Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

|

"Now I wake me up to work; I pray the Lord I may not shirk. If I should die before the night, I pray the Lord my work's all right. Amen." |

![]() F YOU don't

git up, Johnny, I won't give you a bite to eat."

F YOU don't

git up, Johnny, I won't give you a bite to eat."

The threat had no effect on the boy. He clung

stubbornly to sleep, fighting for its oblivion as the dreamer fights for his

dream. The boy's hands loosely clenched themselves, and he made feeble,

spasmodic blows at the air. These blows were intended for his mother, but she

betrayed practiced familiarity in avoiding them as she shook him roughly by the

shoulder.

"Lemme 'lone!"

It was a cry that began, muffled, in the deeps of

sleep; that swiftly rushed upward, like a wail, into passionate belligerence,

and that died away and sank down into an inarticulate whine. It was a bestial

cry, as of a soul in torment, filled with infinite protest and pain.

But she did not mind. She was a sad-eyed,

tired-faced woman, and she had grown used to this task, which she repeated

every day of her life. She got a grip on the bedclothes and tried to strip them

down; but the boy, ceasing his punching, clung to them desperately. In a huddle

at the foot of the bed, he still remained covered. Then she tried dragging the

bedding to the floor. The boy opposed her. She braced herself. Hers was the

superior weight, and the boy and bedding, the former instinctively following

the latter in order to shelter against the chill of the room that bit into his

body.

As he toppled on the edge of the bed it seemed

that he must fall head-first to the floor. But consciousness fluttered up in

him. He righted himself and for a moment perilously balanced. Then he struck

the floor on his feet. On the instant his mother seized him by the shoulders

and shook him. Again his fists struck out, this time with more force and

directness. At the same time his eyes opened. She released him. He was

awake.

"All right," he mumbled.

She caught up the lamp and hurried out, leaving

him in darkness.

"You'll be docked," she warned back to

him.

He did not mind the darkness. When he had got

into his clothes he went out into the kitchen. His tread was very heavy for so

thin and light a boy. His legs dragged with their own weight, which seemed

unreasonable because they were such skinny legs. He drew a broken-bottomed

chair to the table.

"Johnny!" his mother called

sharply.

He arose as sharply from the chair, and without a

word went to the sink. It was a greasy, filthy sink. A smell came up from the

outlet. He took no notice of it. That a sink should smell was to him part of

the natural order, just as it was part of the natural order that soap should be

grimy with dish-water and hard to lather. Nor did he try very hard to make it

lather. Several splashes of cold water from the running faucet completed the

function. He did not wash his teeth. For that matter he had never seen a

tooth-brush, nor did he know that there existed beings in the world who were

guilty of so great a foolishness as tooth-washing.

"You might wash yourself wunst a day without

bein' told," his mother complained.

She was holding a broken lid on the pot as she

poured two cups of coffee. He made no remark, for this was a standing quarrel

between them, and the one thing upon which his mother was hard as adamant.

"Wunst" a day it was compulsory that he should wash his face. He

dried himself on a greasy towel, damp and dirty and ragged, that left his face

covered with shreds of lint.

"I wish we didn't live so far away,"

she said, as he sat down. "I try to do the best I can. You know that. But

a dollar on the rent is such a savin', an' we've more room here. You know

that."

He scarcely followed her. He had heard it all

before, many times. The range of her thought was limited, and she was ever

harking back to the hardship worked upon them by living so far from the

mills.

"A dollar means more grub," he remarked

sententiously. "I'd sooner do the walkin' an' git the grub."

He ate hurriedly, half-chewing the bread and

washing the unmasticated chunks down with coffee. The hot and muddy liquid went

by the name of coffee. Johnny thought it was coffee—and excellent coffee. That

was one of the few of life's illusions that remained to him. He had never drunk

real coffee in his life.

In addition to the bread there was a small piece

of cold pork. His mother refilled his cup with coffee. As he was finishing the

bread, he began to watch if more was forthcoming. She intercepted his questing

glance.

"Now don't be hoggish, Johnny," was her

comment. "You've had your share. Your brothers an' sisters are smaller'n

you."

He did not answer the rebuke. He was not much of

a talker. Also, he ceased his hungry glancing for more. He was uncomplaining,

with a patience that was as terrible as the school in which it had been

learned. He finished his coffee, wiped his mouth on the back of his hand, and

started to rise.

"Wait a second," she said hastily.

"I guess the loaf kin stand you another slice—a thin un."

There was legerdemain in her actions. With all

the seeming of cutting a slice from the loaf for him, she put the loaf and

slice back in the bread-box and conveyed to him one of her own two slices. She

believed she had deceived him, but he had noted her sleight-of-hand.

Nevertheless he took the bread shamelessly. He had a philosophy that his

mother, what of her chronic sickliness, was not much of an eater anyway.

She saw that he was chewing the bread dry, and

reached over and emptied her coffee cup into his.

"Don't set good somehow on my stomach this

mornin'," she explained.

A distant whistle, prolonged and shrieking,

brought both of them to their feet. She glanced at the tin alarm-clock on the

shelf. The hands stood at half-past five. The rest of the factory world was

just arousing from sleep. She drew a shawl about her shoulders, and on her head

but a dingy hat, shapeless and ancient.

"We've got to run," she said, turning

the wick of the lamp and blowing down the chimney.

They groped their way out and down the stairs. It

was clear and cold, and Johnny shivered at the first contact with the outside

air. The stars had not yet begun to pale in the sky, and the city lay in

blackness. Both Johnny and his mother shuffled their feet as they walked. There

was no ambition in the leg muscles to swing the feet clear of the ground.

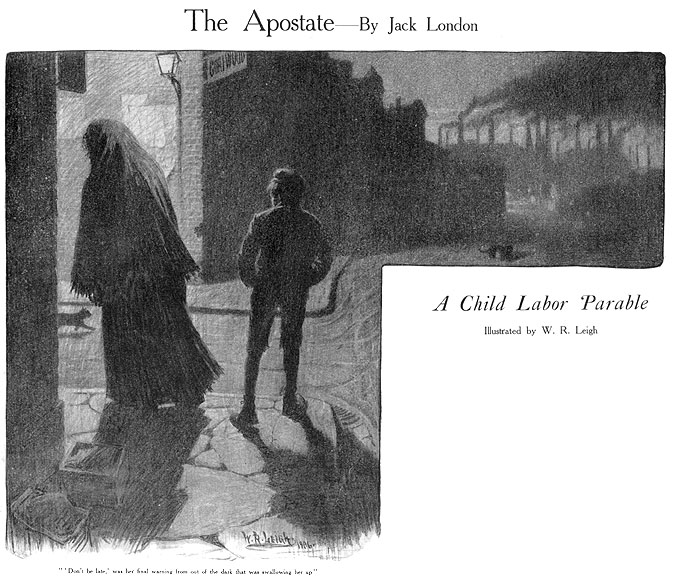

After fifteen silent minutes, his mother turned

off to the right.

"Don't be late," was her final warning

from out of the dark that was swallowing her up.

He made no response, steadily keeping on his way.

In the factory quarter, doors were opening everywhere, and he was soon one of a

multitude that pressed onward through the dark. As he entered the factory gate

the whistle blew again. He glanced at the east. Across a ragged sky-line of

housetops a pale light was beginning to creep. This much he saw of the day as

he turned his back upon it and joined his work-gang.

He took his place in one of many long rows of

machines. Before him, above a bin filled with small bobbins, were large bobbins

revolving rapidly. Upon these he wound the jute-twine of the small bobbins. The

work was simple. All that was required was celerity. The small bobbins were

emptied so rapidly, and there were so many large bobbins that did the emptying,

that there were not idle moments.

He worked mechanically. When a small bobbin ran

out, he used his left hand for a brake, stopping the large bobbin and at the

same time, with thumb and forefinger, catching the flying end of twine. Also,

at the same time, with his right hand, he caught up the loose twine-end of a

small bobbin. These various acts with both hands were performed simultaneously

and swiftly. Then there would come a flash of his hands as he looped the

weaver's knot and released the bobbin. There was nothing difficult about

weaver's knots. He once boasted he could tie them in his sleep. And for that

matter, he sometimes did, toiling centuries long in a single night at tying an

endless succession of weaver's knots.

Some of the boys shirked, wasting time and

machinery by not replacing the small bobbins when they ran out. And there was

an overseer to prevent this. He caught Johnny's neighbor at the trick and

boxed his ears.

"Look at Johnny there—why ain't you like

him?" the overseer wrathfully demanded.

Johnny's bobbins were running full blast, but he

did not thrill at the indirect praise. There had be a time . . . but that was

long ago, very long ago. His apathetic face was expressionless as he listened

to himself being held up as a shining example. He was the perfect worker. He

knew that. He had been told so, often. It was a commonplace, and besides it

didn't seem to mean anything to him any more. From the perfect worker he had

evolved into the perfect machine. When his work went wrong, it was with him as

with the machine, due to faulty material. It would have been as possible for a

perfect nail-die to cut imperfect nails as for him to make a mistake.

And small wonder. There had never been a time when

he had not been in intimate relationship with machines. Machinery had almost

been bred into him, and at any rate he had been brought up on it. Twelve years

before, there had been a small flutter of excitement in the loom-room of this

very mill. Johnny's mother had fainted. They stretched her out on the floor in

the midst of the shrieking machines. A couple of elderly women were called from

their looms. The foreman assisted. And in a few minutes there was one more soul

in the loom-room than had entered by the doors. It was Johnny, born with the

pounding, crashing roar of the looms in his ears, drawing with his first breath

the warm moist air that was thick with flying lint. He had coughed that first

day in order to rid is lungs of the lint; and for the same reason he had

coughed ever since.

The boy alongside of Johnny whimpered and

sniffed. The boy's face was convulsed with hatred for the overseer who kept a

threatening eye on him from a distance; but every bobbin was running full. The

boy yelled terrible oaths into the whirling bobbins before him; but the sound

did not carry half a dozen feet, the roaring of the room holding it in and

containing it like a wall.

Of all this Johnny took no notice. He had a way

of accepting things. Besides, things grow monotonous by repetition, and this

particular happening he had witnessed many times. It seemed to him as useless

to oppose the overseer as to defy the will of a machine. Machines were made to

go in certain ways and to perform certain tasks. It was the same with the

overseer.

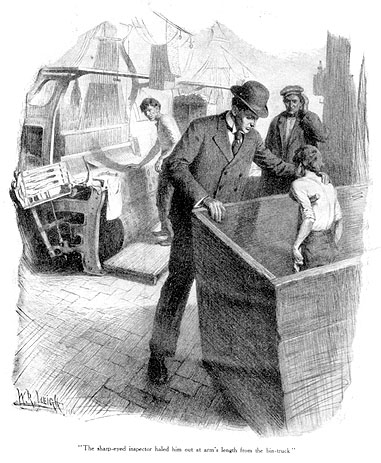

But at eleven o'clock there was excitement in the

room. In an apparently occult way the excitement instantly permeated

everywhere. The one-legged boy who worked on the other side of Johnny bobbed

swiftly across the floor to a bin-truck that stood empty. Into this he dived

out of sight, crutch and all. The superintendent of the mill was coming along,

accompanied by a young man. He was well-dressed and wore a starched shirt—a

gentleman, in Johnny's classification of men, and also, "the

Inspector."

He looked sharply at the boys as he passed along.

Sometimes he stopped and asked questions. When he did so he was compelled to

shout at the top of his lungs, at which moments his face was ludicrously

contorted with the strain of making himself heard. His quick eye noted the

empty machine alongside of Johnny's, but he said nothing. Johnny also caught

his eye, and he stopped abruptly. He caught Johnny by the arm to draw him back

a step from the machine; but with an exclamation of surprise he released the

arm.

"Pretty skinny," the superintendent

laughed anxiously.

"Pipe-stems," was the answer.

"Look at those legs. The boy's got the rickets—incipient, but he's got

them. If epilepsy doesn't get him in the end, it will be because tuberculosis

gets him first."

Johnny listened, but did not understand.

Furthermore he was not interested in future ills. There was an immediate and

more serious ill that threatened him in the form of the inspector.

"Now, my boy, I want you to tell me the

truth," the inspector said, or shouted, bending close to the boy's ear to

make him hear. "How old are you?"

"Fourteen," Johnny lied, and he lied

with the full force of his lungs. So loudly did he lie that it started him off

in a dry, hacking cough that lifted the lint which had been settling in his

lungs all morning.

"Looks sixteen at least," said the

superintendent.

"Or sixty," snapped the inspector.

"He's always looked that way."

"How long?" asked the inspector

quickly.

"For years. Never gets a bit

older."

"Or younger, I daresay. I suppose he's

worked here all those years?"

"Off and on—but that was before the new law

was passed," the superintendent hastened to add.

"Machine idle?" the inspector asked,

pointing at the unoccupied machine beside Johnny's, in which the part-filled

bobbins were flying like mad.

"Looks that way." The superintendent

motioned the overseer to him and shouted in his ear and pointed at the machine.

"Machine's idle," he reported back to the inspector.

They passed on, and Johnny returned to his work,

relieved in that the ill had been averted. But the one-legged boy was not so

fortunate. The sharp-eyed inspector haled him out at arm's length from the

bin-truck. His lips were quivering, and his face had all the expression of one

upon whom was fallen profound and irremediable disaster. The overseer looked

astounded, as though for the first time he had laid eyes on the boy, while the

superintendent's face expressed shock and displeasure.

"I know him," the inspector said.

"He's twelve years old. I've had him discharged from three factories

inside the year. This makes the fourth."

He turned to the boy. "You promised me, word

and honor, that you'd go to school."

The one-legged boy burst into tears.

"Please, Mr. Inspector, two babies died on us, and we're awful

poor."

"What makes you cough that way?" the

inspector demanded, as though charging him with crime.

And as in denial of guilt, the one-legged boy

replied, "It ain't nothin'. I jes' caught a cold last week, Mr. Inspector,

that's all."

In the end the one-legged boy went out of the

room with the inspector, the latter accompanied by the anxious and protesting

superintendent. After that monotony settled down again. The long morning and

the longer afternoon wore away while the whistle blew for quitting-time.

Darkness had already fallen when Johnny passed out through the factory gate. In

the interval the sun had made a golden ladder of the sky, flooded the world

with its gracious warmth, and dropped down and disappeared in the west behind a

ragged sky-line of housetops.

Supper was the family meal of the day—the one

meal at which Johnny encountered his younger brothers and sisters. It partook

of the nature of an encounter, to him, for he was very old, while they were

distressingly young. He had no patience with their excessive and amazing

juvenility. He did not understand it. His own childhood was too far behind him.

He was like an old and irritable man, annoyed by the turbulence of their young

spirits that was to him arrant silliness. He glowered silently over his food,

finding compensation in the thought that they would soon have to go to work.

That would take the edge off of them and make them sedate and dignified—like

him. This it was, after the fashion of the human, that Johnny made of himself a

yardstick with which to measure the universe.

During the meal, his mother explained in various

ways and with infinite repetition that she was trying to do the best she could;

so that it was with relief, the scant meal ended, that Johnny shoved back his

chair and arose. He debated for a moment between bed and the front door, and

finally went out the latter. He did not go far. He sat down on the stoop, his

knees drawn up and his narrow shoulders drooping forward, his elbows on his

knees and the palms of his hands supporting his chin.

As he sat there he did no thinking. He was just

resting. So far as his mind was concerned it was asleep. His brothers and

sisters came out, and with other children played noisily about him. An electric

globe on the corner lighted their frolics. He was peevish and irritable, that

they knew; but the spirit of adventure lured them into teasing him. They joined

hands before him, and, keeping time with their bodies, chanted in his face

weird and uncomplimentary doggerel. At first he snarled curses at them—curses

he had learned from the lips of various foremen. Finding this futile, and

remembering his dignity, he relapsed into dogged silence.

His brother Will, next to him in age, having just

passed his tenth birthday, was the ringleader. Johnny did not possess

particularly kindly feelings toward him. His life had early been embittered by

continual giving over and giving way to Will. He had a definite feeling that

twill was greatly in his debt and was ungrateful about it. In his own playtime,

far back in the dim past, he had been robbed of a large part of that playtime

by being compelled to take care of Will. Will was a baby then, and then as now

their mother had spent her days in the mills. To Johnny had fallen the part of

little father and little mother as well.

Will seemed to show the benefit of the giving

over and the giving way. He was well-built, fairly rugged, as tall as his elder

brother and even heavier. It was as though the life-blood of the one had been

diverted into the other's veins. And in spirits it was the same. Johnny was

jaded, worn out, without resilience, while his brother seemed bursting and

spilling over with exuberance.

The mocking chant rose louder and louder. Will

leaned closer as he danced, thrusting out his tongue. Johnny's left arm shot

out and caught the other around the neck. At the same time he rapped his bony

fist to the other's nose. It was a pathetically bony fist, but that it was

sharp to hurt was evidenced by the squeal of pain it produced. The other

children were uttering frightened cries, while Johnny's sister, Jennie, had

dashed into the house.

He thrust Will from him, kicked him savagely on

the shins, then reached for him and slammed him face downward in the dirt. Nor

did he release him till the face had been rubbed into the dirt several times.

Then the mother arrived, an anemic whirlwind of solicitude and maternal

wrath.

"Why can't he leave me alone?" was

Johnny's reply to her upbraiding. "Can't he see I'm tired?"

"I'm as big as you," Will raged in her

arms, his face a mess of tears, dirt and blood. "I'm as big as you now,

an' I'm goin' to git bigger. Then I'll lick you—see if I don't."

"You ought to be to work, seein' how big you

are," Johnny snarled. "That's what's the matter with you. You ought

to be to work. An' it's up to your ma to put you to work."

"But he's too young," she protested.

"He's only a little boy."

"I was younger'n him when I started to

work."

Johnny's mouth was open, further to express the

sense of unfairness that he felt, but the mouth closed with a snap. He turned

gloomily on his heel and stalked into the house and to bed. The door of his

room was open to let in warmth from the kitchen. As he undressed in the

semi-darkness he could hear his mother talking with a neighbor woman who had

dropped in. His mother was crying, and her speech was punctuated with

spiritless sniffles.

"I can't make out what's gittin' into

Johnny," He could hear her say. "He didn't used to be this way. He

was a patient little angel.

"An' he is a good boy," she

hastened to defend. "He's worked faithful, an' he did go to work too

young. But it wasn't my fault. I do the best I can, I'm sure."

Prolonged sniffling from the kitchen, and Johnny

murmured to himself as his eyelids closed down, "You betcher life I've

worked faithful."

The next morning he was torn bodily by his mother

from the grip of sleep. Then came the meager breakfast, the tramp through the

dark, and the pale glimpse of day across the housetops as he turned his back on

it and went in through the factory gate. It was another day, of all the days,

and all the days were alike.

And yet there had been variety in his life—at

the times he changed from one job to another, or was taken sick. When he was

six he was little mother and father to Will and the other children still

younger. At seven he went into the mills—winding bobbins. When he was eight he

got work in another mill. His new job was marvelously easy. All he had to do

was to sit down with a little stick in his hand and guide a stream of cloth

that flowed past him. This stream of cloth came out of the maw of a machine,

passed over a hot roller, and went on its way elsewhere. But he sat always in

the one place, beyond the reach of daylight, a gas-jet flaring over him,

himself part of the mechanism.

He was very happy at that job, in spite of the

moist heat, for he was still young and in possession of dreams and illusions.

And wonderful dreams he dreamed as he watched the steaming cloth streaming

endlessly by. But there was no exercise about the work, no call upon his mind,

and he dreamed less and less, while his mind grew torpid and drowsy.

Nevertheless, the earned two dollars a week, and two dollars represented the

difference between acute starvation and chronic underfeeding.

But when he was nine, he lost his job. Measles

was the cause of it. After he recovered he got work in a glass factory. The pay

was better, and the work demanded skill. It was piece-work, and the more

skilful he was the bigger wages he earned. Here was incentive. And under this

incentive he developed into a remarkable worker.

It was simple work, the tying of glass stoppers

into small bottles. At his waist he carried a bundle of twine. He held the

bottles between his knees so that he might work with both hands. Thus, in a

sitting position and bending over his own knees, his narrow shoulders grew

humped and his chest was contracted for ten hours each day. This was not good

for the lungs, but he tied three hundred dozen bottles a day.

The superintendent was very proud of him, and

brought visitors to look at him. It ten hours three hundred dozen bottles

passed through his hands. This meant that he had attained machine-like

perfection. All waste movements were eliminated. Every motion of his thin arms,

every movement of a muscle in the thin fingers, was swift and accurate. He

worked at high tension, and the result was that he grew nervous. At night his

muscles twitched in his sleep, and in the daytime he could not relax and rest.

He remained keyed up and his muscles continued to twitch. Also he grew sallow

and his lint-cough crew worse. Then pneumonia laid hold of the feeble lungs

within the contracted chest, and he lost his job in the glass-works.

Now he had returned to the jute-mills, where he

had first begun with the winding bobbins. But promotion was waiting for him. He

was a good worker. He would next go on the starcher, and later he would go into

the loom-room. There was nothing after that except increased efficiency.

The machinery ran faster than when he had first

gone to work, and his mind ran slower. He no longer dreamed at all, though his

earlier years had been full of dreaming. Once he had been in love. It was when

he first began guiding the cloth over the hot roller, and it was with the

daughter of the superintendent. She was much older than he, a young woman, and

he had seen her at a distance a paltry half dozen times. But that made no

difference. On the surface of the cloth stream that poured past him, he

pictured radiant futures wherein he performed prodigies of toil, invented

miraculous machines, won to the mastership of the mills, and in the end took

her in his arms and kissed her somberly on the brow.

But that was all in the long ago, before he had

grown too old and tired to love. Also, she had married and gone away, and his

mind had gone to sleep. Yet it had been a wonderful experience, and he used

often to look back upon it as other men and women look back upon the time they

believed in fairies. He had never believed in fairies nor Santa Claus; but he

had believed implicitly in the smiling futures his imagination had wrought into

the steaming cloth stream.

He had become a man very early in life. At seven,

when he drew his first wages, began his adolescence. A certain feeling of

independence crept up in him, and the relationship between him and his mother

changed. Somehow, as an earner and bread-winner, doing his own work in the

world, he was more like an equal with her. Manhood, full-blown manhood, had

come when he was eleven, at which time he had gone to work on the night-shift

for six months. No child works on the night-shift and remains a child.

There had been several great events in his life.

One of these had been when his mother bought some California prunes. Two others

had been the two times when she cooked custard. Those had been events. He

remembered them kindly. And at that time his mother had told him of a blissful

dish she would sometime make—"floating island," she had called it,

"better than custard." For years he looked forward to the day when he

would sit down to the table with floating island before him, until at last he

had relegated the idea of it to the limbo of unattainable ideals.

Once he found a silver quarter lying on the

sidewalk. That, also, was a great event in his life, withal a tragic one. He

knew his duty on the instant the silver flashed on his eyes, before even he had

picked it up. At home, as usual, there was not enough to eat, and home he

should have taken it as he did his wages every Saturday night. Right conduct in

this case was obvious; but he never had any spending of his money, and he was

suffering from candy-hunger. He was ravenous for the sweets that only on

red-letter days he had ever tasted in his life.

He did not attempt to deceive himself. He knew it

was sin, and deliberately he sinned when he went on a fifteen-cent candy

debauch. Ten cents he saved for a future debauch; but not being accustomed to

the carrying of money, he lost the ten cents. This occurred at the time when he

was suffering all the torments of conscience, and it was to him and act of

divine retribution. He had a frightened sense of the closeness of an awful and

wrathful God. God had seen, and God had been swift to punish, denying him even

the full wages of sin.

In memory he always looked back upon that event

as the one great criminal deed of his life, and at the recollection his

conscience always awoke and gave him another twinge. It was the one skeleton in

his closet. Also, being so made and circumstanced, he looked back upon the deed

with regret. He was dissatisfied with the manner in which he had spent the

quarter. He could have invested it better, and, out of his later knowledge of

the quickness of God, he would have beaten God out by spending the whole

quarter at one fell swoop. In retrospect he spent the quarter a thousand times

and each time to better advantage.

There was one other memory of the past, dim and

faded, but stamped into his soul everlastingly by the savage feet of his

father. It was more like a nightmare than a remembered vision of a concrete

thing—more like the race-memory of man that makes him fall in his sleep and

that goes back to his arboreal ancestry.

This particular memory never came to Johnny in

broad daylight when he was wide awake. It came at night, in bed, at the moment

that his consciousness was sinking down and losing itself in sleep. It always

aroused him to frightened wakefulness, and for the moment, in the first

sickening start, it seemed to him that he lay crosswise on the foot of the bed.

In the bed were the vague forms of his father and mother. He never saw what his

father looked like. He had but on impression of his father, and that was that

he had savage and pitiless feet.

His earlier memories lingered with him, but he

had no late memories. All days were alike. Yesterday or last year were the same

as a thousand years—or a minute. Nothing ever happened. There were no events

to mark the march of time. Time did not march. It stood always still. It was

only the whirling machines that moved, and they moved nowhere—in spite of the

fact that they moved faster.

When he was fourteen he went to work on the

starcher. It was a colossal event. Something had at last happened that could be

remembered beyond a night's sleep or a week's pay-day. It marked an era. It was

a machine Olympiad, a thing to date from. "When I went to work on the

starcher," or, "after," or "before I went to work on the

starcher," were sentences often on his lips.

He celebrated his sixteenth birthday by going

into the loom-room and taking a loom. Here was an incentive again, for it was

piece-work. And he excelled, because the clay of him had been molded by the

mills into the perfect machine. At the end of three months he was running two

looms, and, later, three and four.

At the end of his second year at the looms, he

was turning out more yards than any other weaver, and more than twice as much

as some of the less skilful ones. And at home things began to prosper as he

approached the full stature of his earning power. Not, however, that his

increased earnings were in excess of need. The children were growing up. They

ate more. And they were going to school, and school-books cost money. And

somehow, the faster he worked, the faster climbed the prices of things. Even

the rent went up, though the house had fallen from bad to worse disrepair.

He had grown taller; but with his increased

height he seemed leaner than ever. Also, he was more nervous. With the

nervousness increased his peevishness and irritability. The children had

learned by many bitter lessons to fight shy of him. His mother respected him

for his earning power, but somehow her respect was tinctured with fear.

There was no joyousness in life for him.  The procession

of the days he never saw. The nights he slept away in twitching

unconsciousness. The rest of the time he worked, and his consciousness was

machine consciousness. Outside this his mind was a blank. He had no ideals, and

but one illusion, namely, that he drank excellent coffee. He was a work-beast.

He had no mental life whatever; yet deep down in the crypts of his mind,

unknown to him, were being weighted and sifted every hour of his toil, every

movement of his hands, every twitch of his muscles, and preparations were

making for a future course of action that would amaze him and all his little

world.

The procession

of the days he never saw. The nights he slept away in twitching

unconsciousness. The rest of the time he worked, and his consciousness was

machine consciousness. Outside this his mind was a blank. He had no ideals, and

but one illusion, namely, that he drank excellent coffee. He was a work-beast.

He had no mental life whatever; yet deep down in the crypts of his mind,

unknown to him, were being weighted and sifted every hour of his toil, every

movement of his hands, every twitch of his muscles, and preparations were

making for a future course of action that would amaze him and all his little

world.

It was in the late spring that he came home from

work one night aware of an unusual tiredness. There was a keen expectancy in

the air as he sat down to the table, but he did not notice. He went through the

meal in moody silence, mechanically eating what was before him. The children

um'd and ah'd and made smacking noises with their mouths. But he was deaf to

them.

"D'ye know what you're eatin'?" his

mother demanded at last, desperately.

He looked vacantly at the dish before him, and

vacantly at her.

"Floatin' island," she announced

triumphantly.

"Oh," he said.

"Floatin' island!" the children

chorused loudly.

"Oh," he said. And after two or three

mouthfuls, he added, "I guess I ain't hungry to-night."

He dropped the spoon, shoved back his chair, and

arose wearily from the table.

"An' I guess I'll go to bed."

His feet dragged more heavily than usual as he

crossed the kitchen floor. Undressing was a Titan's task, a monstrous futility,

and he wept weakly as he crawled into bed, one shoe still on. He was aware of a

rising, swelling something inside his head that made his brain thick and fuzzy.

His lean fingers felt as big as his wrist, while in the ends of them was a

remoteness of sensation vague and fuzzy like his brain. The small of his back

ached intolerably. All his bones ached. He ached everywhere. And in his head

began the shrieking, pounding, crashing, roaring of a million looms. All space

was filled with flying shuttles. They darted in and out, intricately, amongst

the stars. He worked a thousand looms himself, and ever they speeded, faster

and faster, and his brain unwound, faster and faster, and became the thread

that fed the thousand flying shuttles.

He did not go to work the next morning. He was

too busy weaving colossally on the thousand looms that ran inside his head. His

mother went to work, but first she sent for the doctor. It was a severe attack

of la grippe, he said. Jennie served as nurse and carried out his

instructions.

It was a very severe attack, and it was a week

before Johnny dressed and tottered feebly across the floor. Another week, the

doctor said, and he would be fit to return to work. The foreman of the

loom-room visited him on Sunday afternoon, the first day of his convalescence.

The best weaver in the room, the foreman told his mother. His job would be held

for him. He could come back to work a week from Monday.

"Why don't you thank 'm, Johnny?" his

mother asked anxiously.

"He's ben that sick he ain't himself

yet," she explained apologetically to the visitor.

Johnny sat hunched up and gazing steadfastly at

the floor. He sat in the same position long after the foreman had gone. It was

warm outdoors, and he sat on the stoop in the afternoon. Sometimes his lips

moved. he seemed lost in endless calculations.

Next morning, after the day grew warm, he took

his seat on the stoop. He had pencil and paper this time with which to continue

his calculations, and he calculated painfully and amazingly.

"What comes after millions?" he asked

at noon, when Will came home from school. "An' how d'ye work

'em?"

That afternoon finished his task. Each day, but

without paper and pencil, he returned to the stoop. He was greatly absorbed in

the one tree that grew across the street. He studied it for hours at a time,

and was unusually interested when the wind swayed its branches and fluttered

its leaves. Throughout the week he seemed lost in a great communion with

himself. On Sunday, sitting on the stoop, he laughed aloud, several times, to

the perturbation of his mother, who had not heard him laugh in years.

Next morning, in the early darkness, she came to

his bed to rouse him. He had had his fill of sleep all week and awoke easily.

He made no struggle, nor did he attempt to hold on to the bedding when she

stripped it from him. He lay quietly, and spoke quietly.

"It ain't no use, ma."

"You'll be late," she said, under the

impression that he was still stupid with sleep.

"I'm awake, ma, an' I tell you it ain't no

use. You might was well lemme alone. I ain't goin' to git up."

But you'll lose your

job!" she cried.

"I ain't goin' to git up," he repeated

in a strange, passionless voice.

She did not go to work herself that morning. This

was sickness beyond any sickness she had ever known. Fever and delirium she

could understand; but this was insanity. She pulled the bedding up over him and

sent Jennie for the doctor.

When that person arrived Johnny was sleeping

gently, and gently he awoke and allowed his pulse to be taken.

"Nothing the matter with him," the

doctor reported. "Badly debilitated, that's all. Not much meat on his

bones."

"He's always been that way," his mother

volunteered.

"Now go 'way, ma, an' let me finish my

snooze."

Johnny spoke sweetly and placidly, and sweetly

and placidly he rolled over on his side and went to sleep.

At ten o'clock he awoke and dressed himself. He

walked out into the kitchen, where he found his mother with a frightened

expression on her face.

"I'm goin' away, ma," he announced,

"an' I jes' want to say good-by."

She threw her apron over her head and sat down

suddenly and wept. He waited patiently.

"I might a-known it," she was

sobbing.

"Where?" she finally asked, removing

the apron from her head and gazing up at him with a stricken face in which

there was little curiosity.

"I don't know—anywhere."

As he spoke the tree across the street appeared

with dazzling brightness on his inner vision. It seemed to lurk just under his

eyelids, and he could see it whenever he wished.

"An' your job?" she quavered.

"I ain't never goin' to work

again."

"My God, Johnny!" she wailed,

"don't say that!"

What he had said was blasphemy to her. As a

mother hears her child deny God, was Johnny's mother shocked by his words.

"What's got into you, anyway?" she

demanded, with a lame attempt at imperativeness.

"Figures," he answered. "Jes'

figures. I've ben doin' a lot of figurin' this week, an' it's most

surprisin'."

"I don't see what that's got to do with

it," she sniffled.

Johnny smiled patiently, and his mother was aware

of a distinct shock at the persistent absence of his peevishness and

irritability.

"I'll show you," I said. "I'm plum

tired out. What makes me tired? Moves. I've ben movin' ever since I was born.

I'm tired of movin', an' I ain't goin't to move any more. Remember when I

worked in the glass-house? I used to do three hundred dozen a day. Now I reckon

I made about ten different moves to each bottle. That's thirty-six thousan'

moves a day. Ten days, three hundred an' sixty thousan' moves. One month, one

million an' eighty thousan' moves. Chuck out the eighty thousan'—" he

spoke with the complacent beneficence of a philanthropist—"chuck out the

eighty thousan', that leaves a million moves a month—twelve million moves a

year.

"And the looms I'm movin' twic'st as much.

That makes twenty-five million moves a year, an' it seems to me I've ben

a-movin' that way 'most a million years.

"Now this week I ain't moved at all. I ain't

made one move in hours an' hours. I tell you it was swell, jes' settin' there,

hours an' hours, an' doin' nothin'. I ain't never ben happy before. I never had

any time. I've ben movin' all the time. That ain't no way to be happy. An' I

ain't goin' to do it any more. I'm jes' goin' to set, an' set, an' rest, an'

rest, an' then rest some more."

"But what's goin' to come of Will an' the

childern?" she asked despairingly.

"That's it, 'Will an' the childern,'"

he repeated.

But there was no bitterness in his voice. He had

long known his mother's ambition for the younger boy, but the thought of it no

longer rankled. Nothing mattered any more. Not even that.

"I know, ma, what you've ben plannin' for

Will—keepin' him in school to make a bookkeeper out of him. But it ain't know

use. I've quit. He's got to go to work."

"An' after I have brung you up the way I

have," she wept, starting to cover her head with the apron and changing

her mind.

"You never brung me up," he answered

with sad kindliness. "I brung myself up, ma, an' I brung up Will. He's

bigger'n me, an' heavier, an' taller. When I was a kid I reckon I didn't git

enough to eat. When he come along an' was a kid, I was workin' an' earnin' grub

for him, too. But that's done with. Will can go to work, same as me, or he can

go to hell, I don't care which. I'm tired. I'm goin' now. Ain't you goin' to

say good-by?"

She made no reply. The apron had gone over her

head again and she was crying. He paused a moment in the doorway.

"I'm sure I done the best I knew how,"

she was sobbing.

He passed out of the house and down the street. A

wan delight came into his face at the sight of the lone tree. "Jes' ain't

goin' to do nothin'," He said to himself, half aloud, in a crooning tone.

He glanced wistfully up at the sky, but the bright sun dazzled and blinded

him.

It was a long walk he took, and he did not walk

fast. It took him past the jute-mill. The muffled roar of the loom-room came to

his ears, and he smiled. It was a gentle, placid smile. He hated no one, not

even the pounding, shrieking machines. There was no bitterness in him, nothing

but an inordinate hunger for rest.

The houses and factories thinned out and the open

spaces increased as he approached the country. At last the city was behind him,

and he was walking down a leafy lane beside the railroad track. He did not walk

like a man. He did not look like a man. He was a travesty of the human. It was

a twisted and stunted and nameless piece of life that shambled like a sickly

ape, arms loose-hanging, stoop-shouldered, narrow-chested, grotesque and

terrible.

He passed by a small railroad station and lay

down in the grass under at tree. All afternoon he lay there. Sometimes he

dozed, with muscles that twitched in his sleep. When awake, he lay without

movement, watching the birds or looking up at the sky through the branches of

the tree above him. Once or twice he laughed aloud, but without relevance to

anything he had seen or felt.

After twilight had gone, in the first darkness of

the night, a freight train rumbled into the station. While the engine was

switching cars onto the side-track, Johnny crept along the side of the train.

He pulled open the side-door of an empty box-car and awkwardly and laboriously

climbed in. He closed the door. The engine whistled. Johnny was lying down, and

in the darkness he smiled.

Back to the Jack London index.