Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() ANY

officers and men have I shaken hands with in the brief days since this wave of

war rolled south and broke on the shore of Mexico, and no officer nor man have

I found who was immune to a certain infection. This infection, however, might

be described in surgical jargon as "beneficent." On the face of it

every mother's son of them has told me something that cannot possibly be true.

Only one out of all of them could have told the truth, and it is beyond my

powers of discernment to pick out this man. But I have yet to meet an officer

of soldiers or marines who has not only solemnly assured me but with glistening

eyes of enthusiasm has averred that his regiment or battalion, officers and

men, for discipline and efficiency, is the finest in the entire army of the

United States. Furthermore, each one disclaims any personal prejudice in the

matter, and usually concludes with the statement that it is generally conceded

in army circles that his regiment or battalion is the finest. I wonder if such

esprit de corps exists in the Mexican army. What our army and navy is was

splendidly demonstrated when our bluejackets marched aboard their ships before

our drawn-up soldiers while Admiral Fletcher transferred the command of Vera

Cruz to General Funston. Boys they were, all boys, the flower of the young men

of our land, and they marched with the clacking rhythm of "boots,

boots" on the pavement along the broad lane formed by the regulars on one

side presenting arms and on the other side cheering American civilians. It was

a joy to see the faces that tried not to smile with pleasure over the applause

for work well done, and to catch the involuntary sideward glances of boyish

eyes not yet quite disciplined to the level impassive look of war.

ANY

officers and men have I shaken hands with in the brief days since this wave of

war rolled south and broke on the shore of Mexico, and no officer nor man have

I found who was immune to a certain infection. This infection, however, might

be described in surgical jargon as "beneficent." On the face of it

every mother's son of them has told me something that cannot possibly be true.

Only one out of all of them could have told the truth, and it is beyond my

powers of discernment to pick out this man. But I have yet to meet an officer

of soldiers or marines who has not only solemnly assured me but with glistening

eyes of enthusiasm has averred that his regiment or battalion, officers and

men, for discipline and efficiency, is the finest in the entire army of the

United States. Furthermore, each one disclaims any personal prejudice in the

matter, and usually concludes with the statement that it is generally conceded

in army circles that his regiment or battalion is the finest. I wonder if such

esprit de corps exists in the Mexican army. What our army and navy is was

splendidly demonstrated when our bluejackets marched aboard their ships before

our drawn-up soldiers while Admiral Fletcher transferred the command of Vera

Cruz to General Funston. Boys they were, all boys, the flower of the young men

of our land, and they marched with the clacking rhythm of "boots,

boots" on the pavement along the broad lane formed by the regulars on one

side presenting arms and on the other side cheering American civilians. It was

a joy to see the faces that tried not to smile with pleasure over the applause

for work well done, and to catch the involuntary sideward glances of boyish

eyes not yet quite disciplined to the level impassive look of war.

These thousands of sailors marched straight down

the dock end and disappeared. The effect was uncanny. What was becoming of

them? The smokestacks of a couple of tugs showed at the dock end, and that was

all. And yet the river of men flowed on and on, sailors and marines, officers,

bands, hospital squads, and moving banners, sun-tanned men of the

Arkansas, the Florida, the Utah, the San Francisco,

the New Hampshire, the South Carolina, the Vermont, the

Chester, and the New Jersey, all without a hitch or halt, and

disappeared. It reminded one of the tank of the New York Hippodrome, when the

long lines of stage soldiers march down into the water, knee-high, hip-high,

shoulder-high, then heads under and are gone.

But out at the dock end, besides the tugs, was a

flotilla of launches and cutters that received those thousands as fast as they

arrived and carried them at a single trip to the battleships lying in the inner

and outer harbors.

Two Types of "Gringo" Fighting Men

OUR

soldiers and sailors are markedly different in type. It must be curious how

this happens to be so. Do land life and sea life make the difference? Or does

one common type of man elect the sea and another common type elect the land?

The sailors are shorter, broader shouldered, thicker set. The soldiers are

taller, leaner, longer legged. Their faces are leaner, their lips thinner. They

seem to the eye tougher, stringier, sterner. The sailors' faces seem broader

across the cheek bones. Their lips seem fuller, their bodies more rounded.

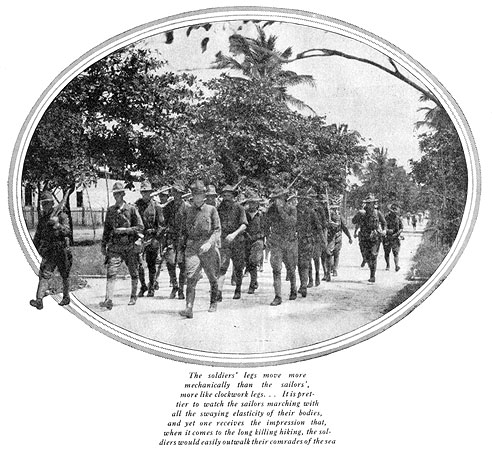

Most notable is the difference when they are

grouped into marching masses. The sailors have a swinging, springing, elastic

stride. The soldiers' legs move more mechanically, more like clockwork legs,

with a very tiny minimum of waste motion. It is prettier to watch the sailors

marching with all the swaying elasticity of their bodies, and yet one receives

the impression that, when it comes to the long killing hiking, the soldiers

would easily outwalk their comrades of the sea. A great throng of Mexicans,

numbers of them without a doubt having sniped our sailors during the first

days, looked on this display of what manner of men we send to war. The haste

and advertisement with which they doffed their hats to the Stars and Stripes

was absurd and laughable.

One cannot but imagine what the situation would

be like were it reversed—were Vera Cruz populated by Americans and in the

possession of a Mexican army. First of all, our jefe politico, or mayor, would

have been taken out and shot against a wall. Against walls all over the city

our oldiers and civilians would have been lined up and shot. Our jails would

have been emptied of criminals, who would be made soldiers and looters. No

American's life would be safe, especially if he were known to possess any

money. Law, save for harshest military law, such as has been meted out by

conquerors since the human world began, would have ceased. So would all

business have ceased. He who possessed food would hide it, and there would be

hungry women and children.

Quite the contrary has been our occupation of

Vera Cruz. To the amazement of the Mexicans, there was no general slaughter

against blank walls. Instead of turning the prisoners loose, their numbers were

added to. Every riotous and disorderly citizen, every sneak thief and petty

offender, was marched to the city prison the moment he displayed activity. The

American conquerors bid for the old order that had obtained in the city, and

began the bidding by putting the petty offenders to sweeping the streets.

No property was confiscated. Anything

commandeered for the use of the army was paid for, and well paid for. Men who

owned horses, mules, carts, and automobiles competed with one another to have

their property commandeered. The graft which all business men suffered at the

hands of their own officials immediately ceased. Never in their lives had their

property been so safe and so profitable. Incidentally, the diseases that stalk

at the heels of war did not stalk. On the contrary, Vera Cruz was cleaned and

disinfected as it had never been in all its history.

The Various Benefits of Being Conquered

IN

SHORT, American occupation gave Vera Cruz a bull market in health, order, and

business. Mexican paper money appreciated. Prices rose. Profits soared. Verily,

the Vera Cruzans will long remember this being conquered by the Americans, and

yearn for the blissful day when the Americans will conquer them again. They

would not mind thus being conquered to the end of time.

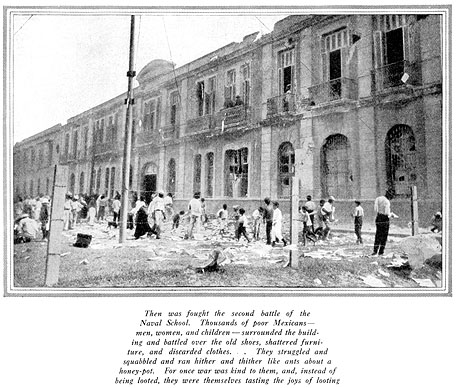

An exciting sight was the cleaning up

of the Naval School, which had been so disorganized the first day by the five

minutes of shell fire from the Chester. Immediately the city had been

turned over to the army by the navy, the first battalion of the Fourth Infantry

and Fourth Field Artillery descended upon the Naval School. In a trice every

window was vomiting forth the débris that clogged the interior. And then

was fought the second battle of the Naval School. Thousands of poor

Mexicans—men, women, and children—surrounded the building and battled over

the old shoes, shattered furniture, and discarded clothes. It was the women who

fought fiercest and most vociferously, and, to the accompaniment of much hair

pulling, many a pair of linen trousers and its legs irrevocably separated. They

struggled and squabbled and ran hither and thither like ants about a honey-pot.

For once war was kind to them, and, instead of being looted, they were

themselves tasting the joys of looting. And alas! I saw the ruined pretties

rain down amid the mortar dust from my lady's boudoir and the two red,

high-heeled Spanish slippers borne off in opposite directions by gleeful Indian

women.

An exciting sight was the cleaning up

of the Naval School, which had been so disorganized the first day by the five

minutes of shell fire from the Chester. Immediately the city had been

turned over to the army by the navy, the first battalion of the Fourth Infantry

and Fourth Field Artillery descended upon the Naval School. In a trice every

window was vomiting forth the débris that clogged the interior. And then

was fought the second battle of the Naval School. Thousands of poor

Mexicans—men, women, and children—surrounded the building and battled over

the old shoes, shattered furniture, and discarded clothes. It was the women who

fought fiercest and most vociferously, and, to the accompaniment of much hair

pulling, many a pair of linen trousers and its legs irrevocably separated. They

struggled and squabbled and ran hither and thither like ants about a honey-pot.

For once war was kind to them, and, instead of being looted, they were

themselves tasting the joys of looting. And alas! I saw the ruined pretties

rain down amid the mortar dust from my lady's boudoir and the two red,

high-heeled Spanish slippers borne off in opposite directions by gleeful Indian

women.

Fighting Qualities of the Peon

AS I

write this, beneath my window, with a great clattering of hoofs on the asphalt,

is passing a long column of mountain batteries, all carried on the backs of our

big Government mules. And as I look down at our sun-bronzed troopers in their

olive drab, my mind reverts to the review the other day of our soldiers and

sailors. Surely, if the peon soldiers of Mexico could have been brought down to

witness what manner of soldiers and equipment was ours, there would have been

such a rush for the brush that ten years would not have seen the last of them

dug out of their hiding places.

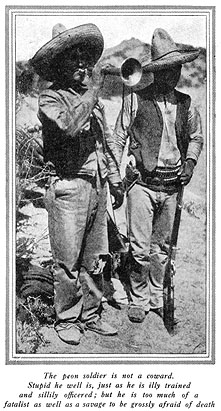

And yet this is not fair. The peon soldier is not

a coward. Stupid he well is, just as sillily officered; but he is too much of a

fatalist as well as a savage to be grossly afraid of death. The peon bends to

the mailed fist of power, but never breaks. Like the fellah of Egypt, he

patiently endures through the centuries and watches his rulers come and go.

Changes of government mean to the peon merely

changes of the everlasting master. His harsh treatment and poorly rewarded toil

are ever the same, unchanging as the sun and seasons. He has little to lose and

less to gain. He is born to an unlovely place in life. It is the will of God,

the law of existence.

With rare exceptions he does not dream that there

may be a social order wherein can be no masters of the sort he knows. He has

always been a slave. He was a slave to the Toltecs and the Aztecs, to the

Spaniards, and to the Mexicans descended from the Aztecs and the Spaniards. It

must not be concluded that there is no hope for him in the future. He is what

he is to-day, and what he has been for so long, because he has been made so by

a cruel and ruthless selection.

The Elimination of the Spirited

IF A

breeder should stock his farm with the swiftest race horses obtainable, and

employ a method of selection whereby only the slowest and clumsiest horses were

bred, it would not be many generations before he would have a breed of very

slow and very clumsy horses. Life is plastic and varies in all directions.

Occasionally this breeder would find a beautiful, swift colt born on his farm.

Since kind begets kind, he would eliminate such a colt and perpetuate only the

slow and clumsy.

Now this is just the sort of selection that has

been applied to the peon for many centuries. Whenever a peon of dream and

passion and vision and spirit was born he was eliminated. His masters wanted

lowly, docile, stupid slaves, and resented such a variation. Soon or late the

spirit of such a peon manifested itself and the peon was shot or flogged to

death. He did not beget. His kind perished with him whenever he appeared.

But life is plastic and can be molded by

selection into diverse forms. The horse breeder can reverse his method of

selection, and from slow and clumsy sires and dams bred up a strain of horses

beautiful and swift. And so with the peon. For the present generation of him

there is little hope. But for the future generations a social selection that

will put a premium of living on dream and passion and vision and spirit will

develop an entirely different type of peon.

A Soldier Against His Will

BUT

we must not make the mistake of straying after far goals. The time is now. We

live now. Our problem, the world problem, the peon problem is now. The peon we

must consider is the peon as he is now—the selected burden bearer of the

centuries. He has never heard of economic principles, nor a square deal. Nor

has he thrilled, save vaguely, to the call of freedom—in which even freedom

has meant license, and, as robber and bandit, he has treated the weak and

defenseless in precisely the same way he has been accustomed to begin

treated.

I was through a Mexican barracks. It was like a

jail. All the windows were barred. They had to be barred so that the conscript

peon soldiers might not escape. Most of them do not like to be soldiers. They

are compelled to be. All over Mexico they gather the peons into the jails and

force them to become soldiers. Sometimes they are arrested for petty

infractions of the law. A peon seeks to gladden his existence by drinking a few

cents' worth of half-spoiled pulque. The maggots of intoxication begin to crawl

in his brain, and he is happy in that for a space he has forgotten in God knows

what dim drunken imaginings. Then the long arm of his ruler reaches out through

the medium of many minions, and the peon, sober with an aching head, finds

himself in jail waiting the next draft to the army. Often enough he does not

have to commit any petty infraction. He is railroaded to the front just the

same.

He does not know whom he fight for, for what, or

why. He accepts it as the system of life. It is a very sad world, but it is the

only world he knows. This is why he is not altogether a coward in battle. Also

it is why, in the midst of battle or afterward, he so frequently changes sides.

He is not fighting for any principle, for any reward. It is a sad

world, in which witless, humble men are just forced to fight, to kill, and to

be killed. The merits of either banner are equal, or, rather, so far as he is

concerned, there are no merits to either banner.

He is not fighting for any principle, for any reward. It is a sad

world, in which witless, humble men are just forced to fight, to kill, and to

be killed. The merits of either banner are equal, or, rather, so far as he is

concerned, there are no merits to either banner.

He prays to God in some dim, dumb way, and

vaguely imagines when he has been expedited from this sad world by a machete

slash or bayonet thrust or high-velocity steel-jacketed bullet that all will be

made square in that other world where God rules and where taskmasters are

not.

Yet, deep down in the true ribs of him, there is

a vein of raw savagery in the peon. Of old he delighted in human sacrifice.

To-day he delights in the not always skilled butchery of bulls in the game

introduced by his late Spanish masters. He likes cock-fighting with curved

steel spurs that slash to the heart of life and cast a crimson splash upon the

dull gray of living.

His Fatalism

AND

still the peon is not exposited. There is another side to him. He is a born

gambler, as well as fatalist, and he is not averse to taking a chance; though

his own life be the stake, he plays against another's life. How else can be

explained his nervy conduct, deserted by his officers, in defending Vera Cruz

against our landing forces?

Now I am not altogether a coward. I have ever

been guilty on occasion of taking a chance. And yet I am frank to say that I

would not dream of taking a chance on the flat roofs of Vera Cruz against

thousands of American soldiers and a fleet of battleships with an effective

range of five thousand yards.

But this was the very chance many a peon soldier

took. He sniped our men from the roofs in the fond hope that he could kill a

man and escape being killed himself. Also, he was stupid in that he did not

realized how little chance he had. Nevertheless, and on top of it all, he was

not afraid.

They say that he and his fellows even dared to

crawl unwounded, amid the wounded, into the hospital cots under the Red Cross,

and to draw blankets over themselves and the Mausers, and to crawl out

occasionally to the roofs for another shot at our sailors. When it became too

hot for them they hid among the wounded again. Now this is a deed too risky for

my nerve or for the nerve of any intelligent man. But I insist that these

Mexican soldiers were stupid enough voluntarily to take the chance. From this

another conclusion may be draw, namely, that the sorry soldier of Mexico is not

altogether amiable and is prone to be nasty and dangerous to the American boys

who have crossed the sea to take "peaceable" possession of a

customhouse.

I saw the leg of a peon soldier amputated. It was

a perfectly good leg, all except for a few inches of bone near the thigh which

had been shattered to countless fragments by a wobbling, high-velocity American

bullet. And as I gazed at that leg, limp yet with life, being carried out of

the operating room, and realized that this was what men did to men in the

twentieth century after Christ, I found myself in accord of sentiment with the

peon: it is a sad world, a sad world!

An Example of Swift Destruction

IT

IS a sad world wherein the millions of the stupid lowly are compelled to toil

and moil at the making of all manner of commodities that can be and are on

occasion destroyed in an instant by the hot breath of war. I have just come

back from the vast Cuartel, or Barracks, of Vera Cruz. Such a destruction of

the labor of men! Bales upon bales and mountains of bales of clothing, of

uniforms of wool, of linen, of cotton, disrupted, torn to pieces, scattered

about, infected by possible diseases that compel a final cleansing by fire.

Huge squad rooms, knee-deep in the litter of things the toil of men has

made—hats, caps, shirts, modern leather shoes and rude sandals of the sort

worn on the north Mediterranean half a thousand years before the days of Julius

Cæsar; saddles and saddle bags, spurs, bridles, and bits; entrenching

tools, scattered contents of soldiers' ditty boxes, canteens and mess kits of

tin, serapes from the north, mats from the hot countries, meals partly eaten,

half-cooked messes of food in the kitchen pots, smashed Mausers, cymbals and

tubes, drums and cornets of a brass band that had departed abruptly and

bandless.

In the manner of a few minutes the feet of war

had trod under foot and passed on. Those who fled had fled hastily, leaving

their last-issued rations behind. Those who pursued had paused but long enough

to fire a myriad of shots and race on. The empty bandoliers marked the trail of

the American sailors and marines. In the stables were the officers' automobiles

and carromatas with seats for grooms behind. But there were no horses, and the

automobiles had been smashed. Thousands of hours' toil of men's hands had been

annihilated.

The streets of Vera Cruz teem with beggars. Our

soldiers are pestered by the starving, ragged poor. A thousand meals cluttered

the Cuartel, already mildewed and being eaten by cockroaches and stray cats;

woven cloth and manufactured footgear sufficient for ten thousand poor were

destined for the flames. I agree with the peon: It is a sad world. It is also a

funny world.

A Square Deal?

THE query inevitably rises: How is the peon to get a square deal? And who will give him a square deal? By square deal is not meant the Utopian ideal dreamed of a far future, but the measure of fair treatment that is possible here and now in civilized nations. The men of the civilized nations are only frail, fallible, human men, with all the weaknesses common to human men just in the process of emerging from barbarism. Nevertheless, with such men a squarer deal obtains than does obtain in savagery. The much-mixed descendants of the Spaniards and Aztecs can scarcely be called civilized. They have had over four centuries of rule in Mexico, and they have done anything but build a civilization. What measure of civilization they do possess is exotic. It has been introduced by north Europeans and Americans, and by north Europeans and Americans has it been maintained. The peon of to-day, under Mexican rule, is no better off than he was under Aztec rule. It is to be doubted that he is as well off. On the face of it, his much-mixed breed of rulers cannot give him the square deal that is possible to be given by more intelligent and humane rulers—that is given to-day by such rulers in other countries in the world.

Motes and Beams

Of course, the owner of a horse, when arrested by

an agent of a humane society, indignantly protests that the horse is his

property. But a wider social vision is growing in the foremost nations that

property rights are a social responsibility, and that society can and must

interfere between the owner and his mismanaged property. But somehow the old

order is hard to change. There is a narcotic mangle in phrases and precedents.

It is an established right for society to step in between a man and his horse,

but it is still abhorrent for a nation to step in between a handful of rulers

and their millions of mismanaged and ill-treated subjects. Yet such

interference is logically the duty of the United States as the big brother of

the countries of the New World. Nevertheless, the United States did so step in

when it went to war with Spain over the ill treatment of the Cubans. But is

required the blowing up of the Maine to precipitate its action.

AND

here in Mexico the United States has stepped in, still dominated by narcotic

precedent, on the immediate pretext of a failure in formal courtesy about a

flag. But why not have done with fooling? Why not toss the old drugs overboard

and consider the matter clear-eyed? The exotic civilization introduced by

America and Europe is being destroyed by the madness of a handful of rulers who

do not know how to rule, who have never successfully ruled, and whose orgies at

ruling have been and are similar to those indulged in by drunken miners sowing

the floors of barrooms with their fortunate gold dust.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.

The mixed-breed rulers of Mexico seem incapable

of treating the peon with the measure of fairness that is possible in the world

to-day and that is practiced the world to-day. The Mexican peon residing in the

United States at the present time—and there are many thousands of him—is far

better treated than are his brothers south of the border.

Never mind what his legal status may be or is

alleged to be. The fact is, the peon of Mexico, so far as liberty and a share

in the happiness produced by his toil is concerned, is as much a slave as he

ever was. He is so much property to his rulers, who work him, not with

treatment equal to that a accorded a horse, but with harsher and far less

considerate treatment.

Big Brother's Job

The big brother can police, organize, and manage

Mexico. The so-called leaders of Mexico cannot. And the lives and happiness of

a few million peons, as well as of many millions yet to be born, are at

stake.

The policeman stops a man from beating his wife.

The humane officer stops a man from beating his horse. May not a powerful and

self-alleged enlightened nation stop a handful of inefficient and incapable

rulers from making a shambles and a desert of a fair land wherein are all the

natural resources of a high and happy civilization?

From the May 39, 1914 issue of Collier's magazine.