Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() N ALL the long red history of war, disease has stalked at the heels

of armies. In the present generation it bids fair to cease stalking, at least

at the heels of armies that are scientifically and modernly handled. I have

just been studying the mortality statistics of Vera Cruz for the last sixteen

months. There is a peculiar blank space at the head of the column marked

"Cerebro-spinal Meningitis." For the first six months of 1913 there

were no deaths from meningitis. In July there were three deaths. By December,

in that month alone, there were twenty deaths. The abrupt appearance of this

disease led me to inquire of Major F. M. Hartsock for an explanation.

N ALL the long red history of war, disease has stalked at the heels

of armies. In the present generation it bids fair to cease stalking, at least

at the heels of armies that are scientifically and modernly handled. I have

just been studying the mortality statistics of Vera Cruz for the last sixteen

months. There is a peculiar blank space at the head of the column marked

"Cerebro-spinal Meningitis." For the first six months of 1913 there

were no deaths from meningitis. In July there were three deaths. By December,

in that month alone, there were twenty deaths. The abrupt appearance of this

disease led me to inquire of Major F. M. Hartsock for an explanation.

The appearance of meningitis in Vera Cruz seems

to have been due to Mexico's customary way of doing business. From far up to

the north a drove of Constitutionalist prisoners, infected with meningitis, was

sent south. They were moved right along. No one in authority cared to segregate

them and stamp out the disease. This wretched drove became a perambulating

plague. It was a case, in poker parlance, of "passing the buck."

At last they arrived in Mexico City, where they

promptly infected their prison. Again the buck was passed, and they were

shipped on to Vera Cruz. I do not possess the date of their arrival in the

latter city, but it is patent that it must have been some time in July, 1913,

at which date the death figures suddenly appear in the meningitis column.

There seems to have been no further place to

which to pass them along, so they were finally segregated in prison. From the

first to the twentieth of April, 1914, there were six deaths from meningitis.

It was about this time that the American forces landed and took possession of

Vera Cruz, while General Maas, his soldiers, and released prisoners took to the

brush. And they took their meningitis with them, for there has not been a case

of it since in Vera Cruz.

Conquering the Grisly Monster, Typhoid

WHAT

the adventures of this meningitis will be now that it has again

gone wandering may be imagined. The very clothing of these men, as well as

themselves, is saturated with meningitis, and that they will spread the

infection cannot be doubted. At any rate, the times have changed, for the

disease left town with old-fashioned war when modern war marched in.

Smallpox appears to be endemic, rather than

epidemic, in Vera Cruz, while tuberculosis, strange to say, collects a greater

toll of death than all the more serious diseases added together. Here, in the

tierras calientes, or hot lands, where it is so continuously warm that

in a room flung wide to the outer air and every vagrant breeze even a sheet

over one at night is suffocating, the natives crowd into small, unventilated

rooms, weaken their lungs, and fall victims to the White Plague. Malaria, also,

is a never-absent disease, the death line of it rising rhythmically in the

rainy season and falling in the dry season. It, too, by its weakening effect on

its victims, is the cause of their contracting other diseases from which they

perish, chiefest of which, of course, is tuberculosis.

But our army surgeons, wise in tropical diseases

from their service in Cuba, Porto Rico, Panama, and the Philippines, are not

apprehensive of any grave epidemics in Mexico. They have learned much and

rapidly in the last decade and a half, and what they have learned is

demonstrable by statistics.

Typhoid has ever been a grisly monster to north

European and American armies. The Latins and the Asiatics are more immune, this

being doubtless due to a rigid selection, operating through many centuries, by

which typhoid killed off all that were predisposed to typhoid. Thus, whenever

men are gathered together in armies, there will be found a far greater

proportion of nonimmunes among the north Europeans and Americans than among the

Latins and Asiatics.

In 1898, in Florida, the United States mobilized

12,000 men for a period of four months. During this time there were 2,600 cases

of typhoid and 480 deaths from typhoid. Nor is this the whole story. The

soldiers carried the disease with them into Cuba, where many another death

resulted from the four months spent in Florida.

The Weapons—Sanitation and Vaccination

IN 1911, in San Antonio, Tex., 12,000 soldiers were mobilized for four months. During this period there were two cases of typhoid and no deaths. In 1913 and 1914, at Texas City and Galveston, 12,000 soldiers were in camp for many months, during which there was not a single death from typhoid nor a single case of typhoid. In this last long mobilization all other infectious diseases were practically negligible. In the year 1913, in the entire army of the United States, whether stationed at home, in Panama, Hawaii, or the Philippines, there were only six cases of typhoid. This remarkable record, covering so brief a period of time, has been made possible by two things: first, the education of soldiers in camp sanitation and personal hygiene; and, second, the inoculation, or vaccination, of the soldiers against typhoid.

Uncle Sam's Sure Method

THE

United States was the first country to inoculate its soldiers and

sailors against typhoid, and it is safe to assume, no matter in what other ways

its soldiers may lose their lives in Mexico, that none will die from typhoid.

The serum is hypodermically injected into the arm in a series of three

injections, the intervals between injections being ten days. In a way, the

injectee becomes a sort of peripatetic graveyard. The first injection puts

into his blood the nicely dead carcasses of some 500,000,000 microorganisms

along with all their virtues of deadness which bring about a change in the

constitution of the blood that makes it resistant to future invasions of

full-powered, malignant typhoid microorganisms. With this first injection,

theoretically, the man has had reduced the 100 per cent of his nonimmunity to

typhoid to 32 per cent.

The second injection, ten days later, consists of

a thousand million nicely dead carcasses of the disease. Also, it reduces his

nonimmunity to 8 per cent. The third injection introduces another billion of

the same ably efficient carcasses, and reduces his nonimmunity to zero. In

short, when his body has become the living cemetery of half a billion more dead

bodies that there are live humans in all the world, he has become so noxious to

the particularly noxious and infective typhoid that he may be classed a

positive immune.

No Indisposition from Inoculation

IT

IS very easy, the actual process of inoculation. I have had the

pleasure of reducing my nonimmunity of 100 per cent to zero per cent. The first

inoculation was perpetrated in a transport hospital, the second in a captured

academy turned into an army hospital, the third in a field hospital. The stab

of the hypodermic syringe, different from the manner of administering morphine

just under the skin, goes straight down and squarely down into the meat of the

arm for half an inch; but the pang of the stab is no severer. The hurt of the

stab is over the instant the skin is punctured. It is only the nerves of the

skin that protest in either case.

After an inoculation there is no indisposition.

The arm is a trifle sore for several days, and that is all. Some inoculates

aver that they awaken from the first night's sleep with a dark brown taste in

their mouths. In rare cases a mild increase of temperature is noted, reaching

its height some six hours after the inoculation and fading quickly away. I have

talked with a daring one who took the total quantity at one time, and who

stated that the impact was equivalent to a man's fist between the eyes and that

he was not quite himself again for all of twenty-four hours.

But the big thing about the whole affair is the statistics. Individuals do not count. What counts is the results achieve by the inoculation of thousands of men. What counts is the reduction to nothing of typhoid cases in the army hospitals. What counts is the reduction to nothing of the army funerals due to typhoid. Modern war of men against men on the field of battle is now preceded by microorganic wars on the part of our surgeons before ever our men depart for the front. And, Heavens, what tremendous wars are waged by the surgeons! The mortality stuns one when endeavoring to contemplate its totality. When two billion five hundred million microorganisms are slain merely to make one soldier immune against one disease, the sum total of slain microorganisms for a whole army is much beyond mere human conception as the entire visible sidereal system along with what is invisible outside of it. Yet there can be no discussion of the efficacy of inoculation against typhoid. The morbidity and mortality tables of our large-scale army experiments tell the incontrovertible tale.

Surgeon Pioneers

NO

HEALTHY recruit, having successfully passed the rigid physical

examination, is any longer permitted immediately to join the organization to

which he is allotted. Healthy recruits have a way of coming down with all sorts

of diseases as soon as they change their environment, particularly with

measles, mumps, diphtheria, whooping cough, and scarlet fever. In the old days

so recent, before it was understood, the recruits spread these diseases among

the regiments they joined.

But to-day, ere they are received into the ranks

of their company and regiment, no matter how healthy they may be at the time,

they are forced first to undergo twelve days of isolation. In this phase, the

clean record of the Texas City and Galveston mobilization in such simple

diseases exceeded the record of the previous mobilization at San Antonio. While

all this is a very recent practice, it is a practice wider spread than the

army. No scientific hog breeder to-day, whether importing a prize boar from

another State, another country, or another farm, is rash enough immediately to

turn it in with his herd. It must first undergo its quarantine in a segregated

part of the farm.

The army surgeons to-day are our foreloopers and

pioneers. Not only do they stay at home with the army and make it fit, but they

scout ahead of the army so that its fitness my continue in strange lands and

places. They gather the data on the diseases prevalent in all countries, and

their battles and campaigns are planned and mapped and ready to be fought on an

instant's notice, no matter to what intersection of latitude and longitude the

army may be summoned.

So it is, first, that every soldier up to the

present moment landed in Mexico is free of all disease and immune to such

diseases as smallpox and typhoid; and, second, that a complete and better body

of data has been gathered by our surgeons on diseases in Mexico than has been

gathered by the Mexican Government. Our men start uninfected with a fair

promise of escaping infection when they tread Mexican soil.

Thanks to our discoveries in Cuba some years ago

regarding yellow fever, Vera Cruz was cleaned up. Hitherto, along with Panama

(since cleaned up by us), it ranked with Guayanquil as one of the three plague

ports of the New World. Remains Guayaquil—still revolutionizing—as great a

yellow fever pesthole as ever. We have cleared yellow fever out of Panama, and

it is to be doubted if a single case of yellow fever shows itself among our

troops in Vera Cruz.

The Petrolero to the Front

YELLOW

fever is so simple a thing to manage. Yet we paid a terrible

death penalty for our ignorance through all the centuries down to just the

other day. We know now that a certain breed of mosquito is the only carrier of

the disease. We know that the way such a mosquito becomes infected is by biting

a human being who is stricken with yellow fever. We know that only in the first

three days that a human being is so stricken is it possible for the uninfected

mosquito to become infected.

The remedy, or rather the preventive, is equally

simple. First, wire screen the yellow fever patient so that no mosquitoes may

be infected by him. Second, fumigate the house in which he lies so that no

possibly infected mosquitoes therein may infect other humans. Third, and purely

a prevision, destroy all mosquitoes in the neighborhood.

In the days of the Paris Commune the

petroleur flourished. To-day, in the American armies on service in the

tropics, the petrolero flourishes. He is the man who spreads oil on all

stagnant waters. The larva of the mosquito cannot hatch in running water, nor

in fish-inhabited water. But it can hatch in a sardine can or in the depression

made by a cow's hoof in soft soil when such receptacles are filled with rain

water.

Not content with their own tropical experience,

our army surgeons in Vera Cruz are reinforced by such experts from the Marine

Hospital Service as G. M. Guiteras and Rudolph von Ezdorf, who have taken

charge of the public health of this one-time death hole of Vera Cruz.

Killing two birds with one stone, or performing two actions with one movement, is a joy forever and cuts down the overhead. It so happens that the same preventative measures for yellow fever are preventative of malaria. Every wire screen about a patient, every drop of oil on the surface of standing water, performs the double duty. Further, purely as a prophylactic measure, each soldier will receive a determined number of grains of quinine daily until such time that Vera Cruz has been metamorphosed into a health resort.

Putting the Taxes at Hones Work

THE

authorities at Vera Cruz did not know as much about their own

water supply as did our army surgeons before our expedition started. They knew

that the source of the water supply, the Jamapa River, was a fast-flowing

stream and uncontaminated. Also, to make doubly sure, they were in possession

of analyses of the water.

Amebic dysentery is of rare occurrence in Vera

Cruz. Smallpox is no longer a thing of which to be afraid. And, further, most

of it seems to have deserted Vera Cruz along with General Maas and his

soldiers.

The United States is large. The

United States army is small. It is scattered here and there in army posts. The

average citizen knows less of his own army than he knows of north and south

polar exploration. As regards the duties and activities of the army surgeons he

does not dream of anything beyond the fact that they keep the soldiers well in

time of peace, and in war dress wounds and amputate limbs. It would make him

sit up and take notice if he could see how complex and multifarious are their

activities here in Vera Cruz.

The United States is large. The

United States army is small. It is scattered here and there in army posts. The

average citizen knows less of his own army than he knows of north and south

polar exploration. As regards the duties and activities of the army surgeons he

does not dream of anything beyond the fact that they keep the soldiers well in

time of peace, and in war dress wounds and amputate limbs. It would make him

sit up and take notice if he could see how complex and multifarious are their

activities here in Vera Cruz.

To commence with, the army is not their only

problem. To keep the army well, they must keep the city well. Not only must

they attend to their own sick and wounded, but they must attend to the sick and

wounded of the Mexican populace and army hospitals, public hospitals, charity

hospitals, women's hospitals, and orphan asylums. Now Uncle Sam is somewhat

meager in such matters. The people of Vera Cruz supported these institutions

before, says Uncle Sam. Therefore, make Vera Cruz support them again. Do you

think I am spending my money like a drunken sailor? Uncle Sam concludes

indignantly.

And our surgeons go and do it, though it takes

all the rest of the army to help. Vera Cruz must pay for those institutions.

But these institutions are two months behind in their bills and salaries, and

there is no money in the city treasury. The last was clean looted by the

officials who had charge of it. Army officers are told off to handle the

collection of taxes. So far as the Vera Cruzan taxpayer is concerned, the taxes

are as they always were. But for the first time in the history of Vera Cruz the

taxes are expended without graft for public service. The back bills and

salaries are paid, and the future bills and salaries are guaranteed.

Hosplitals First

THE

hotels and cantinas are crowded with thirsty refugees, soldiers,

sailors, and foreign guests, all with a penchant for long, cool drinks. More

ice than ordinarily is consumed. The ice plant is a private enterprise. Its

output is limited. There is not enough to go around. Hotels and cantinas are

cash buyers and pay a premium for ice. Result: (a) the hospitals are

skimped in ice; (b) the surgeons make the suggestion and the army takes

charge of the ice plant, supplying the hospitals first and letting the hotels

and cantinas have what is left.

The naval authorities have already taken

possession of the island and lazaretto Sacrificios, just outside the port of

Vera Cruz. There is no yellow fever at present, but if a sporadic case should

appear, Sacrificios is just the place to segregate it.

I was in the field hospital just after an

operation for appendicitis had been performed on one of our officers. In old

San Sebastian Hospital lie many of the sick of the city and many of the

soldiers that General Maas left behind to fight from the housetops. Many

amputations had been performed, and more were being performed.

Also, I watched the dressing of the wounds of

these poor Federals, and want to register my protest right now that modern war,

for the man who gets bullet wounded, is not at all as romantic as old time war.

Furthermore, a modern bullet, despite its steel jacket which keeps it from

spreading, is a terrifically disruptive thing to have introduced into one's

body. I would far prefer being struck with an old-time bullet than with a

modern one.

It seems that the flight or our long,

sharp-nosed, lean, cylindrical, modern bullet is divided into three flights

much as the spinning of a top is divided into three spins. When first a top is

spun, it jumps and bounces, and bounds about in an erratic way. After a time it

attains equilibrium. This is its mid-spin. It makes no perceptible movement,

and to the eye seems stationary and dead. It is this stage that the small boy

calls "sleeping." Then comes its last spin. It bounds and wobbles

about as it loses the last of its momentum, and it finally lies down on its

side and is dead.

Sleeping and Wobbling Bullets

ALMOST

precisely the same thing occurs with the modern bullet. Its

first flight is something like seven hundred yards. During this period, like

the top, it is erratic. It wobbles. If it hits anything while it is wobbling, a

bad smashup is inevitable. In its mid flight, between seven hundred and twelve

hundred yards, it "sleeps." If it hits anything while it is sleeping,

it drills a clean hole. From twelve hundred yards on, losing momentum and

equilibrium, it again wobbles, and this is no time to be struck by it.

In the hospital of San Sebastian I examine the

wound of a finely formed and muscular young man. Midway between knee and thigh

a wobbling bullet had ploughed a path two inches wide and three inches deep. It

was a clean path. Not an atom remained of the flesh that had filled that

groove. You how read this, just draw with a lead pencil a groove two inches

wide and three inches deep and you will more fully comprehend what happens to

human flesh when a high-powered, wobbling bullet goes tearing through it.

High-Velocity Bone Shatterers

THE

effect of such bullets on human bone can be readily imagined.

There is no reason, with modern antiseptic surgery, why a clean-drilled hold

thorough flesh and bone cannot be healed nicely. Unfortunately, such being the

terrific impact and wobble of our high-velocity bullets of to-day, the bone is

shattered for to great a distance into too many minute fragments. The only

thing to do is take off the limb.

When leaving the amputated in the wards of San

Sebastian, I chanced to wander into the hospital chapel. The Chapel of

Bethlehem it had been called once upon a time. It was very old, some two

centuries or so, and was a fine example of the architectural feats achieve by

the Spaniards in brick and stucco in a day when reinforce concrete was unheard

of. Wide arches of incredible flatness and supporting enormous weights were

revealed to be of brick by the spots where the plastering had come off. High

arches spanned deep-embrasured windows, in which some of the ancient, hand-hewn

sashes still remained. The high walls, rising to rafters far above, had caught

the dust of years on the uneven plaster, which gave a fathomless velvet depth

to the surface. The floor was of great, square marble flags.

Blasters of Flesh—and Repairers

THE

statues of Christ, the Virgin, and the Saints that had graced the

altar were long since gone. Gone, too, was the altar. Nothing remained save the

lofty alls and cool depth of shadow to suggest that it had been a chapel. And

as I stood in this place whence the worship of the gentle Nazarene had

departed, strong on my vision were the amputated limbs, gaping wounds, and

ruined bodies caused by our wobbling bullets.

Came another picture: I seemed to glimpse a

massed background of machinery and electrical apparatus, of weary-eyed

astronomers searching the heavens, and chemist and physicists dissecting the

atom, of teachers and preachers and great libraries of books. And against this

background, well to the fore, were two groups of men whose brows were the brows

of thinkers, and whose hands worked unceasingly at the making of devices. One

group toiled at the mixing of chemicals and the making of mechanisms for the

purpose of blasting human flesh and bone at longer distances and more

efficiently. The other group toiled likewise with chemicals and instruments,

seeking out new methods and greater knowledge of the constitution of man in

order that they might repair the blasted flesh and bone caused by the devices

of the first group.

Laughs for Our Descendants

SOME

day in the far future pictures will be pained like that, and our

descendants will gaze at them, shake their heads, and laugh at their silly

ancestors, just as we to-day gaze at pictures of witch burning, and shake our

heads and laugh at the silliness of our very immediate ancestors. Man has

climbed far. It would seem that his climb has only begun.

Out across the inner and outer harbors, in the

midst of a fleet of similar monsters, the grim monster, the Arkansas was

a striking sample of the mechanism produced by the war makers. Twelve million

dollars she cost. Her great guns, turned upon Vera Cruz for an hour or so,

could level the city to the ground as a stream of water would level a house of

sand. Magnificent universities have been founded on less than it cost to build

and equip her. The money expended on her would save from the White Plague a

hundred thousand times more lives than she will ever destroy.

The Arkansas and the Solace

OVER

a thousand skilled men are required to man her—skilled men such

as built the Panama Canal and whose skill might well be devoted to making the

Mississippi flood proof. Why, down in the bowels of the Arkansas,

imbedded in the thickest of armor plate, in the battle control station, an

enlisted sailor in the course of describing the new gyro-compass, gave me a

lecture that no college professor could have bettered and that no tyro in such

matters could have understood. Could Columbus or Captain Cook have stood beside

me, and tried to master the details of that intricate compass, I swear their

brains would have flown apart and they would have bitten their veins and

howled.

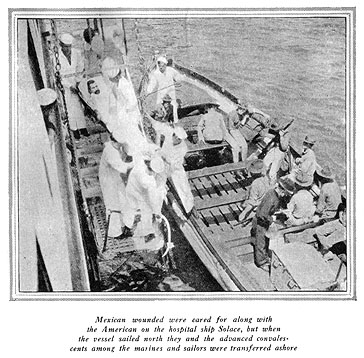

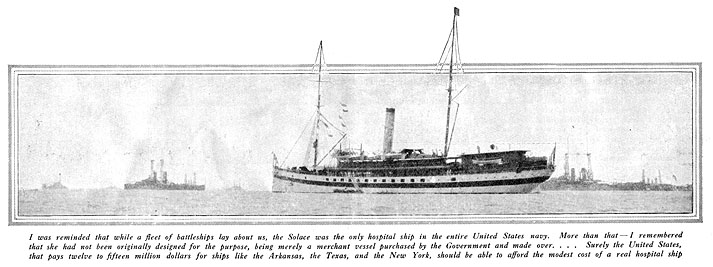

Quite in contrast, and lying not far away, was

the solitary hospital ship, the Solace. Spick-and-span, and sweet and

peaceful, and very antiseptic she was. I was followed up the gangway by two

young men who just brought off form shore. I walked up the incline on my good

two legs. They came up on their backs in wire-basket stretchers. A long roll of

body-blasted young men had preceded them in the previous two days. Seventeen of

these young men lay embalmed in caskets covered by the Stars and Stripes,

waiting transshipment to their homes in the States. Two more young men lay

dying. Threescore and more in various stages of recovery from body blasting lay

in the bright and airy 'tween-decks wards. A number of amputations had been

performed on them. The careful doctors, waiting, knew there were yet other

amputations to be performed to save the lives of some of the young men.

The Price of Service

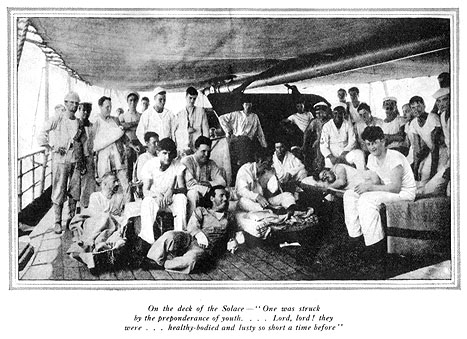

PASSING

through the wards, one was again struck by the preponderance

of youth. Lord, Lord! They were boys, healthy-bodied and lusty so short a time

before, now lying, lax-muscled, with drawn faces that told all the story of the

body blasting they had endured. One, alive and so lively just the other day,

now with one leg, searched my eyes as if for understanding and sympathy for the

terrible stump that screamed advertisement of the copper he had

received—smashed down, from the back of life, to be a cripple to the end of

his days. Another, a very boy, red-lipped and bright-eyed with fever, smiled

wistfully. There was little hope for him. He was conscious, and, perhaps as men

sometimes will be in such grievous circumstances, he was aware that time would

soon cease for him.

Oh, there was no whining among those lads! They

tell of one, shot in two places, who was fetched aboard crying bitterly and

indignantly. His plaint was that the Mexicans had got him unexpectedly before

he had had a chance to get even one of them. As he said, he wouldn't have

minded his own catastrophe if he had got one of them—only one of them.

The Dove Among the Eagles

THE

beautiful operating room was well appointed. There were

convalescent wards, segregated wards for infectious diseases, and, here and

there, offices and workrooms presided over by experts, such as ear and throat

specialists, eye specialists, stomach specialists. And there was a dentist and

a completely equipped dental parlor.

On deck, under the awnings, we drank long, cool

drinks and gazed across the creamy-crested, pea-green saves to the big looming

battleships, and on to the tiny, half-submerged atolls with lagoons of

chrysoprase, and to the low-stretching breakwater, the lighthouses slim and

white as votive candles, and the old fortresses of Santiago and San Juan de

Ulloa. Suddenly all the panorama narrowed to a sleek gray dove that perched on

the rail a dozen feet away, settled its wings, and preened its feathers.

Somehow, that little gray dove reminded me that,

while a fleet of battleships lay about us, the Solace was the only

hospital ship in the entire United States navy. More than that—I remembered

that she had not been originally designed for the purpose, being merely a

merchant vessel purchased by the Government and made over. Also, I remember

having traveled, years before, in tropic steamers, mere merchant vessels built

for money making, that were far better fitted for the tropics than was the

Solace.

Is the Nation So Poor?

SURELY

the United States, that pays twelve to fifteen million dollars

for ships like the Arkansas, the Texas, and the New York,

should be able to afford the modest cost of a real hospital ship, designed, not

for the making of dollars, but for the alleviation of the ills and injuries

that afflict its sailors and marines.

But there is justification for the existence of

that array of war monsters among which we lay. As long as individuals in a wild

country—say the head hunters and cannibals of the Solomon Islands—carry

killing weapons, even a philosopher, traveling among them, would be wise to go

armed. Neither algebraic nor high ethical arguments are efficacious

dissuadements to a kinky headed man-eater with an appetite. In those Solomon

Islands more than one scientist, for lack of a rifle had had his head decorate

the grass huts and his body served up succulently from the hot ovents.

Arms and Savagery

ON

a coral beach on the windward coast of Gudalcanar stands a

monument to the memory of the "Austrian Expedition." This was a party

of professors. They were equipped to pursue the vocations that obtain in a high

civilization. They carried sextants, barometers, thermometers, artificial

horizons, cameras, and fountain pens. They carried naturalists' shotguns of the

tiniest caliber, butterfly nets, geologists' hammers, and notebooks for all

sorts of records, also certain instruments with which to make skull

measurements of the natives they might meet. But what they did not carry was

Mauser rifles and long-barreled revolvers. They were not equipped for the

anthropophagi they encountered. One man came back from that expedition to tell

the tail, and he was merely a man in the employ of the professors. The column

stands on the beach to mark that once they had been. Their heads remain to this

day up in the bush of Guadalcanar.

As with individuals, so with nations. As long as

certain nations go armed in a wild and savage world, just so long must the

enlightened nations go armed. The wild and savage world, with its silly

man-killing devices, is doomed to pass. But until it passes, it would be

silliness on the part of the enlightened nations to put aside their

weapons.

An international police force and an

international police court will mark the beginning of the end of war. But as

yet these two institutions have not been founded. So the united States will be

compelled to go on building $15,000,000 battleships and training its young men

to the old red profession.

The point is: when wild and savage conditions

make it imperative for a man or nation to go armed, it is equally imperative

for the man or nation to go well armed. Ever has the sword, in the hands of the

strong breeds, made for wider areas and longer periods of peace. In the end it

is the sword that will make lasting and universal peace. When the last savage

nation is compelled to lay down its weapons, war will have ceased. War itself,

superior war if you please, will destroy itself.

And There We Are

BUT in the meantime—and there you are—what would have been the present situation if the United States had long since disarmed? Somehow, I, for one, cannot see the picture of Huerta listening to and accepting the high ethical advice of the United States.

From the June 6, 1914 issue of Collier's magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.