Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

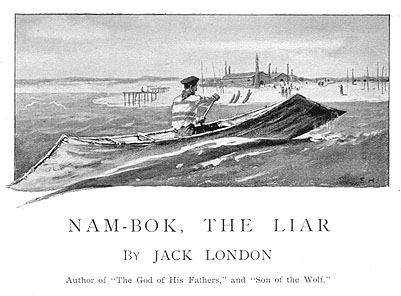

![]() BIDARKA,* [* Skin boat of the Esquimo.] is it not so? Look! A

bidarka, and one man who drives clumsily with a paddle!"

BIDARKA,* [* Skin boat of the Esquimo.] is it not so? Look! A

bidarka, and one man who drives clumsily with a paddle!"

Old Bask-Wah-Wan was rose to her knees, trembling

with weakness and eagerness, and gazed out over the sea.

"Nam-Bok was ever clumsy at the

paddle," she maundered, reminiscently, shading the sun from her eyes and

staring across the silver-spilled water. "Nam-Bok was ever clumsy. I

remember——"

But the women and children laughed loudly, and

there was a gentle mockery in their laughter, and her voice dwindled till her

lips moved without sound.

Koogah lifted his grizzled head from his

bone-carving and followed the path of her eyes. Except when wild yaws took it

off its course, a bidarka was heading in for the beach. Its occupant was

paddling with more strength than dexterity, and made his approach along the

zig-zag line of most resistance. Koogah's head dropped to his work again, and

on the ivory tusk between his knees he scratched the dorsal fin of a fish the

like of which never swam in the sea.

"It is doubtless the man from the next

village," he said, finally, "come to consult with me about the making

of things on bone. And the man is a clumsy man. He will never know

how."

"It is Nam-Bok," old Bask-Wah-Wan

repeated. "Should I not know my son?" she demanded, shrilly. "I

say, and I say again, it is Nam-Bok."

"And so thou hast said these many

summers," one of the women chided, softly. "Ever when the ice passed

out of the sea hast thou sat and watched through the long day, saying at each

chance canoe, 'This is Nam-Bok.' Nam-Bok is dead, O Bask-Wah-Wan, and the dead

do not come back."

" Nam-Bok!" the old woman cried, so

loud and clear that the whole village was startled and looked at her.

She struggled to her feet and tottered down the

sand. She stumbled over a baby lying in the sun, and the mother hushed its

crying and hurled harsh words after the old woman, who took no notice. The

children ran down the beach in advance of her, and as the man in the bidarka

drew closer, nearly capsizing with one of his ill-directed strokes, the women

followed. Koogah dropped his walrus tusk and went also, leaning heavily on his

staff, and after him loitered the men in twos and threes.

The bidarka turned broadside and the ripple of

surf threatened to swamp it, only a naked boy ran into the water and pulled the

bow high up on the sand. The man stood up and sent a questioning glance along

the line of villagers. A rainbow sweater, dirty and the worse for wear, clung

loosely to his broad shoulders, and a red cotton handkerchief was knotted in

sailor fashion about his throat. A fisherman's tam-o'-shanter on his

close-clipped head, and dungaree trousers and heavy brogans, completed his

outfit.

But he was, none the less, a striking personage

to these simple fisher-folk of the great Yukon Delta, who all their lives had

stared out on Bering Sea, and in that time had seen but two white men, the

census enumerator and a lost Jesuit priest. They were a poor people, with

neither gold in the ground nor valuable furs in hand, so the whites had passed

them afar. Also, the Yukon, through the thousands of years, had shoaled that

portion of the sea with the detritus of Alaska till vessels grounded out of

sight of land. So the sodden coast, with its long inside reaches and huge

mud-land archipelagoes, was avoided by the ships of men, and the fisher-folk

knew not that such things were.

Koogaa the Bone-Scratcher, retreated backward in

sudden haste, tripping over his staff and falling to the ground. "

Nam-Bok!" he cried, as he scrambled wildly for footing. " Nam-Bok,

who was blown off to sea, come back!"

The men and women shrank away, and the children

scuttled off between their legs. Only Opee-Kwan was brave, as befitted the head

man of the village. He strode forward and gazed long and earnestly at the

newcomer.

"It is Nam-Bok," he said, at last, and

at the conviction of his voice the women wailed apprehensively and drew farther

away.

The lips of the stranger moved indecisively, and

his brown throat writhed and wrestled with unspoken words.

"La, la, it is Nam-Bok," Bask-Wah-Wan

croaked, peering up into his face. "Ever did I say Nam-Bok would come

back."

"Ah, it is Nam-Bok come back." This

time it was Nam-Bok himself who spoke, putting a leg over the side of the

bidarka and standing with one foot afloat and one ashore. Again his throat

writhed and wrestled as he grapple after forgotten words. And when the words

came forth they were strange of sound, and a spluttering of the lips

accompanied the gutturals.

"Greeting, O brothers," he said,

"brothers of old time before I went away with the off-shore

wind."

He stepped out with both feet on the sand, and

Opee-Kwan waved him back.

"Thou art dead, Nam-Bok," he said.

Nam-Bok laughed. "I am fat."

"Dead men are not fat," Opee-Kwan

confessed. "Thou has fared well, but it is strange. No man may mate with

the off-shore wind and come back on the heels of the years."

"I have come back," Nam-Bok answered,

simply.

"Mayhap thou art a shadow, then, a passing

shadow of the Nam-Bok that was. Shadows come back."

"I am hungry. Shadows do not eat."

But Opee-Kwan doubted, and brushed his hand

across his brow in sore puzzlement. Nam-Bok was likewise puzzled, and as he

looked up and down the line found no welcome in the eyes of the fisher-folk.

The men and women whispered together. The children stole timidly back among

their elders, and bristling dogs fawned up to him and sniffed suspiciously.

"I bore thee, Nam-Bok, and I gave thee suck

when thou wast little," Bask-Wah-Wan whimpered, drawing closer; "and

shadow though thou be, or no shadow, I will give thee to eat now."

Nam-Bok made to come to her, but a growl of fear

and menace warned him back. He said something in a strange tongue which sounded

like "Goddam," and added, "No shadow am I, but a man."

"Who may know concerning the things of

mystery?" Opee-Kwan demanded, half of himself and half of his

tribespeople. "We are, and in breath we are not. If the man may become

shadow, may not the shadow become man? Nam-Bok was, but is not. This we know,

but we do not know if this be Nam-Bok or the shadow of Nam-Bok."

Nam-Bok cleared his throat and made answer.

"In the old time long ago, thy father's father, Opee-Kwan, went away and

came back on the heels of the years. Nor was a place by the fire denied him. It

is said"—he paused significantly, and they hung on his

utterance—"it is said," he repeated, driving his point home

with deliveration, "that Sipsip, his klooch,* [*

Woman.] bore him two sons after he came back."

"But he had no doings with the off-shore

wind," Opee-Kwan retorted. "He went away into the heart of the land,

and it is in the nature of things that a man may go on and on into the

land."

"And likewise the sea. But that is neither

here nor there. It is said . . . that thy father's father told strange tales of

the things he saw."

"Ay, strange tales he told."

"I, too, have strange tales to tell,"

Nam-Bok stated, insidiously. And, as they wavered, "and presents,

likewise."

He pulled from the bidarka a shawl, marvelous of

texture and color, and flung it about his mother's shoulders. The women voiced

a collective sigh of admiration, and old Bask-Wah-Wan ruffled the gay material

and patted it and crooned in childish joy.

"He has tales to tell," Koogah

muttered. "And presents," a woman seconded.

And Opee-Kwan knew that his people were eager,

and further, he was aware himself of an itching curiosity concerning those

untold tales. "The fishing has been good," he said, judiciously,

"and we have oil in plenty. So come, Nam-Bok; let us feast."

Two of the men hoisted the bidarka on their

shoulders and carried it up to the fire. Nam-Bok walked by the side of

Opee-Kwan, and the villagers followed after, save those of the women who

lingered a moment to lay caressing fingers on the shawl.

There was little talk while the feast went on,

though many and curious were the glances stolen at the son of Bask-Wah-Wan.

This embarrassed him—not because he was modest of spirit, however, but

for the fact that the stench of the seal-oil had robbed him of his appetite,

and that he keenly desired to conceal his feelings on the subject.

"Eat; thou art hungry," Opee-Kwan

commanded, and Nam-Bok shut both his eyes and shoved his fist into the big pot

of putrid fish.

"La, la, be not ashamed. The seal were many

this year, and strong men are ever hungry." And Bask-Wah-Wan sopped a

particularly offensive chunk of salmon into the oil and passed it fondly and

dripping to her son.

In despair, when premonitory symptoms warned him

that his stomach was not so strong as of old, he filled his pipe and struck up

a smoke. The people fed on noisily and watched. Few of them could boast of

intimate acquaintance with the precious weed, though now and again small

quantities and abominable qualities were obtained in trade from the Esquimos to

the northward. Koogah, sitting next to him, indicated that he was not averse to

taking a draw, and between two mouthfuls, with the oil thick on his lips,

sucked away at the amber stem. And thereupon Nam-Bok held his stomach with a

shaky hand and declined the proffered return. Koogah could keep the pipe, he

said, for he had intended so to honor him from the first. And the people licked

their fingers and approved of his liberality.

Opee-Kwan rose to his feet. "And now, O

Nam-Bok, the feast is ended, and we would listen concerning the strange things

you have seen."

The fisher-folk applauded with their hands, and

gathered about them their work, prepared to listen. The men were busy

fashioning spears and carving on ivory, while the women scraped the fat from

the hides of the hair seal and made them pliable or sewed muclucs with threads

of sinew. Nam-Bok's eyes roved over the scene, but there was not the charm

about it that his recollection had warranted him to expect. During the years of

his wandering he had looked forward to just this scene, and now that it had

come he was disappointed. It was a bare and meager life, he deemed, and not to

be compared to the one he had become used to. Still, he would open their eyes a

bit, and his own eyes sparkled at the thought.

"Brothers," he began, with the smug

complacency of a man about to relate the big things he has done, "it was

late summer of many summers back, with much such weather as this promises to

be, when I went away. You all remember the day, when the gulls flew low, and

the wind blew strong from the land, and I could not hold my bidarka against it.

I tied the covering of the bidarka about me, so that no water could get in, and

all of the night I fought with the storm. And in the morning there was no land,

only the sea, and the off-shore wind held me close in its arms and bore me

along. Three such nights whitened into dawn and showed me no land, and the

off-shore wind would not let me go.

"And when the fourth day came I was as a

madman. I could not dip my paddle for want of food, and my head went round and

round, what of the thirst that was upon me. But the sea was no longer angry,

and the soft south wind was blowing, and as I looked about me I saw a sight

that made me think I was indeed mad."

Nam-Bok paused to pick a silver of salmon lodged

between his teeth, and the men and women, with idle hands and heads craned

forward, waited.

"It was a canoe, a big canoe. If all the

canoes I have ever seen were made into one canoe, it would not be so

large."

There were exclamations of doubt, and Koogah,

whose years were many, shook his head.

"If each bidarka were as a grain of

sand," Nam-Bok defiantly continued, "and if there were as many

bidarkas as there be grains of sand in this beach, still they would not make so

big a canoe as this I saw on the morning of the fourth day. It was a very big

canoe, and it was called a schooner. I saw this thing of wonder, this

great schooner, coming after me, and on it I saw men——"

"Hold, O Nam-Bok!" Opee-Kwan broke in.

"What manner of men were they—big men?"

"Nay, mere men like you and me."

"Did the big canoe come fast?"

"Ay."

"The sides were tall, the men

short."

Opee-Kwan stated the premises with conviction.

"And did these men dip with long paddles?"

Nam-Bok grinned. "There were no

paddles," he said.

Mouths remained opened, and a long silence

ensued. Opee-Kwan reached for Koogah's pipe for a couple of contemplative

sucks. One of the younger women giggled nervously, and drew upon herself angry

eyes.

"There were no paddles?" Opee-Kwan

asked, softly, returning the pipe.

"The south wind was behind," Nam-Bok

explained.

"But the wind-drift is slow."

"The schooner had wings—thus." He

sketched a diagram of masts and sails in the sand, and the men crowded around

and studied it. The wind was blowing briskly, and, and for more graphic

elucidation he seized the corners of his mother's shawl and spread them out

till it bellied like a sail. Bask-Wah-Wan scolded and struggled, but was blown

down the beach for a score of feet and left breathless and stranded in a heap

of driftwood. The men uttered sage grunts of comprehension, but Koogah suddenly

tossed back his hoary head.

"Ho! ho!" he laughed. "A foolish

thing, this big canoe! A most foolish thing! The plaything of the wind!

Wheresoever the wind goes, it goes, too, No man who journeys therein may name

the landing beach, for always he goes with the wind, and the wind goes

everywhere, but no man knows where."

"It is so," Opee-Kwan supplemented,

gravely. "With the wind, the going is easy, but against the wind a man

striveth hard, and for that they had no paddles these men on the big canoe did

not strive at all."

"Small need to strive," Nam-Bok cried,

angrily. "The schooner went likewise against the wind."

"And what said you made the sch-sch-schooner

go?", Koogah asked, tripping craftily over the strange word.

"The wind," was the impatient

response.

"Then the wind made the sch-sch-schooner go

against the wind." Old Koogah dropped an open leer to Opee-Kwan, and, the

laughter growing around him, continued: "The wind blows from the south and

blows the schooner south. The wind blows against the wind. The wind blows one

way and the other at the same time. It is very simple. We understand, Nam-Bok.

We clearly understand."

"Thou art a fool!"

"Truth falls from my lips," Koogah

answered, meekly. "I was over-long in understanding, and the thing was

simple."

But Nam-Bok's face was dark, and he said rapid

words which they had never heard before. Bone-scratching and skin-scraping were

resumed, but he shut his lips tightly on the tongue that could not be

believed.

"This sch-sch-schooner," Koogah

imperturbably asked, "it was made of a big tree?"

"It was made of many trees," Nam-Bok

snapped, shortly. "It was very big."

He lapsed into sullen silence again, and

Opee-Kwan nudged Koogah, who shook his head with slow amazement and murmured,

"It is very strange."

Nam-Bok took the bait. "That is

nothing," he said, airily, "you should see the steamer. As the

grain of sand is to the bidarka, as the bidarka is to the schooner, so the

schooner is to the steamer. Further, the steamer is made of iron. It is all

iron."

"Nay, nay, Nam-Bok," cried the head

man; "how can that be? Always iron goes to the bottom. For behold, I

received an iron knife in trade from the head man of the next village, and

yesterday the iron knife slipped from my fingers and went down, down, into the

sea. To all things there be law. Never was there one thing outside the law.

This we know. And, moreover, we know that things of a kind have the one law,

and that all iron has the one law. So unsay thy words, Nam-Bok, that we may yet

honor thee."

"It is so," Nam-Bok persisted.

"The steamer is all iron and does not sink."

"Nay, nay; this cannot be."

"With my own eyes I saw it."

"It is not in the nature of

things."

"But tell me, Nam-Bok," Koogah

interrupted, for fear the tale would go no further; "tell me the manner of

these men in finding their way across the sea when there is no land by which to

steer."

"The sun points out the path."

"But how?"

"At midday the head of the schooner takes a

thing through which his eye looks at the sun, and then he makes the sun climb

down out of the sky to the edge of the earth."

"Now, this be evil medicine!" cried

Opee-Kwan, aghast at the sacrilege. The men held up their hands in horror and

the women moaned. "This be evil medicine. It is not good to misdirect the

great sun which drives away the night and gives us the seal, the salmon and

warm weather."

"What if it be evil medicine?" Nam-Bok

demanded, truculently. "I, too, have looked through the thing at the sun

and made the sun climb down out of the sky."

Those who were nearest drew away from him

hurriedly, and a woman covered the face of a child at her breast so that his

eye might not fall upon it.

"But on the morning of the fourth day, O

Nam-Bok," Koogah suggested; "on the morning of the fourth day when

the sch-sch-schooner came after thee?"

"I had little strength left in me and could

not run away. So I was taken on board, and water was poured down my throat and

good food was given me. Twice, my brothers, you have seen a white man. These

men were white and as many as have I fingers and toes. And when I saw they were

full of kindness, I took heart, and I resolved to bring away with me report of

all that I saw. And they taught me the work they did, and gave me good food and

a place to sleep.

"And day after day we went over the sea, and

each day the head man drew the sun down out of the sky and made it tell where

we were. And when the waves were kind we hunted the fur seal, and I marveled

much, for always did they fling the meat and the fat away and save only the

skin."

Opee-Kwan's mouth was twitching violently, and he

was about to make denunciation of such waste when Koogah kicked him to be

still.

"After a weary time, when the summer was

gone, and the bite of the frost come into the air, the head man pointed the

nose of the schooner south. South and east we traveled for days upon days, with

never the land in sight, and we were near to the village from which hailed the

men——"

"How did they know they were near?"

Opee-Kwan, unable to contain himself longer, demanded. "There was no land

to see." Nam-Bok glowered on him wrathfully. "Did I not say the head

man brought the sun down out of the sky?"

Koogah interposed, and Nam-Bok went on.

"As I say, when we were near that village a

great storm blew up, and in the night we were helpless, and knew not where we

were——"

"Thou has just said the head man

knew——"

"O peace, Opee-Kwan! Thou are a fool and

cannot understand. As I say, when we were helpless in the night, when I heard,

above the roar of the storm, the sound of the sea on the beach. And next we

struck with a mighty crash and I was in the water swimming. It was a rock-bound

coast, with one patch of beach in many miles, and the law was that I should dig

my hands into the sand and draw myself clear of the surf. The other men must

have pounded against the rocks, for none of them came ashore but the head man,

and him I knew only by the ring on his finger.

"When day came, there being nothing of the

schooner, I turned my face to the land and journeyed into it that I might get

food and look upon the faces of people. And when I came to a house I was taken

in and given to eat, for I had learned their speech, and the white men are ever

kindly. And it was a house bigger than all the houses built by us and our

fathers before us."

"It was a mighty house," Koogah said,

masking his unbelief with wonder.

"And many trees went into the making of such

a house," Opee-Kwan added, taking the cue.

"That is nothing." Nam-Bok shrugged his

shoulders in belittling fashion.

"As our houses are to that house, so that

house was to the houses I was yet to see."

"And they are not big men?" Opee-Kwan

queried.

"Nay; mere men like you and me,"

Nam-Bok answered. "I had cut a stick that I might walk in comfort, and

remembering that I was to bring report to you, my brothers, I cut a notch in

that stick for each person who lived in that house. And I stayed there many

days, and worked, for which they gave me money, a thing of which you know

nothing, but which is very good.

"And one day I departed from that place to

go farther into the land. And as I walked I met many people, and I cut smaller

notches in the stick that there might be room for all. Then I came upon a

strange thing. On the ground before me was a bar of iron, as big in thickness

as my arm, and a long step away was another bar of iron——"

"Then wert thou a rich man," Opee-Kwan

asserted; "for iron be worth more than anything else in the world. It

would have made many knives."

"Nay, it was not mine."

"It was a find, and a find be

lawful."

"Not so; the white had placed it there. And,

further, these bars were so long that no man could carry them away—so

long that as far as I could see, there was no end to them."

"Nam-Bok, that is very much iron,"

Opee-Kwan cautioned.

"Ay, it was hard to believe with my own eyes

upon it; but I could not gainsay my eyes. And as I looked I

heard——" He turned abruptly upon the head man.

"Opee-Kwan, thou hast heard the sealion bellow in his anger. Make it plain

in thy mind of as many sealions as there be waves to the sea, and make it plain

that all these sealions be made into one sealion, and as that one sealion would

bellow so bellowed the thing I heard."

The fisher-folk cried aloud in astonishment, and

Opee-Kwan's jaw lowered and remained lowered.

"And in the distance I saw a monster like

unto a thousand whales. It was one-eyed, and vomited smoke, and it snorted with

exceeding loudness. I was afraid and ran with shaking legs along the path

between the bars. But it came with the speed of the wind, this monster, and I

leaped the iron bars, with its breath hot on my face——"

Opee-Kwan gained control of his jaw again.

"And—and then, O Nam-Bok?"

"Then it came by on the bars, and harmed me

not, and when my legs could hold me up again it was gone from sight. And it is

a very common thing in that country. Even the women and children are not

afraid. Men make them to do work, these monsters."

"As we make our dogs do work?" Koogah

asked, with skeptic twinkle in his eye.

"Ay, as we make our dogs do work."

"And how do they breed, these—these

things?" Opee-Kwan questioned.

"They breed not at all. Men fashion them

cunningly of iron, and feed them with stone, and give them water to drink. The

stone becomes fire, and the water becomes steam, and the steam of the water is

the breath of their nostrils, and——"

"There, there, O Nam_Bok," Opee-Kwan

interrupted. "Tell us of other wonders. We grow tired of this which we may

not understand."

"You do not understand?" Nam-Bok asked,

despairingly.

"Nay, we do not understand," the men

and women wailed back. "We cannot understand."

Nam-Bok thought of a combined harvester, and of

the machines wherein visions of living men were to be seen, and of the machines

from which came the voices of men, and he knew his people could never

understand.

"Dare I say I rode this iron monster through

the land?" he asked, bitterly.

Opee-kwan threw up his hands, palms outward, in

open incredulity. "Say on; say anything. We listen."

"Then did I ride the iron monster, for which

I gave money——"

"Thou saidst it was fed with

stone."

"And likewise, thou fool, I said money was a

thing of which you know nothing. As I say, I rode the monster through the land,

and through many villages, until I came to a big village on a salt arm of the

sea. And the houses shoved their roofs among the stars in the sky, and the

clouds drifted by them, and everywhere was much smoke. And the roar of that

village was like the roar of the sea in storm, and the people were so many that

I flung away my stick and no longer remembered the notches upon it."

"Hadst thou made small notches," Koogah

reproved, "thou mightst have brought report."

Nam-Bok whirled upon him in anger. "Had I

made small notches! Listen, Koogah, thou scratcher of bone! If I had made small

notches, neither the stick, nor twenty sticks, could have bore them—nay,

not all the driftwood of all the beaches between this village and the next. And

if all of you, the women and children as well, were twenty times as many, and

if you had twenty hands each, and in each hand a stick and a knife, still the

notches could not be cut for the people I saw, so many were they and so fast

did they come and go."

"There cannot be so many people in all the

world," Opee-Kwan objected, for he was stunned and his mind could not

grasp such magnitude of numbers.

"What dost thou know of all the world and

how large it is?" Nam-Bok demanded.

"But there cannot be so many people in one

place."

"Who are thou to say what can be and what

cannot be?"

"It stands to reason there cannot be so many

people in one place. Their canoes would clutter the sea till there was no room.

And they could empty the sea each day of its fish and they would not all be

fed."

"So it would seem," Nam-Bok made final

answer; "yet it was so. With my own eyes I saw and flung my stick

away." He yawned heavily and rose to his feet. "I have paddled far.

The day has been long and I am tired. Now I will sleep, and to-morrow we will

have further talk upon the things I have seen."

Bask-Wah-Wan, hobbling fearfully in advance,

proud indeed, yet awed by her wonderful son, led him to her igloo, and

stowed him away among the greasy, ill-smelling furs. But the men lingered by

the fire, and a council was held wherein was there much whispering and

low-voiced discussion.

An hour passed, and a second, and Nam-Bok slept

and the talk went on. The evening sun dipped toward the northwest, and at

eleven at night was nearly due north. Then it was that the head man and the

bone-scratcher separated themselves from the council and aroused Nam-Bok. He

blinked up into their faces and turned on his side to sleep again. Opee-Kwan

gripped him by the arm and kindly but firmly shook his senses back to him.

"Come, Nam-Bok, arise!" he commanded.

"It be time."

"Another feast?" Nam-Bok cried.

"Nay, I am not hungry. Go on with the eating and let me sleep."

"Time to be gone!" Koogah

thundered.

"Time to be gone!" Koogah

thundered.

But Opee-Kwan spoke more softly. "Thou wast

bidarka-mate with me when we were boys," he said. "Together we first

chased the seal and drew the salmon from the traps. And thou didst drag me back

to life, Nam-Bok, when the sea closed over me, and I was sucked down to the

black rocks. Together we hungered and bore the chill of the frost, and together

we crawled beneath the one fur and lay close to each other. And because of

these things, and the kindness in which I stood to thee, it grieves me sore

that thou shouldst return such a remarkable liar. We cannot understand, and our

heads be dizzy with the things thou hast spoken. It is not good, and there has

been much talk in the council. Wherefore we send thee away, that our heads may

remain clear and strong, and be not troubled by the unaccountable

things."

"These things thou speakest of be

shadows," Koogah took up the strain. "From the shadow-world thou hast

brought them, and to the shadow-world thou must return them. Thy bidarka be

ready, and the tribespeople wait. They mey not sleep until thou art

gone."

Nam-Bok was perplexed, but hearkened to the voice

of the head man.

"If thou are Nam-Bok," Opee-Kwan was

saying, "thou art a fearful and most wonderful liar; if thou art the

shadow of Nam-Bok, then thou speakest of shadows, concerning which it is not

good that living men have knowledge. This great village thou has spoken of we

deem the village of shadows. Therein flutter the souls of the dead; for the

dead be many and the living few. The dead do not come back. Never have the dead

come back—save thou with thy wonder tales. It is not meet that the dead

come back, and should we permit it great trouble might be our

portion."

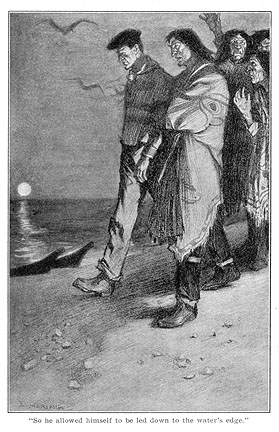

Nam-Bok knew is people well and was aware that

the voice of the council was supreme. So he allowed himself to be led down to the

water's edge, where he was put aboard his bidarka and a paddle thrust into his

hand. A stray wildfowl honked somewhere to seaward, and the surf broke limply

and hollowly on the sand. A dim twilight brooded over land and water, and in

the north the sun smoldered, vague and troubled, and draped about with

blood-red mists. The gulls were flying low. The off-shore wind blew keen and

chill, and the black-massed clouds behind it gave promise of bitter

weather.

"Out of the sea thou camest," Opee-Kwan

chanted, oracularly, "and back into the sea thou goest. Thus is balance

achieved and all things brought to law."

Bask-Wah-Wan limped to the froth mark and cried,

"I bless thee, Nam-Bok, for that thou has remembered me."

But Koogah, shoving Nam-Bok clear of the beach,

tore the shawl from her shoulders and flung it into the bidarka.

"It is cold in the long nights," she

wailed, "and the frost is prone to nip old bones."

"The thing is a shadow," the

bone-scratcher answered, "and shadows cannot keep thee warm."

Nam-Bok stood up that his voice might carry.

"O Bask-Wah-Wan, mother that bore me!" he called. "Hear to the

words of Nam-Bok. There be room in his bidarka for two, and he would that thou

come with him. For his journey is to where there are fish and oil in plenty.

There the frost comes not and life is easy, and the things of iron do the work

of men. Wilt thou come, O Bask-Wah-Wan?"

She debated a moment while the bidarka drifted

swiftly from her, then raised her voice to a quavering treble. "I am old,

Nam-Bok, and soon I shall pass down among the shadows. But I have no wish to go

before my time. I am old, Nam-Bok, and I am afraid."

A shaft of light shot across the dim-lit sea and

wrapped boat and man in a splendor of red and gold. Then a hush fell upon the

fisher-folk, and the only sounds were the moan of the off-shore wind and the

cries of the gulls flying low in the air.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.