Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

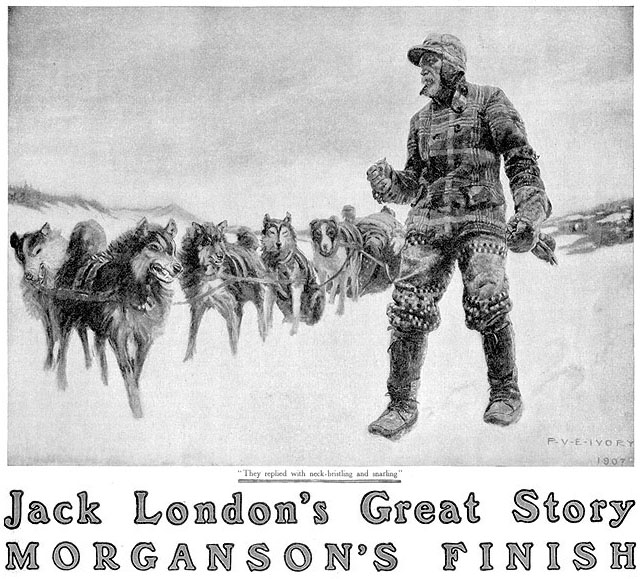

ILLUSTRATION BY P. V. E. IVORY

IT was the last of Morganson's bacon. He had begun with sopping his

biscuit in the grease on the bottom of the frying pan, and he had finished with

polishing the pan with the biscuit, licking with greedy lips the last drop of

the lukewarm grease, and ceasing reluctantly. Not that Morganson was a glutton,

but that the lean days into which he had fallen had reduced his pleasures to

the simple and animal-like. In all his life he had never pampered his stomach.

In fact, his stomach had been a sort of negligible quantity, that bothered him

little and about which he thought less. But now, in the long absence of wonted

delights, the keen yearning of his stomach was tickled hugely by the sharp,

salty bacon.

His face had a wistful, hungry expression. The

cheeks were hollow, and the skin seemed stretched a trifle tightly across the

cheek bones. His pale blue eyes were troubled. There was that in them that

showed the haunting imminence of something terrible. Doubt was in them, and

anxiety, and foreboding. The thin lips were thinner than they were made to be,

and they seemed to hunger toward the polished frying pan.

He sat back and drew forth a pipe. He looked into

it with sharp scrutiny, and tapped it emptily on his open palm. He turned the

hair-seal tobacco pouch inside out and dusted the lining, treasuring carefully

each flake and mite of tobacco that his efforts gleaned. The result was scarce

a thimbleful. He searched in his pockets, and brought forth, between thumb and

forefinger, tiny pinches of rubbish. Here and there in this rubbish were crumbs

of tobacco. These he segregated with microscopic care, though he occasionally

permitted small particles of foreign substance to accompany the crumbs to the

hoard in his palm. He even deliberately added small, semi-hard, woolly fluffs

that had come originally from the coat lining, and that had lain for long

months in the bottoms of the pockets.

At the end of fifteen minutes he had the pipe

part filled. He lighted it from the camp fire and sat forward on the blankets,

toasting his moccasined feet and smoking parsimoniously. When the pipe was

finished he sat on, brooding into the dying flame of the fire. Slowly the worry

went out of his eyes and resolve came in. Out of the chaos of his fortunes he

had finally achieved a way. But it was not a pretty way. His face had become

stern and wolfish, and the thin lips were drawn very tightly.

With resolve came action. He pulled himself

stiffly to his feet and proceeded to break camp. He packed the rolled blankets,

the frying pan, rifle, and ax, on the sled, and passed a lashing around the

load. Then he warmed his hands at the fire and pulled on his mittens. He was

foot-sore, and limped noticeably as he took his place at the head of the sled.

When he put the looped haul-rope over his shoulder and leaned his weight

against it to start the sled, he winced. His flesh was galled by many days of

contact with the haul-rope.

The trail led along the frozen breast of the

Yukon. It was a gray day, with a promise of snow in the heavy sky. To the south

there was a hint of brightness, and in that direction he limped at a rate of

two miles an hour. But he had not eyes for the day. They were fixed upon the

trail before him, and he stumbled on in habitual misery, as though he had been

doing this thing for a few centuries more or less. His mind was filled with

other thoughts, and his face grew harder. Now and again his lips tightened and

his eyes glowed somberly.

The trail led along the frozen breast of the

Yukon. It was a gray day, with a promise of snow in the heavy sky. To the south

there was a hint of brightness, and in that direction he limped at a rate of

two miles an hour. But he had not eyes for the day. They were fixed upon the

trail before him, and he stumbled on in habitual misery, as though he had been

doing this thing for a few centuries more or less. His mind was filled with

other thoughts, and his face grew harder. Now and again his lips tightened and

his eyes glowed somberly.

At the end of four hours he came around a bend

and entered the town of Minto. It was perched on top of a high earth bank, in

the midst of a clearing, and consisted of a road-house, a saloon, and several

cabins. He left his sled at the door and entered the saloon.

"Enough for a drink?" he asked, laying

an apparently empty gold sack upon the bar.

"The barkeeper looked sharply at it and him,

then set out a bottle and a glass.

"Never mind the dust," he said.

"Go on and take it," Morganson

insisted.

The barkeeper held the sack mouth downward over

the scales and shook it, and a few flakes of gold dust fell out. Morganson took

the sack from him, turned it inside out, and dusted it carefully.

"I thought there was half a dollar in

it," he said.

"Not quite," answered the other,

"but near enough. I'll get it back with the down-weight on the next

comer."

Morganson tilted the bottle and filled the glass

to the brim. He drank the liquor slowly, pleasuring in the fire of it that bit

his tongue, sank hotly down his throat, and with warm, gentle caresses

permeated his stomach. He was no more a drinker than he was a glutton. He had

never cared for whisky, had never known what it was to get drunk; but now that

life was lean he found easement and gratification in a mouthful of the fiery

liquid.

He sat and rested by the stove. Once he drew

forth a round, pocket looking-glass the size of a dollar, and by its aid, with

lifted lips, examined his mouth. The gums had a whitish appearance, as though

they had been scalded.

"Scurvy, eh?" the barkeeper asked.

"A touch of it," he answered. "But

I have n't begun to swell yet. Maybe I can get to Dyea and fresh vegetables and

beat it out."

"Kind of all in, I'd say," the other

laughed sympathetically. "No dogs, no money, and the scurvy. I'd try

spruce tea if I were you."

At the end of half an hour, Morganson said

good-by and left the saloon. He put his galled shoulder to the haul-rope and

took the river trail south. An hour later he halted. An inviting swale left the

river and led off to the right at an acute angle. He left his sled and limped

up the swale for half a mile. Between him and the river was a stretch of three

hundred yards of flat ground covered with cottonwoods. He crossed through the

cottonwoods to the bank of the Yukon. The trail went by just beneath, but he

did not descend to hit. He remained on top the bank and surveyed the situation

painstakingly. South, toward Selkirk, he could see the trail winding its sunken

length thorough the snow for over a mile. But to the north, in the direction of

Minto, a tree-covered out-jut in the bank a quarter of a mile away screened the

trail from him.

He seemed satisfied with the view, and returned

to the sled the way he had come. He put the haul-rope over his shoulder and

dragged the sled up the swale. The snow was unpacked and soft, and it was hard

work. The runners clogged and stuck, and he was panting severely ere he had

covered the half-mile. Night had come on by the time he had pitched his small

tent, set up the sheet-iron stove, and chopped a supply of firewood. He had no

candles, and contented himself with a pot of tea before crawling into his

blankets.

In the morning, as soon as he got up, he drew on

his mittens, pulled the flaps of his cap down over his ears, and crossed

through the cottonwoods to the Yukon. He took his rifle with him. As before, he

did not descend the bank. He watched the empty trail for an hour, beating his

hands and stamping his feet to keep up the circulation, then returned to the

tent for breakfast. There was little tea left in the canister—half a dozen

drawings at most; but so meager a pinch did he put in the teapot that he bade

fair to extend the lifetime of the tea indefinitely. His entire food supply

consisted of half a sack of flour and part-full can of baking powder. He made

biscuits, and ate them slowly, chewing each mouthful with infinite relish. When

he had eaten three he called a halt. He debated a while, reached for another

biscuit, then hesitated. He turned to the part sack of flour, lifted it, and

judged its weight.

"I'm good for a couple of weeks," he

spoke aloud.

"Maybe three," he added, as he put the

biscuits away.

Again he drew on his mittens, pulled down his

ear-flaps, took the rifle, and went out to his station on the river bank. He

crouched in the snow, himself unseen, and watched. After a few minutes of

inaction the frost began to bite in, and he rested the rifle across his knees

and beat his hands back and forth. Then the sting in his feet became

intolerable, and he stepped back from the bank and tramped heavily up and down

among the trees. But he did not tramp long at a time. Every several minutes he

came to the edge of the bank and peered up and down the trail. Besides, there

was little strength in him, and when he tramped over long he grew weak, and

panted and gasped, and stumbled. At such times he went back and sat down near

the bank.

But he could not sit long. Ever the cold drove

him tramping, and ever the tramping made him weak and drove him back to the

cold. Then there were the hunger pangs that made him restless, and that made

him sometimes stare with fierce intentness at the trail, as though by sheer

will he could materialize the form of a man upon it. The short morning passed,

though it had seemed century-long to him and the trail remained empty.

He went back to the tent, yearned toward the

biscuits, and built a fire in the stove. Waiting for the water to come to a

boil, he broke off a handful of the ends of young spruce boughs. While these

were steeping, he studied his mouth and gums in the looking-glass. The roof of

the mouth was quite white. He tried the teeth with pressures, but there was no

looseness. The gums still held.

It was easier in the afternoon, watching by the

bank. The temperature rose, and soon the snow began to fall—dry and fine and

crystalline. There was no wind, and it fell straight down, in quiet monotony.

He crouched with eyes closed, his head upon his knees, keeping his watch upon

the trail with his ears. But no whining of dogs, churning of sleds, nor cries

of drivers, broke the silence. With twilight he returned to the tent, cut a

supply of firewood, ate two biscuits, and crawled into his blankets. He slept

restlessly, tossing about and groaning; and at midnight he got up and ate

another biscuit.

The second day was a repetition of the first,

save that he suffered more from the cold. The snow had ceased, the sky had

cleared, and the temperature had fallen. And all day the trail stretched idly

in his vision like a dead thing that once had been alive.

Each day grew colder. Four biscuits could not

keep up the heat of his body, despite the quantities of hot spruce tea he

drank, and he increased his allowance, morning and evening, to three biscuits.

In the middle of the day he ate nothing, contenting himself with several cups

of excessively weak real tea. This programme became routine. In the morning

three biscuits, at noon real tea, and at night three biscuits. In between he

drank spruce tea for his scurvy. He caught himself making larger biscuits, and

after a sever struggle with himself went back to the old size.

On the fifth day the trail returned to life. To

the south a dark object appeared and grew larger. Morganson became alert. He

worked his rifle, ejecting a loaded cartridge from the chamber, by the same

action replacing it with another, and returning the ejected cartridge into the

magazine. He lowered the trigger to half-cock and drew on his mitten to keep

the trigger hand warm. As the dark object came nearer, he made it out to be a

man, without dogs or sled, traveling light. He grew nervous, cocked the

trigger, then put it back to half-cock again. The man developed into an Indian,

and Morganson, with a sigh of disappointment, dropped the rifle across his

knees. The Indian went on past and disappeared toward Minto behind the

outjutting clump of trees.

But Morganson had received an idea. He changed

his crouching spot to a place where cottonwood limbs projected on either side

of him. Into these, with his ax, he chopped two broad notches. Then in one of

the notches he rested the barrel of his rifle and glanced south along the

sights. He covered the trail thoroughly in that direction. He turned about,

rested the rifle in the other notch, and, looking along the sights, swept the

trail to the clump of trees behind which it disappeared. His lonely vigil

continued into the darkness, but the trail had died again.

At the end of the week he reduced his diet to two

biscuits morning and evening, and made up the difference by drinking more

spruce tea. But the latter did not stop the spread of his scurvy. The teeth

were still tight in their sockets, but his body had broken out in a dark and

bloody rash. There was nothing painful about it, and he realized that it was

the impurity of his blood working out through the skin. There were no signs of

swelling. He ceased studying his mouth in the looking-glass, and began to doubt

the efficacy of spruce tea.

He never descended to the trail. A man, traveling

the trail, could have no knowledge of his lurking presence on the bank above.

The snow surface was unbroken. There was no place where his tracks left the

main trail. As Morganson discovered, the snowfall had obliterated his sled

tracks half a mile below, where he had left the trail and gone up the swale.

When he learned this, he developed a plan whereby, in case of necessity, he

might leave and return without giving his hiding place away. Below the

outjutting clump of trees he had noticed an uprooted pine that overhung the

river trail. In fact, the trail passed under it, and he conceived the idea of

passing back and forth along the trunk of the pine tree.

As the nights grew longer, his periods of

daylight watching of the trail grew shorter. Once a sled went by with jingling

bells in the darkness, and with sullen resentment he chewed his biscuits and

listened to the sounds. Chance conspired against him. Faithfully he had watched

the trail for ten days, suffering from the cold all the prolonged torment of

the damned, and nothing had happened. Only an Indian, traveling light, had

passed in. Now, in the night, when it was impossible for him to watch, men and

dogs and a sled loaded with life, passed out, bound south to civilization.

So it was that he conceived of the sled for which

he waited. It was loaded with life, his life. His life was fading, fainting,

gasping away in the tent in the snow. He was weak from lack of food, and could

not travel of himself. But on the sled for which he waited were dogs that would

drag him, food that would fan up the flame of his life, money that would

furnish sea and sun and civilization. Sea and sun and civilization became terms

interchangeable with life, his life, and they were loaded there on the sled for

which he waited. The idea became an obsession, and he grew to think of himself

as the rightful and deprived owner of the sledload of life.

His flour was running short, and he went back to

two biscuits in the morning and two at night. Because of this his weakness

increased and the cold bit in more savagely, and day by day he watched by the

dead trail that would not live for him. At last the scurvy entered the next

stage. The skin, by means of the bloody rash, was unable longer to cast off the

impurity of the blood, and the result was that the body began to swell. His

ankles grew puffy, and the ache in them kept him awake long hours at night.

Then the swelling jumped to his knees, and the sum of his pain was more than

doubled.

Came a cold snap. THe temperature went down and

down—forty, fifty, sixty degrees below zero. He had no thermometer, but this

he knew by the signs and the natural phenomena understood by all men in the

country—the crackling of water thrown on the snow, the behavior of his spit

in the air, the swift sharpness of the bite of the frost, and the rapidity with

which his breath froze and coated the canvas walls and roof of the tent. Vainly

he fought the cold and strove to maintain his watch on the bank. In his weak

condition he was easy prey, and the frost sank its teeth deep into him before

he fled away to the tent and crouched by the fire. His nose and cheeks were

frozen and turned black, and his left thumb had frozen inside the mitten. The

latter he discovered when breaking a stick of kindling wood. His had slipped,

stick and thumb came violently together, and the sound it made was like the

sound of two sticks striking together. He forced a needle down through the numb

flesh in quest of sensation, and concluded that he would probably escape with

the loss of the first joint.

Then it was, beaten into the tent by the frost,

that the trail, with monstrous irony, suddenly teemed with life. Three sleds

went by the first day, and two the second. Once, during each day, he fought his

way out to the bank only to succumb and retreat, and each of the two times,

within half an hour after he retreated, a sled went by.

The cold snap broke, and he was able to remain by

the bank once more, and the trail died again. For a week, he crouched and

watched, and never life stirred along it, not a soul passed in or out. He had

cut down to one biscuit night and morning, and somehow he did not seem to

notice it. Sometimes he marveled at the way life remained in him. He would

never have thought it possible to endure so much.

Alone in the silent waste of white, crouching by

the bank and staring along the dead length of the trail, with the quiet,

pulseless cold eating into him and gnawing at his soul, he passed his life in

review before him, spending much time in his childhood, where the leanness of

living had not yet marred the perfection of the world. Also he went over and

over his futile two years' struggle for gold on the Yukon, minutely questioning

wherein he had been lazy or had wronged any man. And always he returned his own

verdict of not guilty. He had wronged no man. He had worked his hardest, worked

himself to skin and bone and helplessness. He was in the iron grip of

circumstance. His best laid plans had gone awry; his severest exertion had

returned him naught. He had missed a million by a minute in the stampede to

Finn Creek. Whose fault that one of his dogs had died in the harness and that

he had lost the minute—nay, two minutes—in cutting him out? It was the

malice of mischance, that was all, the malice of mischance.

When the trail fluttered anew with life, it was

life with which he could not cope. A detachment of Northwest Police went by, a

score of them, with many sleds and dogs, and he cowered down on the bank above,

and they were unaware of the menace of death that lurked in the form of a dying

man beside the trail.

One day his hunger mastered him. He became

hunger-mad, and ate ten biscuits. Only five pounds of flour remained to him,

and when he recovered his reason he penalized himself by not eating anything

for two days. But he smoked. When he had boiled all the essence out of his real

tea, he dried the leaves and smoked them in his pipe. The progress of his

ailment was whimsical. It attacked the muscles and joints and swelled on top of

one knee, and repeated the performance on the other knee but swelled underneath

it. As a result, one leg was permanently stiff, the other permanently bent. He

suffered severely when he rested his weight on them, but he continued to hobble

back and forth between the tent and the bank, and to hobble up and down in the

snow to keep warm.

His frozen thumb gave him a great deal of

trouble. The sloughing off of the joint was slow and painful, while the live

flesh that remained was unduly sensitive to the frost. While watching by the

bank he got into the habit of taking his mitten off and thrusting the hand

inside the shirt so as to rest the thumb in the warmth of his armpit. A mail

carrier came over the trail, and Morganson let him pass. A mail carrier was an

important person, and was sure to be immediately missed.

He had discontinued his practice of studying his

mouth in the looking-glass; but one day he looked into it. He never looked

again. He was frightened by the vision of himself. He had not thought his

cheeks were so hollow. The rough beard could not conceal these hollows, while

they were accentuated by the frost-blackened cheekbones above. But it was the

eyes and their ferocious wistfulness that gave him his fright. He was afraid of

himself, and, strive as he would, that vision of himself haunted him day and

night.

On the first day after his last flour had gone,

it snowed. It was always warm when the snow fell, and he sat out the whole

eight hours of daylight on the bank, without movement, terribly hungry and

terribly patient, for all the world like a monstrous spider waiting for its

prey. But the prey did not come, and he hobbled back to the tent through the

darkness, drank quarts of spruce tea and hot water, and went to bed.

The next morning circumstance eased its grip on

him. As he started to come out of the tent, he saw a huge bull moose crossing

the swale some four hundred yards away. Morganson felt a surge and bound of the

blood in him, and then went unaccountably weak. A nausea overpowered him, and

he was compelled to sit down a moment to recover. Then he reached for his rifle

and took careful aim. The first shot was a hit, he knew it; but the moose

turned and broke for the wooded hillside that came down to the swale.

Morganson pumped bullets wildly among the trees and brush at the fleeing

animal, until it dawned upon him that he was exhausting the ammunition he

needed for the sledload of life for which he waited.

He stopped shooting, and watched. He noted the

direction of the animal's flight, and, high up the hillside in an opening among

the trees, saw the trunk of a fallen pine. Continuing the moose's flight in his

mind, he saw that it must pass the trunk. He resolved on one more shot, and in

the empty air above the trunk he aimed and steadied his wavering rifle. The

animal sprang into his field of vision with lifted fore-legs as it took the

leap. He pulled the trigger. With the explosion the moose seemed to somersault

in the air. It crashed down to earth in the snow beyond and flurried the snow

into dust.

Morganson dashed up the hillside—at least he

started to dash up. The next he knew, he was coming out of a faint and dragging

himself to his feet. He went up more slowly, pausing from time to time to

breathe and to steady his reeling senses. At last he crawled over the trunk.

The moose lay still before him. He sat down heavily upon the carcass and

laughed. He buried his face in his mittened hands and laughed some more.

He shook the hysteria from him. He knew that the

carcass would soon freeze to the hardness of marble, and that before that time

he must cut it up. He drew his hunting knife and worked as rapidly as his

injured thumb and weakness would permit him. He did not stop to skin the moose,

but quartered it with its hide on. It was a Klondike of meat. As he worked he

estimated its weight at between eleven and twelve hundred pounds. And as he

worked he put pieces of fat in his mouth and sucked upon them for strength.

When he had finished, he selected a piece of meat

weighing a hundred pounds and started to drag it down to the tent. But the snow

was soft, and it was too much for him. He exchanged it for a twenty-pound

piece, and, with many pauses to rest, succeeded in getting it to the tent. He

fried some of the meat, but eat sparingly. Then, and

automatically, he went out to his crouching place on the bank. There were sled

tracks in the fresh snow on the trail, The sledload of

life had passed by while he was cutting up the moose.

But he did not mind. He was glad that the sled

had not passed before the coming of the moose. The moose had changed his plans.

Its meat was worth fifty cents a pound, and he was but little more than three

miles from Minto. He need no longer wait for a sledload of life. The moose was

the sledload of life. He would sell it. He would buy a couple of dogs at Minto,

some food, and some tobacco, and the dogs would haul him south along the trail

to the sea, the sun, and civilization.

He felt hungry. The dull, monotonous ache of

hunger had now become a sharp and insistent pang. He hobbled back to the tent

and fried a slice of meat. After that he smoked two whole pipefuls of dried tea

leaves. Then he fried another slice of moose. He was aware of an unwonted glow

of strength, and went out and chopped some firewood. He followed that up with a

slice of meat. Teased on by the food, his hunger grew into an inflammation. It

became imperative every little while to fry a slice of meat. He tried smaller

slices, and found himself frying oftener.

In the middle of the day he thought of the wild

animals that might eat his meat, and he climbed the hill, carrying along his

ax, the haul-rope, and a sled-lashing. In his weak state the making of the

cache and storing of the meat was an all-afternoon task. He cut young

saplings, trimmed them, and tied them together into a tall scaffold. It was not

so strong a cache as he would have desired to make, but he had done his

best. To hoist the meat to the top was heart-breaking. The larger pieces defied

him, until he passed the rope over a limb above, and, with one end fast to a

piece of meat, put all his weight on the other end. Even then, he failed when

he came to the largest piece, which weighed fully a hundred and fifty pounds.

It was heavier than he, and vainly he struggled with it. Faintness overpowered

him, and he went down to the tent and ate three slices of moose.

He returned up the hill strengthened and with an

idea. He made fast to the rope a hundred-pound piece of meat already on top the

cache. He pushed it off the scaffold, and, his own weight descending

with it, the one-hundred-and-fifty-pound piece arose. The trick was done. He

was quite proud of the idea, and it came to him that his condition was

improving or else he would not have it in him to be proud. Life was rosy to him

as he dragged his crippled body down through the darkness to the tent. The sea,

the sun, and civilization were very near.

Once in the tent, he proceeded to indulge in a

prolonged and solitary orgy. He did not need friends. His stomach and he were

company. Slice after slice and many slices of meat he fried and ate. He ate

pounds of the meat. He brewed real tea, and brewed it strong. He brewed the

last he had. It did not matter. On the morrow he would be buying tea in Minto.

When it seemed he could eat no more, he smoked. He smoked all his stock of

dried tea leaves. What of it? On the morrow he would be smoking tobacco. He

knocked out his pipe, fried a final slice, and went to bed. He had eaten so

much he seemed bursting; yet he had got out of his blankets and had just one

more mouthful of meat. He was glutted, and he slept like a gorged beast,

breathing stertorously, making little moaning cries as he suffered from the

weight of the meat.

In the morning he awoke as from the sleep of

death. In his ears were strange sounds. He id not know where he was, and looked

about him stupidly, until he caught sight of the frying pan with the last piece

of meat in it, partly eaten. Then he remembered all, and with a quick start

turned his attention to the strange sounds. He sprang from the blankets with an

oath. His scurvy-ravaged legs gave under him, and he winced with the pain. He

proceeded more slowly to put on his moccasins and leave the tent.

From the cache up the hillside arose a

confused noise of snapping and snarling, punctuated by occasional short, sharp

yelps. He increased his speed at much expense of pain, and cried loudly and

threateningly. He saw the wolves scurrying away through the snow and

underbrush, many of them, and he saw the scaffold down on the ground. The

animals were heavy with the meat they had eaten, and they were content to slink

away and leave him the wreckage. The way of the disaster was clear to him.

Moose and wolves were usually to be found together. The wolves had scented his

cache. One of them had leaped from the trunk of the fallen tree to the

top of the cache. He could see the marks of the brute's paws in the snow

that covered the trunk. He had not dreamed a wolf could leap so far. A second

had followed the first, and a third and fourth, until the flimsy scaffold had

gone down under their weight and movement.

His eyes were hard and savage for a moment as he

contemplated the extent of the calamity; then the old look of patience returned

into them, and he began to gather together the bones well picked and gnawed.

There was marrow in them, he knew; and also, here and there, as he sifted the

snow, he found even scraps of meat that had escaped the maws of the brutes made

careless by plenty.

He spent the rest of the morning dragging the

wreckage of the moose down the hillside. In addition, he had at least ten

pounds left of the chunk of meat he had dragged down the previous day.

"I'm good for weeks yet," was his

comment, as he surveyed the heap.

He had learned how to starve and live. He cleaned

his rifle and counted the cartridges that remained to him. There were seven. He

loaded the weapon and hobbled out to his crouching place on the bank. All day

he watched the dead trail. He watched all week, but no life passed over it. The

days continued to grow shorter. He knew that it must be near midwinter, though

he had no idea what day of the week or month it was, and he would not have been

surprised to see the days begin to lengthen.

What of the meat, he felt stronger, though his

scurvy was worse and more painful. He now lived upon soup, drinking endless

gallons of the thin product of the boiling of the moose bones. The soup grew

thinner and thinner as he cracked the bones and boiled them over and over; but

the hot water with the essence of the meat in it was good for him, and he was

more vigorous than he had been previous to the shooting of the moose.

During the next week of watching, one man came

over the trail. It was the mail carrier bound south. Morganson covered him with

the rifle the moment he appeared a quarter of a mile away; and while he plodded

that quarter of a mile, Morganson kept him covered with the rifle while he

debated with himself. In the end his reason won out, and he let the mail

carrier go by.

It was in this week that a new factor entered

into Morganson's life. He wanted to know the date. It became an obsession. He

pondered and calculated, but his conclusions were rarely the same. The first

thing in the morning and the last thing at night, and all day as well, watching

by the trail, he worried about it. He awoke at night and lay awake for hours

over the problem. To have known the date would have been of no value to him;

but his curiosity grew until it equaled his hunger and his desire to live.

Finally it mastered him, and he resolved to go to Minto and find out.

He left late in the afternoon, after fortifying

himself with a great quantity of very thin soup. By means of the overhanging

pine he had noted long before, he managed to leave his hiding place without

making any tracks. He climbed out the horizontal trunk and dropped down the

packed river trail. In his passage he had dislodged the snow that lay on top

the trunk; but he had prepared for this by bringing his ax along. He swung the

ax a few weak strokes, taking out several wide chips and marking the beginning

of a cut that would have gone through the trunk. He hid his ax in the snow

beside the trail and surveyed what he had done. The fresh chips and the

appearance of the cut looked as though some one had recently attempted to chop

the obstruction away. At the same time it accounted for the snow being knocked

off the top of the trunk.

It was dark when he arrived at Minto, but this

served him. No one saw him arrive. Besides, he knew that he would have

moonlight by which to return. He climbed the bank and pushed open the saloon

door. The light dazzled him. The source of it was several candles, but he had

been living for long in an unlighted tent. As his eyes adjusted themselves, he

saw three men sitting around the stove. They were tail travelers—he knew it

at once; and since they had not passed in, they were evidently bound out. They

would go by his tent next morning.

The barkeeper emitted a long and marveling

whistle.

"I thought you was dead," he said.

"Why?" Morganson asked, in a faltering

voice.

He had become unused to talking, and he was not

acquainted with the sound of his own voice. It seemed hoarse and strange.

"You 've ben dead for more 'n two

months, now," the barkeeper explained. ""You left here going

south, and you never arrived at Selkirk. Where have you ben?"

"Chopping wood for the steamboat

company," Morgan lied, unsteadily.

He was still trying to become acquainted with his

own voice. He hobbled across the floor and leaned against the bar. He knew he

must lie consistently; and, while he maintained an appearance of careless

indifference, his heart was beating and pounding furiously and irregularly, and

he could not help looking hungrily at the three men by the stove. They were the

possessors of life—his life.

"But where have you ben keeping yourself all

this time?" the barkeeper demanded.

"I located across the river a ways," he

answered. "I've got a mighty big stack of wood chopped."

The barkeeper nodded. His faced beamed with

understanding.

"I heard sounds of chopping several

times," he said. "So that was you, eh? Have a drink."

Morganson clutched the bar tightly. A drink! He

could have thrown his arms around the man's legs and kissed his feet. He tried

vainly to utter his acceptance; but the barkeep had not waited, and was already

passing out the bottle.

"But what did you do for grub?" the

latter asked. "You don't look as if you could chop enough wood to keep

yourself warm. You look terrible bad, friend."

Morganson yearned toward the delayed bottle and

gulped dryly.

"I did the chopping before the scurvy got

bad," he said. "Then I got a moose right at the start. I've been

living high all right. It's the scurvy that has run me down."

He filled the glass, and added, "But the

spruce tea's knocking it, I think."

"Have another," the barkeeper said.

The action of the two glasses of whisky on

Morganson's empty stomach and weak condition was rapid. The barkeeper's face

blurred before him, the candles danced and multiplied themselves, and he became

dizzy with the circulation of all the chaotic ideas he had thought but not

expressed during the lonely weeks of his torment. They surged around and around

inside his head, and seemed to have the consistency and weight and splash of

water. It was imperative that he should say them. He opened his mouth, but an

incoherent babbling poured out, and he laid his head on the bar and wept.

The next he knew he was sitting by the stove on a

box, and it seemed as though ages had passed. A tall, broad-shouldered,

black-whiskered man was paying for drinks. Morganson's swimming eyes saw him

drawing a greenback from a fat roll, and Morganson's swimming eyes cleared on

the instant. They were hundred-dollar bills. It was life! His life! He felt and

almost irresistible impulse to snatch the money and dash madly out into the

night.

The black-whiskered man and one of his companions

arose.

"Come on, Oleson," the former said to

the third one of the party, a fir-haired, ruddy-faced giant.

Oleson came to his feet, yawning and

stretching.

"What are you going to be so soon for?"

the barkeeper asked plaintively. "It's early yet.'

"Got to make Selkirk to-morrow," said

he of the black whiskers.

"On Christmas Day!" the barkeeper

cried.

"The better the day the better the

deed," the other laughed.

As the three men passed out the door, it came

dimly to Morganson that it was Christmas Eve. That was the date. That was what

he had come to Minto for. But it was overshadowed now by the three men

themselves, and the fat roll of hundred-dollar bills. The door slammed.

"That's Jack Thompson," the barkeeper

said. "Made two millions on Bonanza and Sulphur, and got more coming. I'm

going to bed. Have another drink first."

Morganson hesitated.

"A Christmas drink," the other urged.

"It's all right. I'll get it back when you sell your wood."

Morganson mastered his drunkenness long enough to

swallow the whisky, say good night, and get out on the trail. It was moonlight,

and he hobbled along through the bright, silvery quiet, with a vision of life

before him that took the form of a roll of hundred-dollar bills. The roll that

he saw was fluid, and even as he looked, it transformed itself into the salt

sea wind-ruffled, and flowed on into sunny, flower-vistaed landscapes, and into

great sounding cities of delight. He stumbled, and again the vision was a roll

of bills. His fingers made gripping movements inside his mittens, and he

clutched in the air for the roll; but it became a river of fresh vegetables and

green things to eat and that were good for scurvy. He pursued the vision and

floundered in the river of fresh green edibles, and came to himself in the soft

snow where he had gone off the trail. And as he regained the firmer footing,

the roll glimmered before him and flowed on and on in endless streams and seas

of delights and easements and satisfactions.

He awoke. It was dark, and he was in his

blankets. He had gone to bed in his moccasins and mittens, with the flaps of

his cap pulled down over his ears. He got up as quickly as his crippled

condition would permit, and built the fire and boiled some water. As he put the

spruce twigs into the teapot he noted the first glimmer of the pale morning

light. He caught up his rifle and hobbled in a panic out to the bank. As he

crouched and waited, it came to him that he had forgotten to drink his spruce

tea. The only other thought in his mind was the possibility of John Thompson

changing his mind and not traveling Christmas Day.

Dawn broke and merged into day. It was cold and

clear. Sixty below zero was Morganson's estimate of the frost. Not a breath

stirred the chill Arctic quiet. He sat up suddenly, his muscular tensity

increasing the hurt of the scurvy. He had heard the ar sound of a man's voice,

and the faint whining of dogs. He began beating his hands back and forth

against his sides. It was a serious matter to bar the trigger hand to sixty

degrees below zero, and against that time he needed to develop all the warmth

of which his flesh was capable.

They came into view around the out-jutting clump

of trees. To the fore was the third man, whose name he had not learned. Then

came eight dogs hauling the sled. At the front of the sled, guiding it by the

gee-pole, walked John Thompson. The rear was brought up by Oleson, the Swede.

He was certainly a fine, large man, Morganson thought, as he looked at the bulk

of him in his squirrel-skin parka. The men and dogs were silhouetted

sharply against the white of the landscape. They had the seeming of

two-dimension, cardboard figures that worked mechanically.

Morganson rested his cocked rifle in the notch in

the tree. As he glanced along the sights, men and dogs made a blur on the

trail. He looked away and looked back; they were still a blur. The landscape

seemed to swim, and quite distinctly he saw a wooded island down the river tilt

up to an angle of forty-five degrees and fall back again. He had not thought he

was so weak. He began to tremble violently. He took his right hand away from

the rifle for fear it might pull the trigger. A reeling blackness was welling

up in his consciousness. Then a thought flashed across his groping mind. The

memory came to him of the spruce tea he had made but had not drunk. It roused

him. He caught a vision of his wronged life and the havoc wrought by

circumstance, and a great coolness came upon him. He no longer trembled, and

his vision was clear again. Along the sights he could see the men

distinctly.

He became abruptly aware that his fingers were

cold, and discovered that his right hand was bare. He did not know that he had

taken off the mitten. He slipped it on again hastily. The men and dogs grew

closer, and he could see their breaths spouting into visibility in the cold

air. When the first man was fifty yards away, Morganson slipped the mitten from

this right hand. He placed the first finger on the trigger and aimed low. When

he fired, the first man whirled half around and went down on the trail.

In the instant of surprise, Morganson pulled

trigger on John Thompson—too low, for the latter staggered and sat down

suddenly on the sled. "In the stomach," was Morganson's thought, as

he raised his aim and fired again. John Thompson sank down backward along the

top of the loaded sled.

Morganson turned his attention to Oleson. At the

same time that he noted the latter running away toward Minto, he noted that the

dogs, coming to where the first man's body blocked the trail, had halted.

Morganson fired at the fleeing man and missed, and Oleson swerved. He continued

to swerve back and forth, while Morganson fired twice in rapid succession and

missed both shots. Morganson stopped himself just as he was pulling the trigger

again. He had fired six shots. Only one more cartridge remained, and it was in

the chamber. It was imperative that he should not miss his last shot.

He held his fire and desperately studied Oleson's

flight. The giant was grotesquely curving and twisting and running at top speed

along the trail, the tail of his parka flapping smartly behind.

Morganson trained his rifle on the man and with a swaying motion followed his

erratic flight. Morganson's finger was getting numb. He could scarcely feel the

trigger. "God help me," he breathed a prayer aloud, and pulled the

trigger. The running man pitched forward on his face, rebounded from the hard

trail, and slid along, rolling over and over. He threshed for a moment with his

arms and lay quiet.

Morganson dropped his rifle (worthless, now that

the last cartridge was gone) and slid down the bank through the soft snow. Now

that he had sprung the trap, concealment of his lurking place was no longer

necessary. He hobbled along the trail to the sled, his fingers making

involuntary gripping and clutching movements inside the mittens. The snarling

of the dogs halted him. The leader, a heavy dog, half Newfoundland and half

Hudson Bay, stood over the body of the man that lay on the trail, and menaced

Morganson with bristling hair and bared fangs. The other seven dogs of the team

were likewise bristling and snarling. Morganson approached tentatively, and the

team surged toward him. He stopped again, and talked to the animals,

threatening and cajoling by turns. He noticed the face of the man under the

leader's feet, and was surprised at how quickly it had turned white with the

ebb of life and the entrance of the frost. John Thompson lay back along the top

of the loaded sled, his head sunk in a space between two sacks and his chin

tilted upward, so that all Morganson could see was the black beard pointing

skyward.

FInding it impossible to face the dogs, Morganson

stepped off the trail into the deep snow and floundered in a wide circle to the

rear of the sled. Under the initiative of the leader, the team swung around in

its tangled harness. What of his cripple conditions, Morganson could move only

slowly. He saw the animals circling around on him, and tried to retreat. He

almost made it, but the big leader, with a savage lunge, sank its teeth into

the calf of his leg. The flesh was slashed and torn, but Morganson managed to

drag himself clear.

He cursed the brutes fiercely, but could not cow

them. They replied with neck-bristling and snarling, and with quick lunges

against their breastbands. He remembered Oleson, and turned his back upon them

and went along the trail. he scarcely took notice of his lacerated leg. It was

bleeding freely. The main artery had been torn, but he did not know it.

Especially remarkable to Morganson was the

extreme pallor of the Swede, who the preceding night had been so ruddy-faced.

Now his face was like white marble. What of his fair hair and lashes, he looked

like a carved statue rather than something that had been a man a few minutes

before. Morganson pulled off his mittens and searched the body. There was not

money belt around the waist next to the skin, nor did he find a gold sack. In a

breast pocket he found a small wallet. With fingers that swiftly went numb with

the frost, he hurried through the contents of the wallet. There were letters

with foreign stamps and postmarks on them, and several receipts and memorandum

accounts, and a letter of credit for eight hundred dollars. That was all. There

was no money.

He dropped the papers on the trail, slipped on

his mittens, and began beating his cold hands. For five minutes he did this,

when he felt the painful sting of the returning warmth. He saw the letter of

credit lying open on the snow, and he glanced back to the sled where John

Thompson lay securely guarded with his roll of hundred-dollar bills. Morganson

suddenly listened. He remembered his weary torment of waiting, and he seemed to

hear a great ironic laughter arising all around him in the silence. And

apprehensively he looked all around him, almost expecting to see the embodiment

of this thing that laughed. But he saw only the white landscape silent and cold

and motionless.

He made a movement to start back toward the sled,

but found his foot rooted to the trail. He glanced down and saw that he stood

in a fresh deposit of frozen red. There was red ice on his torn pants' leg and

on the moccasin beneath. With a quick effort he broke the frozen clutch of his

blood, and hobbled along the trail to the sled. The big leader that had bitten

him began snarling and lunging, and was followed in this conduct by the whole

team. Morganson wept weakly for a space, and weakly swayed from one side to the

other. Then he brushed away the frozen tears that gemmed his lashes. It was a

joke. Malicious chance was having its laugh at him. Even John Thompson, with

his heaven-aspiring whiskers, was laughing at him.

Morganson returned to the body of the Swede and

made a second search. He had found everything the first time, and the

"eight hundred dollars," written on the face of the letter of credit,

stared up and laughed at him from the snow. Then the silence about him began to

laugh. It was a terrible, silent laughter that made his senses reel, and he

turned and fled back to the living dogs that snarled and raged between him and

life, his life, that lay there on the sled.

He prowled around the sled demented, at times

weeping and pleading with the brutes for his life there on the sled, at other

times raging against them with blasphemous profanity. Then calmness came upon

him. He had been making a fool of himself. All he had to do was to go to the

tent, get the ax, and return and brain the dogs. He'd show them.

In order to get to the tent, he had to go wide of

the sled and the savage animals. He stepped off the trail into the soft snow.

Then he felt suddenly giddy, and stood still. He was afraid to go on for fear

he would fall down. He stood still for a long time, balancing himself on his

cripple legs that were trembling violently from weakness. He looked down and

saw the snow reddening at his feet. The blood flowed freely as ever. He had not

thought the bite was so sever. He controlled his giddiness and stooped to

examine the wound. The snow seemed rushing up to meet him, and he recoiled from

it as from a blow. He had a panic fear that he might fall down, and after a

struggle he managed to stand upright again. He was afraid of that snow that had

rushed up at him.

His giddiness increased, accompanied by nausea. A

suffocating blackness was rising up in his being and blotting him out. He beat

it down with all the strength of his his will. He could not see. Cobwebs formed

before his eyes, and vainly he tried to brush them away with his mittened hand.

His knees shook, and great weights seemed pressing him down into the

suffocating blackness. He was afraid to sit down. As by intuition, he feared

that he would never get up again. He would remain on his feet until the

giddiness had passed. Then he would attend to his wounded leg. So he stood

upright, swaying back and forth in the silence, and dreaming long dreams.

Between the dreams the world glimmered white through the cobwebs. And ever he

dreamed anew through the endless centuries, and swayed in the silence.

Then the white glimmer turned black, and the next

he knew he was awakening in the snow where he had fallen. He was no longer

giddy. The cobwebs were gone. But he could not get up. There was not strength

in his limbs. His body seemed lifeless. By a desperate effort he managed to

roll over on his side. In this position he caught a glimpse of the sled and of

John Thompson's black beard pointing skyward. Also he saw the lead-dog licking

the face of the man who lay on the trail. Morganson watched curiously. The dog

was nervous and eager. SOmetimes it uttered short, sharp yelps, as though to

arouse the man, and surveyed him with ears cocked forward and wagging tail. At

last it sat down, pointed its nose upward, and began to howl. Soon all the team

was howling.

Now that he was down, Morganson was no longer

afraid. He had a vision of himself being found dead in the snow, and for a

while he wept in self-pity. But he was not afraid. The struggle had gone out of

him. When he tried to open his eyes he found that the wet tears and frozen them

shut. He did not try to brush the ice away. It did not matter. Besides, he was

interested in his new state of consciousness—his lack of fear. He had not

dreamed death was so easy. He was even angry that he had struggled and suffered

through so many weeks. He had been bullied and cheated by the fear of death.

Death did not hurt. Every torment he had endured had been a torment of life.

Even the fear of death had been a torment of life—a like of life that was

jealous to live. Life had defamed death. It was a cruel thing.

But his anger passed. The lies and frauds of life

were of no consequence now that he was coming to his own. He became aware of

drowsiness, and felt a sweet sleep stealing upon him, balmy with promises of

easement and rest. He heard faintly the howling of the dogs, and had a fleeting

thought that in the mastering of his flesh the frost no longer bit. Then the

light and the thought ceased to pulse beneath the tear-gemmed eyelids, and with

a tired sigh of comfort he sank into sleep.

From the May, 1907 issue of Success Magazine

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.