Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

"Pinched"

A Prison Experience

By Jack London

Illustrated by Hermann C. Wall

RODE into

Niagara Falls in a "side-door Pullman," or, in common parlance, a

boxcar. A flat car, by the way, is known among the fraternity as a

"gondola," with the second syllable emphasized and pronounced long.

But to return. I arrived in the afternoon and headed straight from the

freight-train to the falls. Once my eyes were filled with that wonderful vision

of downrushing water, I was lost. I could not tear myself away long enough to

"batter" the "privates" (domiciles) for my supper. Even a

set-down could not have lured me away. Night came on, a beautiful night of

moonlight, and I lingered by the falls until after eleven. Then it was up to me

to hunt for a place to "kip."

RODE into

Niagara Falls in a "side-door Pullman," or, in common parlance, a

boxcar. A flat car, by the way, is known among the fraternity as a

"gondola," with the second syllable emphasized and pronounced long.

But to return. I arrived in the afternoon and headed straight from the

freight-train to the falls. Once my eyes were filled with that wonderful vision

of downrushing water, I was lost. I could not tear myself away long enough to

"batter" the "privates" (domiciles) for my supper. Even a

set-down could not have lured me away. Night came on, a beautiful night of

moonlight, and I lingered by the falls until after eleven. Then it was up to me

to hunt for a place to "kip."

"Kip," "doss,"

"flop," "pound your ear," all mean the same thing, namely,

to sleep. Somehow I had a "hunch" that Niagara Falls was a

"bad" town for hoboes, and I headed out into the country. I climbed a

fence and "flopped" in a field. John Law would never find me there, I

flattered myself. I lay on my back in the grass and slept like a babe. It was

so balmy warm that I woke up not once all night. But with the first gray

daylight my eyes opened, and I remembered the wonderful falls. I climbed the

fence and started down the road to have another look at them. It was early—not

more than five o'clock—and not until eight o'clock could I begin to batter for

my breakfast. I could spend at least three hours by the river. Alas! I was

fated never to see the river nor the falls again.

The town was asleep when I entered it. As I came

along the quiet street, I saw three men coming towards me along the sidewalk.

They were walking abreast. Hoboes, I decided, who, like myself, had got up

early. In this surmise I was not quote correct. I was only sixty-six and

two-thirds per cent. correct. The men on each side were hoboes all right, but

the man in the middle wasn't. I directed my steps to the edge of the sidewalk

in order to let the trio go by. But it didn't go by. At some word from the man

in the center, all three halted, and he of the center addressed me.

I piped the lay on the instant. He was a

"fly-cop," and the two hoboes were his prisoners. John Law was up and

out after the early worm. I was a worm. Had I been richer by the experiences

that were to befall me in the next several months, I should have turned and run

like the very devil. He might have shot at me, but he'd have had to hit me to

get me. He'd never run after me, for two hoboes in the hand are worth more than

one on the get-away. But like a dummy I stood still when he halted me. Our

conversation was brief.

"What hotel are you stopping at?" he

queried.

He had me. I wasn't stopping at any hotel, and,

since I did not know the name of a hotel in the place, I could not claim

residence in any of them. Also, I was up too early in the morning. Everything

was against me.

"I just arrived," I said.

"Well, you just turn around and walk in

front of me, and not too far in front. There's somebody wants to see

you."

I was "pinched." I knew who wanted to

see me. With that "fly-cop" and the two hoboes at my heels, and under

the direction of the former, I led the way to the city jail. There we were

searched and our names registered. I have forgotten now under which name I was

registered. I gave the name of Jack Drake, but when they searched me they found

letters addressed to Jack London. This caused trouble and required explanation,

all of which has passed from my mind, and to this day I do not know whether I

was pinched as Jack Drake or Jack London. But one or the other, it should be

there to-day in the prison register of Niagara Falls. Reference can bring it to

light. The time was somewhere in the latter part of June, 1894. It was only a

few days after my arrest that the great railroad strike began.

From the office we were led to the

"Hobo" and locked in. The "Hobo" is that part of a prison

where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since

hoboes constitute the principal division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid

iron cage is called the "Hobo." Here we met several hoboes who had

been pinched already that morning, and every little while the door was unlocked

and two or three more were thrust in with us. At last, when we totaled sixteen,

we were lead upstairs into the court-room. And now I shall faithfully describe

what took place in that court-room, for know that my patriotic American

citizenship there received a shock from which it has never fully recovered.

In the court-room were the sixteen prisoners, the

judge, and two bailiffs. The judged seemed to act as his own clerk. There were

no witnesses. There were no citizens of Niagara Falls present to look on and

see how justice was administered in their community. The judge glanced at the

list of cases before him and called out a name. A hobo stood up. The judge

glanced at a bailiff. "Vagrancy, your honor," said the bailiff.

"Thirty days," said his honor. The hobo sat down, and the judge was

calling another name and another hobo was rising to his feet.

The trial of that hobo had taken just about

fifteen seconds. The trial of the next hobo came off with equal celerity. The

bailiff said, "Vagrancy, your honor," and his honor said,

"Thirty days." This it went like clockwork, fifteen seconds to a

hobo-and thirty days.

They are poor dumb cattle, I thought to myself.

But wait till my turn comes; I'll give his honor a "spiel." Part way

along in the performance his honor, moved by some whim, gave one of us an

opportunity to speak. As chance would have it, this man was not a genuine hobo.

He bore none of the earmarks of the professional "stiff." Had he

approached the rest of us, while waiting at a water-tank for a freight, we

should have unhesitatingly classified him as a gay-cat. "Gay-cat" is

the synonym for tenderfoot in Hoboland. This gay-cat was well along in

years-somewhere around forty-five, I should judge. His shoulders were humped a

trifle, and his face was seamed and weather-beaten.

For many years, according to his story, he had

driven team for some firm in (if I remember rightly) Lockport, New York. The

firm had ceased to prosper, and finally, in the hard times of 1893, had gone

out of business. He had been kept on to the last, though toward the last his

work had been very irregular. He went on and explained at length his

difficulties in getting work (when so many were out of work) during the

succeeding months. In the end, deciding that he would find better opportunities

for work on the lakes, he had started for Buffalo. Of course he was

"broke," and there he was. That was all.

"Thirty days," said his honor, and

called another hobo's name.

Said hobo got up. "Vagrancy, your

honor," said the bailiff, and his honor said, "Thirty days."

And so it went, fifteen seconds and thirty days

to each hobo. The machine of justice was grinding smoothly. Most likely,

considering how early it was in the morning, his honor had not yet had his

breakfast and was in a hurry.

But my American blood was up. Behind me there

were the many generations of my American ancestry. One of the kinds of liberty

those ancestors of mine had fought and died for was the right of trial by jury.

This was my heritage, stained sacred by their blood, and it devolved upon me to

stand up for it. All right, I threatened to myself; just wait till he gets to

me.

He got to me. My name, whatever it was, was

called, and I stood up. The bailiff said, "Vagrancy, your honor," and

I began to talk. But the judge began talking at the same time, and he said,

"Thirty days." I started to protest, but at that moment his honor was

calling the name of the next hobo on the list. His honor paused long enough to

say to me, "Shut up!" The bailiff forced me to sit down. And the next

moment that next hobo received thirty days, and the succeeding hobo was just in

the process of getting his.

When we had all been disposed of, thirty days to

each stiff, his honor, just as he was about to dismiss us, suddenly turned to

the teamster from Lockport, the one man he had allowed to talk.

"Why did you quit your job?" his honor

asked.

Now the teamster had already explained how his

job had quit him, and the question took him aback. "Your honor," he

began confusedly, "isn't that a funny question to ask?"

"Thirty days more for quitting your

job," said his honor, and the court was closed. That was the outcome. The

teamster got sixty days altogether, while the rest of us got thirty days.

We were taken down below, locked up, and given

breakfast. It was a pretty good breakfast, as prison breakfasts go, and it was

the best I was to get for a month to come.

As for me, I was dazed. Here was I, under

sentence, after a farce of a trial wherein I was denied not only my right of

trial by jury, but my right to plead guilty or not guilty. Another thing my

fathers had fought for flushed through my brain—habeas corpus. I'd show them.

But when I asked for a lawyer, I was laughed at. Habeas corpus was all right,

but of what good was it to me when I could communicate with no one outside the

jail? But I'd show them. They couldn't keep me in jail forever. Just wait till

I got out, that was all. I'd make them sit up. I knew something about the law

and my own rights, and I'd expose their maladministration of justice. Visions

of damage suits and sensational newspaper head-lines were dancing before my

eyes, when the jailers came in and began hustling us out into the main

office.

A policeman snapped a handcuff on my right wrist.

(Aha! thought I, a new indignity. Just wail till I get out.) On the left wrist

of a negro he snapped the other handcuff of that pair. He was a very tall

negro, well past six feet—so tall was he that when we stood side by side his

hand lifted mine up a trifle in the manacles. Also, he was the happiest and the

raggedest negro I have ever seen.

We were all handcuffed similarly, in pairs. This

accomplished, a bright, nickel-steel chain was brought forth, run down through

the links of all the handcuffs, and locked at front and rear of the double

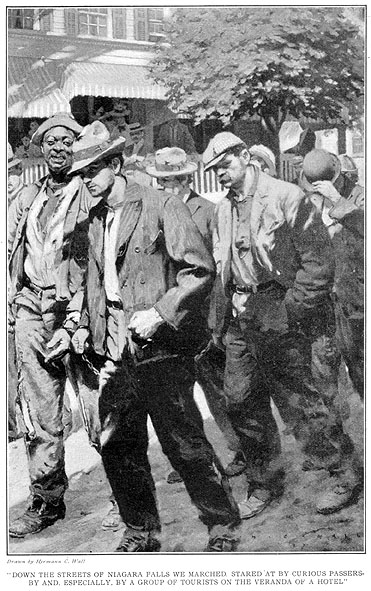

line. We were now a chain-gang. The command to march was given, and out we went

upon the street, guarded by two officers. The tall negro and I had the place of

honor. We led the procession.

After the tomb-like gloom of the jail, the

outside sunshine was dazzling. I had never known it to be so sweet as now when,

a prisoner with clanking chains, I knew that I was soon to see the last of it

for thirty days. Down through the streets of Niagara Falls we marched to the

railroad station, stared at by curious passers-by and, especially, by a group

of tourists on the veranda of a hotel that we marched passed.

There was plenty of slack in the chain, and with

much rattling and clanking we sat down, tow and town, in the seats of the

smoking car. Afire with indignation as I was at the outrage that had been

perpetrated on me and my forefathers, I was nevertheless too prosaically

practical to lose my head over it. This was all new to me. Thirty days of

mystery were before me, and I looked about me to find somebody who knew the

ropes. For I had already learned that I was not bound for a petty jail with a

hundred or so prisoners in it, but for a full-grown penitentiary with a couple

of thousand prisoners in it doing anywhere from ten days to ten years.

In the seat behind me, attached to the chain by

his wrist, was a squat, heavily built, powerfully muscled man. He was somewhere

between thirty-five and forty years of age. I sized him up. In the corners of

his eyes I saw humor and laughter and kindliness. As for the rest of him, he

was a brute beast, wholly unmoral, and with all the passion and turgid violence

of the brute beast. What saved him, what made him possible for me, were those

corners of his eyes—the humor and laughter and kindliness of the beast when

unaroused.

He was my "meat." I cottoned to him.

While my cuff-mate, the tall negro, mourned with chucklings and laughter over

some laundry he was sure to lose through his arrest, and while the train rolled

on toward Buffalo, I talked with the man in the seat behind me. He had an empty

pipe. I filled it for him with my precious cigarette tobacco—enough in a

single filling to make a dozen cigarettes. Nay, the more we talked the surer I

was that he was my meat, and I divided all my tobacco with him.

Now it happens that I am a fluid sort of

organism, with sufficient kinship with life to fit myself in 'most anywhere. I

laid myself out to fit in with that man, though little did I dream to what

extraordinary good purpose I was succeeding. He had never been in the

particular penitentiary to which we were going, but he had done

"one," "two," and "five spots" in various other

penitentiaries (a "spot" is a year), and he was filled with wisdom.

We became pretty chummy, and my heart bounded when he cautioned me to follow

his lead. He called me "Jack," and I called him "Jack."

The train stopped at a station about five miles

from Buffalo, and we, the chain-gang, got off. I do not remember the station,

but I am confident that it is some one of the following; Rocklyn, Rockwood,

Black Rock, Rockcastle, or Newcastle. But whatever the name of the place, we

were walked a short distance and then put on a street-car. It was an

old-fashioned car, with a seat, running the full length, on each side. All the

passengers who sat on one side were asked to move over to the other side, and

we, with a great clanking of chain, took their places. We sat facing them, I

remember, and I remember, too, the awed expression on the faces of the women,

who took us, undoubtedly, for convicted murderers and bank-robbers. I tried to

look my fiercest, but that cuff-mate of mine, the too happy negro, insisted on

rolling his eyes, laughing, and reiterating, "Oh, Lawdy! Lawdy!"

We left the car, walked some more, and were led

into the office of the Erie County penitentiary. Here we were to register, and

on that register one or the other of my names will be found. Also, we were

informed that we must leave in the office all our valuables, money, tobacco,

matches, pocket-knives, and so forth.

My new pal shook his head at me.

"If you do not leave your things here, they

will be confiscated inside," warned the official.

Still my pal shook his head. He was busy with his

hands, hiding his movements behind the other fellows. (Our handcuffs had been

removed.) I watched him and followed suit, wrapping up in a bundle in my

handkerchief all the things I wanted to take in. These bundles the two of us

thrust into our shirts. I noticed that our fellow-prisoners, with the exception

of one or two who had watches, did not turn over their belongings to the man in

the office. They were determined to smuggle them in somehow, trusting to luck;

but they were not so wise as my pal, for they did not wrap their things in

bundles.

Our erstwhile guardians gathered up the handcuffs

and chain and departed for Niagara Falls, while we, under new guardians, were

led away into the prison. While we were in the office our number had been added

to by other squads of newly arrived prisoners, so that we were not a procession

of forty or fifty strong.

Know, ye unimprisoned, that traffic is a

restricted inside a large prison as commerce was in the Middle Ages. Once

inside a penitentiary, one cannot move about at will. Every few steps are

encountered great steel doors or gates which are always kept locked. We were

bound for the barber-shop, but we encountered delays in the unlocking of doors

for us. We were thus delayed in the first hall we entered. A "hall"

is not a corridor. Imagine an oblong structure, build of bricks and rising six

stories high, each story a row of cells, say fifty cells in a row—in short,

imagine an oblong of colossal honey-comb. Place this on the ground and enclose

it in a building with a roof overhead and walls all around. Such an oblong and

encompassing building constitute a "hall" in the Erie County

penitentiary. Also, to complete the picture, see a narrow gallery, with a steel

railing, running the full length of each tier of cells, and at the ends of the

oblong see all these galleries, from both sides, connected by a fire-escape

system of narrow steel stairways.

We were halted in the first hall, waiting for

some guard to unlock a door. Here and there, moving about, were convicts, with

close-cropped heads and shaven faces, and garbed in prison stripes. One such

convict I noticed above us on the gallery of the third tier of cells. He was

standing on the gallery and leaning forward, his arms resting on the railing,

apparently oblivious of our presence. He seemed staring into vacancy. My pal

made a slight hissing noise. The convict glanced down. Motioned signals passed

between them. Then through the air soared the handkerchief bundle of my pal.

The convict caught it, and like a flash it was out of sight in his shirt. and

he was staring into vacancy. My pal had told me to follow his lead. I watched

my chance when the guard's back was turned, and my bundle followed the other

one into the shirt of the convict.

A minute later the door was unlocked, and we

filed into the barber-shop. Here were more men in convict stripes. They were

prison barbers. Also, there were bath-tubs, hot water, soap, and

scrubbing-brushes. We were ordered to strip and bathe, each man to scrub his

neighbors back—a needless precaution, this compulsory bath, for the prison

swarmed with vermin. After the bath, we were each given a prison

clothes-bag.

"Put all your clothes in the bags,"

said the guard. "It's no good trying to smuggle anything in. You've got to

line up naked for inspection. Men for thirty days or less keep their shoes and

suspenders. Men for more than thirty days keep nothing."

This announcement was received with

consternation. How could naked men smuggle anything past an inspection? Only my

pal and I were safe. But it was right here that the convict barbers got in

their work. They passed among the poor newcomers, kindly volunteering to take

charge of their precious little belongings, and promised to return them later

in the day. Those barbers were philanthropists—to hear them talk. As in the

case of Fra Lippo Lippi, there was prompt disemburdening. Matches, tobacco,

rice-paper, pipes, knives, money, everything, flowed into the capacious shirts

of the barbers. They fairly bulged with the spoil, and the guards made believe

not to see. To cut the story short, nothing was ever returned. The barbers

never had any intention of returning what they had taken. They considered it

legitimately theirs. It was the barber-shop graft. There were many grafts in

that prison, as I was to learn, and I, too, was destined to become a

grafter—thanks to my new pal.

There were several chairs, and the barbers worked

rapidly. The quickest shaves and hair-cuts I have ever seen were given in that

shop. The men lathered themselves, and the barbers shaved them at the rate of a

man a minute. A hair-cut took a trifle longer. In three minutes the down of

eighteen was scraped from my face and my head was a smooth as a billiard-ball

just sprouting a crop of bristles. Beards, mustaches, like our clothes and

everything, came off. Take my word for it, we were a villainous-looking gang

when they got through with us. I had not realized before how really altogether

bad we were.

Then came the line-up, forty or fifty of us,

naked as Kipling's heroes who stormed Lungtungpen. To search us was easy. There

were only our shoes and ourselves. Two or three rash spirits, who had doubted

the barbers, had the goods found on them—which goods, namely, tobacco, pipes,

matches, and small change, were quickly confiscated. This over, our new clothes

were brought to us—stout prison shirts, and coats and trousers conspicuously

striped. I had always lingered under the impression that the convict stripes

were put on a man only after he had been convicted of a felony. I lingered no

longer, but put on the insignia of shame and got my first taste of marching the

lock-step.

In single file, close together, each man's hands

on the shoulders of the man in front, we marched on into another large hall.

Here we were ranged up against the wall in a long line and ordered to strip our

left arms. A youth, a medical student who was getting in his practice on cattle

such as we, came down the line. He vaccinated just about four times as rapidly

as the barbers shaved. With a final caution to avoid rubbing our arms against

anything, we were led away to our cells.

In my cell was another man who was to be my

cell-mate. He was a young, manly fellow, not talkative, but very capable,

indeed as splendid a fellow as one could meet with in a day's ride, and this in

spite of the fact that he had just recently finished a two-year term in some

Ohio penitentiary.

Hardly had we been in our cell half an hour when

a convict sauntered down the gallery and looked in. It was my pal. He had the

freedom of the hall, he explained. He was to be unlocked at six in the morning

and not locked up again till nine at night. He was in with the "push"

in that hall, and had been promptly appointed a trusty of the kind technically

known as "hall-man." The man who had appointed him was also a

prisoner and a trusty, and was known as "first hall-man." There were

thirteen hall-men in that hall. Ten of them had charge each of a gallery of

cells, and over them were the first, second, and third hall-men.

We newcomers were to stay in our cells for the

rest of the day, my pal informed me, so that the vaccine would have a chance to

take. Then next morning we would be put to hard labor in the prison-yard.

"But I'll get you out of the work as soon as

I can," he promised. "I'll get one of the hall-men fired and have you

put in his place."

He put his hand into his shirt, drew out the

handkerchief containing my precious belongings, passed it in to me through the

bars, and went on down the gallery.

I opened the bundle. Everything was there. Not

even a match was missing. I shared the makings of a cigarette with my

cell-mate. When I started to strike a match for a light, he stopped me. A

flimsy, dirty comforter lay in each of our bunks for bedding. He tore off a

narrow strip of the thin cloth and rolled it tightly and telescopically into a

long and slender cylinder. This he lighted with a precious match. The cylinder

of tight-rolled cotton cloth did not flame. On the end a coal of fire slowly

smoldered. It would last for hours, and my cell-mate called it a

"punk." When it burned short, all that was necessary was to make a

new punk, put the end of it against the old, blow on them, and so transfer the

glowing coal. Why, we could have given Prometheus pointers on the conserving of

fire.

At twelve o'clock dinner was served. At the

bottom of our cage-door was a small opening like the entrance of a runway in a

chicken-yard. Through this were thrust two hunks of dry bread and two pannikins

of "soup." A portion of soup consisted of about a quart of hot water

with a lonely drop of grease floating on its surface. Also, there was some salt

in the water.

We drank the soup, but we did not eat the bread.

Not that we were not hungry, and not that the bread was uneatable. It was

fairly good bread. But we had reasons. My cell-mate had discovered that our

cell was alive with bedbugs. In all the cracks and interstices between the

bricks where the mortar had fallen out great colonies flourished. The natives

even ventured out in the broad daylight and swarmed over the walls and ceilings

by hundreds. My cell-mate was wise in the ways of the beasts. Like Childe

Roland, dauntless the slug-horn to his lips he bore. Never was there such as

battle. It lasted for hours. It was a shambles. And when the last survivors

fled to their brick-and-mortar fastnesses, our work was only half done. We

chewed mouthfuls of our bread until it was reduced to the consistency of putty,

and when a fleeing belligerent escaped into a crevice between the bricks, we

promptly walled him in with a daub of the chewed bread. We toiled on until the

light grew dim and until every hold, nook, and cranny was closed. I shudder to

think of the tragedies of starvation and cannibalism that must have ensued

behind those bread-plastered ramparts.

We threw ourselves on our bunks, tired out and

hungry, to wait for supper. It was a good day's work well done. In the weeks to

come we at least should not suffer from the hosts of vermin. We had foregone

our dinner, saved our hides at the expense of our stomachs; but we were

content. Alas for the futility of human effort! Scarcely was our long task

completed when a guard unlocked our door. A redistribution of prisoners was

being made, and we were taken to another cell and locked in two galleries

higher up.

Early next morning our cells were unlocked, and

down in the hall the several hundred prisoners of us formed the lock-step and

marched out into the prison-yard to go to work. The Erie Canal runs right by

the back yard of the Erie County penitentiary. Our task was to unload

canal-boats, carrying huge stay-bolts on our shoulders, like railroad ties,

into the prison. As I worked I sized up the situation and studied the chances

for a get-away. There wasn't the ghost of a show. Along the tops of the walls

marched guards armed with repeating rifles, and I was told, furthermore, that

there were machine-guns in the sentry-towers.

I did not worry. Thirty days were not so long.

I'd stay those thirty days, and add to the store of material I intended to use,

when I got out, against the harpies of justice. I'd show what an American boy

could do when his rights and privileges had been trampled on the way mine had.

I had been denied my right of trial by jury. I had been denied my right to

plead guilty or not guilty; I had been denied a trial even (for I couldn't

consider that what I had received at Niagara Falls was a trial); I had not been

allowed to communicate with a lawyer or anyone, and hence had been denied my

right for suing for a writ of habeas corpus; my face had been shaved, my hair

cropped close, convict stripes has been put upon my body; I was forced to toil

hard on a diet of bread and water and to march the shameful lock-step with

armed guards over me—and all for what? What had I done? What crime had I

committed against the good citizens of Niagara Falls that all this vengeance

should be wreaked upon me? I had not even violated their

"sleeping-out" ordinance. I had slept in the country, outside their

jurisdiction, that night. I had not even begged for a meal, or battered for a

"light-piece" on the streets. All that I had done was to walk along

their sidewalk and gaze at their picayune waterfall. And what crime was there

in that? Technically I was guilty of no misdemeanor. All right, I'd show them

when I got out.

The next day I talked with a guard. I wanted to

send for a lawyer. The guard laughed at me. So did the other guards. I really

was incommunicado so far as the outside world was concerned. I tried to

write a letter out, but I learned that all letters were read and censored or

confiscated by the prison authorities, and that "short-timers" were

not allowed to write letters, anyway. A little later I tried smuggling letters

out by men who were released, but I learned that they were searched and the

letters found and destroyed. Never mind. It all helped to make it a blacker

case when I did get out.

But as the prison days went by (which I shall

describe in the next chapter), I "learned a few." I heard tales of

the police, and police courts, and lawyers, that were unbelievable and

monstrous. Men, prisoners, told me of personal experiences with the police of

great cities that were awful. And more awful were the hearsay tales they told

me concerning men who had died at the hands of the police and therefore could

not testify for themselves. Years afterward, in the report of the Lexow

Committee, I was to read tales true and more awful than those told to me. But

in the meantime, during the first days of my imprisonment, I scoffed at what I

heard.

As the days went by, however, I began to be

convinced. I saw with my own eyes, there in that prison, things unbelievable

and monstrous. And the more convinced I became, the profounder grew the respect

in me for the sleuth-hounds of the law and for the whole institution of

criminal justice. My indignation ebbed away, and into my being rushed the tides

of fear. I saw at last, clear-eyed, what I was up against. I grew meek and

lowly. Each day I resolved more emphatically to make no rumpus when I got out.

All I asked, when I got out, was a chance to fade away from the landscape. And

that was just what I did to when I was released. I kept my tongue between my

teeth, walked softly, and sneaked for Pennsylvania, a wiser and humbler man.

From the July 1907 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.