

And Bassett knew he was beaten in the discussion.

What was the Red One?—Bassett asked himself

a thousand times in the succeeding week, while he seemed to grow stronger. What

was the source of the wonderful sound? What was this Sun-Singer, this Star-born

One, this mysterious deity, as bestial-conducted as the black and kinky-headed

and monkeylike human beasts who worshiped it, and whose silver-sweet,

bull-mouthed singing and commanding he had heard at the tabu-distance for so

long?

Ngurn had he failed to bribe with the inevitable

curing of his head when he was dead. Gngngn, imbecile and chief that he was,

was too imbecilic, too much under the sway of Ngurn to be considered. Remained

Balatta, who, from the time she found him and poked his blue eyes open to

recrudescence of her grotesque female hideousness, had continued his adorer.

Woman she was, and he had long known that the only way to win from her treason

to her tribe was through the woman's heart of her.

Bassett was a fastidious man. He had never

recovered from the initial horror caused by Balatta's female awfulness. Back in

England, even at best, the charm of woman to him had never been robust. Yet

now, resolutely, as only a man can do who is capable of martyring himself for

the cause of science, he proceeded to violate all the fineness and delicacy of

his nature by making love to the unthinkably disgusting bushwoman.

He shuddered, but with averted face hid his

grimaces and swallowed his gorge as he put his arm round her dirt-crusted

shoulders and felt the contact of her rancid-oily and kinky hair with his neck

and chin. But he nearly screamed when she succumbed to that caress at the very

first of the courtship, and mowed and gibbered and squealed little, queer,

piglike gurgly noises of delight. It was too much. And the next he did in the

singular courtship was to take her down to the stream for a vigorous

scrubbing.

From then on, he devoted himself to her like a

true swain as frequently and for as long at a time as his will could override

his repugnance. But marriage, which she ardently suggested, with due observance

of tribal custom, he balked at. Fortunately, tabu rule was strong in the tribe.

Thus, Ngurn could never touch bone or flesh or hide of crocodile. This had been

ordained at his birth. Gngngn was denied ever the touch of woman. As for

Balatta, the breadfruit was tabu to her. For which Bassett was thankful. The

tabu might have been water.

For himself, he fabricated a special tabu. Only

could he marry, he explained, when the Southern Cross rode highest in the sky.

Knowing his astronomy, he thus gained a reprieve of nearly nine months; and he

was confident that within that time he would either be dead or escaped to the

coast with the full knowledge of the Red One and of the source of the Red One's

wonderful voice. At first, he had fancied the Red One to be some colossal

statue, like Memnon, rendered vocal under certain temperature-conditions of

sunlight. But when, after a war-raid, a batch of prisoners was brought in and

the sacrifice was made at night, in the midst of rain, when the sun could play

no part, and the Red One had been more vocal than usual, Bassett discarded that

hypothesis.

In company with Balatta, sometimes with men and

parties of women, the freedom of the jungle was his for three quadrants of the

compass. But the fourth quadrant, which contained the Red One's abiding-place,

was tabu. He made more thorough love to Balatta—also saw to it that she

scrubbed herself more frequently. Eternal female she was, capable of any

treason for the sake of love. And, though the sight of her was provocative of

nausea and the contact of her provocative of despair, although he could not

escape her awfulness in his dream-haunted nightmares of her, he nevertheless

was aware of the cosmic verity of sex that animated her and that made her own

life of less value than the happiness of her lover with whom she hoped to mate.

Juliet or Balatta? Where was the intrincic difference?

Bassett was a scientist first, a humanist

afterward. In the jungle-heart of Guadalcanar, he put the affair to the test,

as in the laboratory he would have put to the test any chemical reaction. He

increased his feigned ardor for the bushwoman, at the same time increasing the

imperiousness of his will of desire over her to be led to look upon the Red One

face to face. It was the old story, he recognized, that the woman must pay, and

it occurred when the two of them, one day, were catching the unclassified and

unnamed little black fish, an inch long, half eel and half scaled, rotund with

salmon-golden roe, that frequented the fresh water and that were esteemed, raw

and whole, fresh or putrid, a perfect delicacy. Prone in the muck of the

decaying jungle-floor, Balatta threw herself, clutching his ankles with her

hands, kissing his feet and making slubbery noises that chilled his back-bone

up and down again. She begged him to kill her rather than exact this ultimate

love-payment. She told him the penalty of breaking the tabu of the Red

One—a week of torture, living, the details of which she yammered out from

her face in the mire until he realized that he was yet a tyro in knowledge of

the frightfulness the human was capable of wreaking on the human.

Yet did Bassett insist on having his man's will

satisfied at the woman's risk, that he might solve the mystery of the Red One's

singing, though she should die long and horribly and screaming. And Balatta,

being mere woman, yielded. She led him into the forbidden quadrant. An abrupt

mountain, shouldering in from the north to meet a similar intrusion from the

south, tormented the stream in which they had fished into a deep and gloomy

gorge. After a mile along the gorge, the way plunged sharply upward until they

crossed a saddle of raw limestone which attracted his geologist's eye. Still

climbing, although he paused often from sheer physical weakness, they scaled

forest-clad heights until they emerged on a naked mesa or table-land. Bassett

recognized the stuff of its composition as black volcanic sand, and knew that a

pocket-magnet could have captured a full load of the sharply angular grains he

trod upon.

And then, holding Balatta by the hand and leading

her onward, he came to it—a tremendous pit, obviously artificial, in the

heart of the plateau. Old history, the South Seas "Sailing

Directions," scores of remembered data and connotations swift and furious

surged through his brain. It was old Mendaña who had discovered the

islands and named them Solomon's, believing that he had found that monarch's

fabled mines. They had laughed at the old navigator's childlike credulity; and

yet here stood himself, Bassett, on the rim of an excavation for all the world

like the diamond-pits of South Africa.

But no diamond this that he gazed down upon.

Rather was it a pearl, with the depth of iridescence of a pearl, but of a size

all pearls of earth and time, welded into one, could not have totaled, and of a

color undreamed of any pearl, or of anything else, for that matter, for it was

the color of the Red One. And the Red One himself, Bassett knew it to be on the

instant—a perfect sphere, fully two hundred feet in diameter. He likened

the color-quality of it to lacquer. Indeed, he took it to be some sort of

lacquer applied by man, but a lacquer too marvelously clever to have been

manufactured by the bush-folk. Brighter than bright cherry-red, its richness of

color was as if it were red builded upon red. It glowed and iridesced in the

sunlight, as if gleaming up from underlay under underlay of red.

In vain, Balatta strove to dissuade him from

descending. She threw herself in the dirt; but, when he continued down the

trail that spiraled the pit wall, she followed, cringing and whimpering her

terror. That the red sphere had been dug out as a precious thing was patent.

Considering the paucity of members of the federated twelve villages and their

primitive tools and methods, Bassett knew that the toil of a myriad generations

could hardly have made that enormous excavation.

He found the pit bottom carpeted with human

bones, among which, battered and defaced, lay village-gods of wood and stone.

Some, covered with obscene totemic figures and designs, were carved from solid

tree-trunks forty or fifty feet in length. He noted the absence of the shark

and turtle gods, so common among the shore villages, and was amazed at the

constant recurrence of the helmet motive. What did these jungle savages of the

dark heart of Guadalcanar know of helmets? Had Mendaña's men-at-arms

worn helmets and penetrated here centuries before? And if not, then whence had

the bush-folk caught the motive.

Advancing over the litter of gods and bones,

Balatta whimpering at his heels, Bassett entered the shadow of the Red One and

passed on under its gigantic overhang until he touched it with his finger-tips.

No lacquer that. Nor was the surface smooth as it should have been in the case

of lacquer. On the contrary, it was corrugated and pitted, with here and there

patches that showed signs of heat and fusing. Also, the substance of it was

metal, though unlike any metal or combination of metals he had ever known. As

for the color itself, he decided it to be no application. It was the intrinsic

color of the metal itself.

He moved his finger-tips, which, up to that, had

merely rested, along the surface, and felt the whole gigantic sphere quicken

and live and respond. It was incredible! So light a touch on so vast a mass!

Yet did it quiver under the finger-tip caress in rhythmic vibrations that

became whisperings and rustlings and mutterings of sound—but of sound so

different, so elusive thin that it was shimmeringly sibilant, so mellow that it

was maddening sweet, piping like an elfin horn, which last was just what

Bassett decided would be like a peal from some bell of the gods reaching

earthward from across space.

He looked to Balatta with swift questioning; but

the voice of the Red One had had evoked had flung her face downward and moaning

among the bones. He returned to contemplation of the prodigy. Hollow it was,

and of no metal known on earth, was his conclusion. It was right-named by the

ones of old times as the Star-born. Only from the stars could it have come, and

no thing of chance was it. It was a creation of artifice and mind. Such

perfection of form, such hollowness that it certainly possessed could not be

the result of mere fortuitousness. A child of intelligence, remote and

unguessable, working corporeally in metals, it indubitally was. He stared at it

in amaze, his brain a racing wild-fire of hypotheses to account for this

far-journeyer who had adventured the night of space, threaded the stars, and

now rose before him and above him, exhumed by patient anthropophagi, pitted and

lacquered by its fiery bath in two atmospheres.

But was the color a lacquer of heat upon some

familiar metal? Or was it an intrinsic quality of the metal itself? He thrust

in the blade-point of his pocket-knife to test the constitution of the stuff.

Instantly the entire sphere burst into a mighty whispering, sharp with protest,

almost twanging goldenly, if a whisper could possibly be considered to twang,

rising higher, sinking deeper, the two extremes of the registry of sound

threatening to complete the circle and coalesce into the bull-mouthed

thundering he had so often heard beyond the tabu-distance.

Forgetful of safety, of his own life itself,

entranced by the wonder of the unthinkable and unguessable thing, he raised his

knife to strike heavily from a long stroke, but was prevented by Balatta. She

upreared on her own knees in agony of terror, clasping his knees and

supplicating him to desist. In the intensity of her desire to impress him, she

put her forearm between her teeth and sank them to the bone.

He scarcely observed her act, although he yielded

automatically to his gentler instincts and withheld the knife-hack. To him,

human life had dwarfed to microscopic proportions before this colossal portent

of higher life from within the distances of the sidereal universe. As had she

been a dog, he kicked the ugly little bushwoman to her feet, and compelled her

to start with him on an encirclement of the base. Part-way round, he

encountered horrors. Truly had the bush-folk named themselves into the name of

the Red One, seeing in him their own image, which they strove to placate and

please with red offerings.

Farther round, always treading the bones and

images of humans and gods that constituted the floor of this ancient

charnel-house of sacrifice, he came upon the device by which the Red One was

made to send his call singing thunderingly across the jungle-belts and

grass-lands to the far beach of Ringmanu. Simple and primitive it was as was

the Red One consummate artifice. A great king-post, half a hundred feet in

length, seasoned by centuries of superstitious care, carven into dynasties of

gods, each superimposed, each helmeted, each seated in the open mouth of a

crocodile, was slung by ropes, twisted of climbing vegetable parasites, from

the apex of a tripod of three great forest trunks, themselves carved into

grinning and grotesque adumbrations of man's modern concepts of art and god.

From the striker king-post were suspended ropes of climbers, to which men could

apply their strength and direction. Like a battering-ram, this king-post could

be driven end-onward against the mighty red-iridescent sphere.

Here was where Ngurn officiated and functioned

religiously for himself and the twelve tribes under him. Bassett laughed aloud,

almost with madness, at the thought of this wonderful messenger winged with

intelligence across space to fall into a bushman stronghold and be worshiped by

apelike, man-eating, and head-hunting savages. It was as if God's word had

fallen into the muck-mire of the abyss underlying the bottom of hell, as if

Jehovah's commandments had been presented on carved stone to the monkeys of the

monkey-cage at the zoo, as if the Sermon on the Mount had been preached in a

roaring bedlam of lunatics.

The slow weeks passed. The nights, by election,

Bassett spent on the ashen floor of the devil-devil house beneath the

ever-swinging, slow-curing heads. His reason for this was that it was tabu to

the lesser sex of woman, and, therefore, a refuge from him from Balatta, who

grew more persecutingly and perilously loverly as the Southern Cross rode

higher in the sky and marked the imminence of her coming nuptials. His days,

Bassett spent in a hammock swung under the shade of the great breadfruit tree

before the devil-devil house. There were breaks in the program, when, in the

comas of his devastating fever-attacks, he lay for days and nights in the house

of heads. Ever he struggled to combat the fever, to live, to continue to live,

to grew strong and stronger against the day when he would be strong enough to

dare the grass-lands and the belted jungle beyond, and win to the beach and to

some labor-recruiting, blackbirding ketch or schooner, and on to civilization

and the men of civilization, to whom he could give news of the message from

other worlds that lay, darkly worshiped by beast-men, in the black heart of

Guadalcanar's midmost center.

On other nights, lying late under the breadfruit

tree, Bassett spent long hours watching the slow setting of the western starts

beyond the black wall of jungle where it had been thrust back by the clearing

for the village. Possessed of more than a cursory knowledge of astronomy, he

took a sick man's pleasure in speculating as to the dwellers on the unseen

worlds of those incredibly remote suns, to haunt whose houses of light life

came forth, a shy visitant from the rayless crypts of matter. He could no more

apprehend limits to time than bounds to space. No subversive

radium-speculations had shaken his steady scientific faith in the conservation

of energy and the indestructibility of matter. Always and forever must there

have been stars. And surely, in that cosmic ferment, all must be comparatively

alike, comparatively of the same substance, or substances, save for the freaks

of the ferment. All must obey or compose the same laws that ran without

infraction through the entire experience of man. Therefore, he argued and

agreed, must worlds and life be appanages to all the suns as they were

appanages to the particular sun of his own solar system.

Even as he lay here, under the breadfruit tree,

an intelligence that stared across the starry gulfs, so must all the universe

be exposed to the ceaseless scrutiny of innumerable eyes like his, though

grantedly different, with behind them, by the same token, intelligences that

questioned and sought the meaning and the construction of the whole. So

reasoning, he felt his soul go forth in kinship with that august company, that

multitude whose gaze was forever upon the arras of infinity.

Who were they, what were they, those far-distant

and superior ones who had bridged the sky with their gigantic, red-iridescent,

heaven-singing message? Surely, and long since, had they, too, trod the path on

which man had so recently, by the calendar of the cosmos, set his feet. And to

be able to send such a message across the pit of space, surely they had reached

those heights to which man, in tears and travail and bloody sweat, in darkness

and confusion of many counsels, was so slowly struggling. And what were they on

their heights? Had they won Brotherhood? Or had they learned that the law of

Love imposed the penalty of weakness and decay? Was strife life? Was the rule

of all the universe the pitiless rule of natural selection? And, most

immediately and poignantly, was their far conclusions, their long-won wisdoms

shut, even then, in the huge, metallic heart of the Red One, waiting for the

first earth-man to read? Of one thing he was certain: No drop of red dew shaken

from the lion-mane of some sun in torment was the sounding sphere. It was of

design, not chance, and it contained the speech and wisdom of the stars.

What engines and elements and mastered forces,

what lore and mysteries and destiny-control might be there! Undoubtedly, since

so much could be inclosed in so little a thing as the foundation-stone of a

public building, this tremendous sphere should contain vast histories,

profounds of research beyond man's wildest guesses, laws and formulas that,

easily mastered, would make man's life on earth, individual and collective,

spring up from its present mire to inconceivable heights of purity and power.

It was Time's greatest gift to blindfold, insatiable, and sky-aspiring man. And

to him, Bassett, had been vouchsafed the lordly fortune to be the first to

receive this message from man's interstellar kin.

No white man, much less no outland man of the

other bus-tribes, had gazed upon the Red One and lived. Such the law expounded

by Ngurn to Bassett. There was such a thing as blood-brotherhood, Bassett, in

return, had often argued in the past. But Ngurn had stated solemnly,

"No." Even the blood-brotherhood was outside the favor of the Red

One. Only a man born within the tribe could look upon the Red One and live. But

now, his guilty secret known only to Balatta, whose fear of immolation before

the Red One fast-sealed her lips, the situation was different. What he had to

do was to recover from the abominable fevers that weakened him and gain to

civilization. Then would he lead an expedition back, and, although the entire

population of Guadalcanar be destroyed, extract from the heart of the Red One

the message to the world from other worlds.

But Bassett's relapses grew more frequent, his

brief convalescences less and less vigorous, his periods of coma longer, until

he came to know, beyond the last promptings of the optimism inherent in so

tremendous constitution as his own, that he would never live to cross the

grass-lands, perforate the perilous coast-jungle, and reach the sea. He faded

as the Southern Cross rose higher in the sky, till even Balatta knew that he

would be dead ere the nuptial date determined by his tabu. Ngurn made

pilgrimage personally and gathered the smoke-materials for the curing of

Bassett's head, and to him made proud announcement and exhibition of the

artistic perfectness of his intention when Bassett should be dead. As for

himself, Bassett was not shocked. Too long and too deeply had life ebbed down

in him to bite him with fear of its impending extinction.

Came the day when all mists and cobwebs

dissolved, when he found his brain clear as a bell, and took just appraisement

of his body's weakness. Neither hand nor foot could lift. So little control of

his body did he have that he was hardly aware of possessing one. Lightly indeed

his flesh sat upon his soul, and his soul, in its briefness of clarity, knew,

by its very clarity, that the black cessation was near. He knew the end was

close, knew that in all truth he had with his eyes beheld the Red One, the

messenger between the worlds, knew that he would never live to carry that

message to the world—that message, for aught to the contrary, which might

already have waited man's hearing in the heart of Guadalcanar for ten thousand

years. And Bassett stirred with resolve, calling Ngurn to him out under the

shade of the breadfruit tree, and with the old devil-devil doctor discussed the

terms and arrangements of his last life-effort, his final adventure in the

quick of the flesh.

"I know the law, O Ngurn!" he concluded

the matter. "Whoso is not of the folk may not look upon the Red One and

live. I shall not live, anyway. Your young men shall carry me before the face

of the Red One, and I shall look upon him and hear his voice, and thereupon die

under your hand, O Ngurn! Thus will three things be satisfied—the law, my

desire, and your quicker possession of my head, for which all your preparations

wait."

To which Ngurn consented, adding:

"It is better so. A sick man who cannot get

well is foolish to live on for so little a while. Also, is it better for the

living that he should go. You have been much in the way of late. Not but what

it was good for me to talk to such a wise one. But for moons of days we have

held little talk. Instead, you have taken up room in the house of heads, making

noises like a dying pig, or talking much and loudly in your own language, which

I do not understand. This has been a confusion to me, for I like to think on

the great things of the light and dark as I turn the heads in the smoke. Your

much noise has thus been a disturbance to the long-learning and hatching of the

final wisdoms that will be mine before I die. As for you, upon whom the Dark

has already brooded, it is well that you die now. And I promise you, in the

long days to come when I turn your head in the smoke, no man of the tribe shall

come in to disturb us. And I will tell you many secrets, for I am an old man

and very wise, and I shall be adding wisdom to wisdom as I turn your head in

the smoke."

So a litter was made, and, borne on the shoulders

of half a dozen of the men, Bassett departed on the last little adventure that

was to cap the total adventure, for him, of living. With a body of which he was

scarcely aware, for even the pain had been exhausted out of it, and with a

bright, clear brain that accommodated him to a quiet ecstasy of sheer lucidness

of thought, he lay back on the lurching litter and watched the fading of the

passing world, beholding for the last time the breadfruit tree before the

devil-devil house, the dim day beneath the matted jungle roof, the gloomy gorge

between the shouldering mountains, the saddle of raw limestone, and the mesa of

black volcanic sand.

Down the spiral path of the pit they bore him,

encircling the sheening, glowing Red One that seemed ever imminent to iridesce

from color and light into sweet thunder. And over bones and logs of immolated

men and gods they bore him, past the horrors of other immolated ones that yet

lived, to the three-king-post tripod and the huge king-post striker.

Here Bassett, helped by Ngurn and Balatta, weakly

sat up, swaying weakly from the hips, and, with clear, unfaltering, all-seeing

eyes, gazed upon the Red One.

"Once, O Ngurn—" he said, not

taking his eyes from the sheening, vibrating surface whereon and wherein all

the shades of cherry-red played unceasingly, ever aquiver to change into sound,

to become silken rustlings, silvery whisperings, golden thrummings of cords,

velvet pipings of elf-land, mellow distances of thunderings.

"I wait," Ngurn prompted, after a long

pause, the tomahawk unassumingly ready in his hand.

"Once, O Ngurn," Bassett repeated,

"let the Red One speak, so that I may see it speak as well as hear it.

Then strike, thus, when I raise my hand; for, when I raise my hand, I shall

drop my head forward and made place for the stroke at the base of my neck. But,

O Ngurn, I, who am about to pass out of the light of day forever, would like to

pass with the wonder-voice of the Red One singing greatly in my ears."

"And I promise you that never will a head be

so well cured as yours," Ngurn assured him, at the same time signaling the

tribesmen to man the propelling ropes suspended from the king-post striker.

"Your head shall be my greatest piece of work in the curing of

heads."

Bassett smiled quietly to the old one's conceit

as the great carved log, drawn back through two-score feet of space, was

released. The next moment, he was lost in ecstasy at the abrupt and thunderous

liberation of sound. But such thunder! Mellow it was with preciousness of all

sounding metals. Archangels spoke in it; it was magnificently beautiful before

all other sounds; it was invested with the intelligence of supermen of planets

of other suns; it was the voice of God, seducing and commanding to be heard.

And—the everlasting miracle of that interstellar metal! Bassett, with his

own eyes, saw color and colors transform into sound till the whole visible

surface of the vast sphere was acrawl and titillant and vaporous with what he

could not tell was color or was sound. In that moment, the interstices of

matter were his, and the interfusings and intermating transfusions of matter

and force.

Time passed. At the last, Bassett was brought

back from his ecstasy by an impatient movement of Ngurn. He had quite forgotten

the old devil-devil one. A quick flash of fancy brought a husky chuckle into

Bassett's throat. His shotgun lay beside him in the litter. All he had to do,

muzzle to head, was press the trigger and blow his own head into

nothingness.

But why cheat him, was Bassett's next thought.

Head-hunting, cannibal beast of a human that was as much ape as human,

nevertheless old Ngurn had, according to his lights, played squarer than

square. He was in himself a forerunner of ethics and contract, of consideration

and gentleness in man. No, Bassett decided; it would be a ghastly pity and an

act of dishonor to cheat the old fellow at the last. His head was Ngurn's, and

Ngurn's head to cure it would be.

And Bassett, raising his hand in signal, bending

forward his head as agreed, so as to expose cleanly the articulation to his

taut spinal cord, forgot Balatta, who was merely a woman, a woman merely and

only and undesired. He knew, without seeing, when the razor-edged hatchet rose

in the air behind him. And for that instant, ere the end, there fell upon

Bassett the shadow of the Unknown, a sense of impending marvel of the rendering

of walls before the Imaginable. Almost, when he knew the blow had started and

just ere the edge of steel bit the flesh and nerves, it seemed that he gazed

upon the serene face of the Medusas, Truth. And, simultaneous with the bite of

steel on the onrush of the Dark, in a flashing instant of fancy, he saw the

vision of his head turning slowly, always turning in the devil-devil house

beside the breadfruit tree.

Back to the Jack London First Editions.