Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() HE bronze

clangor of the cathedral bells marks the hours. Out of the night day bursts

with an abruptness of light and of birdcalls. Newsboys' voices announce the

first editions of Mexican morning papers and the fall of Tampico. There are dog

yelps, the rattle and grind of big-wheeled mule carts, a clatter of cavalry

hoofs on the asphalt, bugle calls, and Vera Cruz has begun another day.

HE bronze

clangor of the cathedral bells marks the hours. Out of the night day bursts

with an abruptness of light and of birdcalls. Newsboys' voices announce the

first editions of Mexican morning papers and the fall of Tampico. There are dog

yelps, the rattle and grind of big-wheeled mule carts, a clatter of cavalry

hoofs on the asphalt, bugle calls, and Vera Cruz has begun another day.

Bareheaded women, betraying little of Spanish and

much of Indian in their faces, pass on their way to market. Cargadores slither

by on leather sandals, and peddlers carrying their stocks in trade on their

heads. Spigotty police, in wrinkled linen uniforms, swing their clubs

valiantly, and, in contrast with our husky sentries of the regular army, appear

pathetically small of stature, pinched of chest, and narrow of shoulder. And in

the cathedral Indians and mixed breeds pray to the gods and saints of their

believing, perplexed by the incomprehensible situation of their beloved city in

the possession of armed white-skinned men from over the sea.

These natives of Mexico have never possessed more

than a skeleton of law. They were two entire ethnic periods behind the Spanish

when Cortes landed his mail-clad adventurers on their shore. And Cortes and the

generations of acquisitive adventurers that followed him, themselves no genius

for government, intermarried with the Indian population and made no

improvements in government.

Improvised Proconsuls

PRIMITIVE

government is simple, religious, and rigid. When the Indian governmental

machinery was thrown out of gear, with here and there a smashed cog, lacking in

plasticity, the millions of Indians fell an easy prey to the Spanish

conquistadores. The compromise, resulting from the blending of a people

backward in governmental development with a people unpossessed of the genius

for government, brought about the weak and inefficient government that has been

Mexico's for the last four centuries.

Come now, in the year 1914, from the United

States, the white-skinned armed men with an inherited genius for government.

Here is Vera Cruz with a population of 30,000; here, in addition, there are

thousands of American soldiers and thousands of American and Mexican refugees

from the interior. Problem: how to get these many thousands up out of bed in

the morning and to work or play; how to get them home and to bed at night, all

in decent and orderly fashion.

There must be safety for all. They must not

quarrel with one another. They must keep themselves clean and the city clean.

They must pursue the multifarious activities by which only can a city exist.

They must not hurt one another, either by theft or violence, or by squalidly

cultivating infection. And they must not even hurt, by excess of cruelty, the

scrubby four-legged creatures that are their draft animals.

And the thing is done, decency and order made to

reign, and all by the white-skinned fighting men who know how to rule as well

as fight. Never, in the long history of Vera Cruz, has the city been so decent,

so orderly, so safe, so clean. And it is accomplished, not by civilians from

the United States, but by soldiers from the United States, and it is done

without graft.

Captain Turner of the Seventh Infantry makes the

following interesting announcement in the Mexican newspapers:

"As I have taken charge of the

administration of the State taxes for this canton, by order of the Provost

Marshal General, I beg to advise the public that from the seventh day of this

month this office will proceed with its usual business under my orders.

"The public is hereby advised that persons

who have not paid up taxes on city property which were due on the thirtieth day

of April, 1914, will be allowed until the twenty-fifth day of the present month

in which to pay them; but if any or all of them are not paid by the date

mentioned above the property will be subject to the usual legal

processes."

Comes Major Miller, his sword for the time being

laid aside while he serves as chief of the Department of Education, with this

advertisement:

"Professors and teachers formerly employed

in the public schools of Vera Cruz, and who have not already signified their

intention to resume work, but who desire to do so, and others who are qualified

to teach and desire such employment, are requested to make application to this

department. The latter class of applicants should present proper credentials

and proof of qualification."

Also, Major Miller announces that the Biblioteca

del Publico will reopen on May 20.

Colonel Plummer of the Twenty-eighth Infantry

advertises that the sale of cocaine and marihuana is prohibited except on a

doctor's prescription, and that violation of this order will be severely

punished. Since Colonel Plummer is Provost Marshal General, his advertisements

include all sorts of prohibitions, from spitting on sidewalks and in public

places to warning shopkeepers not to extend credit to soldiers, and pawnbrokers

not to receive pledges of Government property.

General Funston serves notice that every

inhabitant of Vera Cruz must forthwith be vaccinated.

The Business of Justice

THE work of war is not forgotten. The lines of outposts and trenches circle the city; the waterworks are protected; the hydroplanes scout overhead; and night and day, on lookout and in the trenches, men and officers stand their regular shifts. But, inside the lines, colonels and majors, captains and first lieutenants turn their hands to governing and operating the Departments of Law, Public Work, Public Safety, Finance, and Education. Then there is the Military Commission, with powers of life and death, grimly sitting on the cases of persons charged with infractions of the Laws of Hostile Occupation and the Laws of War. Further, there are four Inferior Provost Courts and one Superior Provost Court sitting regularly every day. The jurisdiction of the Provost Court is limited to criminal cases, and these courts are far from idle.

The Captain-Judge in Action

THE

ordinary citizen in any city at home may pursue his routine of life for days,

weeks, and months, and see nothing out of the way or disorderly. And yet, day

and night, and all days and nights, disorderly acts will have taken place and

the many offenders will have been combed by the police from the riffraff of the

city and brought before the courts.

Vera Cruz, at the present time, despite its

military occupation, has all the seeming of such a city. All is quiet and

seemly on the streets, where just the other day men were killing one another on

the sidewalks and housetops. The very spigotty police, known, some of them, to

have engaged in sniping our men, have been put back to work under our army

administration. And yet, for a city of this size, more than the usual combing

of the riffraff is necessary. It is the desire of the military government,

among other things, to rid the city of all able-bodied loafers, whether Mexican

or foreign. If Mexican, they are sent out through the lines; if foreign, they

are deported to their respective countries. On the other hand, there is nothing

hasty in this cavalier treatment.  Petty offenders continually receive dismissals

or suspended sentences for first offences. Nor is the right to be represented

by counsel denied anyone.

Petty offenders continually receive dismissals

or suspended sentences for first offences. Nor is the right to be represented

by counsel denied anyone.

A visit to the Inferior Provost Court in the

Municipal Palace proved most illuminating. Here, at a desk across which flowed

a steady stream of documents, in olive-drab shirt and riding trousers, with a

.45 automatic at his hip, sat a blond lawgiver, taken from the command of his

company in the Nineteenth Infantry to administer the law of Mexico and the

orders, above Mexican law, which have been issued by the Provost Marshal

General.

At the desk beside the Captain-Judge, an enlisted

man, in uniform, pounded a typewriter, kept a record of decisions, fines,

imprisonments, and probations, and performed the rest of the tasks of a

police-court clerk. Soldiers clacked across the square marble flags of the

court-room floor, and came and went, carrying messages, appearing and

disappearing through high doorways and under broad arches. In one corner a

soldier telegrapher operated an army telegraph.

Strapping soldiers, with bayonets fixed, guarded

the doorway that led both to freedom and to the cells. Between these guards,

small people, furtive or sullen, came and went—if witnesses, summoned from

without by an alert little spigotty bailiff; if prisoners, escorted by armed

soldiers.

"Tell the Lady She Was Drunk," Says the Court

AS IS usual

with our police courts at home, not one but many cases are going on

simultaneously. A fresh witness in a case of theft, sent for half an hour

before, arrives and gives evidence between the payment of a fine and the

fuddled protestations of an Indian woman that she was not drunk the preceding

evening. While the court interpreter has halted the testimony of a suspected

fence in order to look up in the dictionary the English equivalent for a

Spanish phrase the Captain-Judge admonishes a hotel keeper on the conduct of

his house, dispatches a policeman to bring into court two pairs of stolen

trousers evidently germane to some other case that is somehow in process of

being tried, and listens to the remarks of a Spanish lawyer appearing for some

man not yet brought from the cells.

The stream of many cases thins for a moment, and

the Captain-Judge, who has the bluest of blue eyes and the fairest of fair

hair, calls the name, "Francisco Ibanez de Paralta."

A peon, covered with rags for the price of which

six cents would be an extortion, shambles up and bows humbly.

"Tell him that he was drunk and disorderly

on the street last night," the Captain-Judge says to the interpreter.

This being duly communicated, the culprit makes

brief reply, which is translated by the interpreter as: "That's right. He

says he was drunk all right and is sorry."

"Has he steady work?" asked the

Captain-Judge.

"No. He says he is a cargador and works when

he can."

"Tell him if he is brought here again he

will be given sixteen days—turn him loose," is the verdict.

Next appears Serafina Cruz. She is blear-eyed and

semicomatose.

"Tell the lady she was drunk again

yesterday," says the Court to the interpreter.

Serafina acknowledges the soft impeachment with a

"Si," a nod, and a yawn.

"Second offense, sixteen days in which to

sober up—she needs it," is the Court's judgment, and Sefafina is trailed

away to the cells by a big American soldier.

Maria and the Handcart

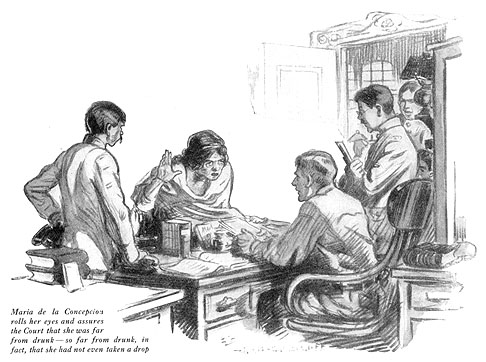

MARIA DE LA

CONCEPCION DE HENRIQUEZ, a gentle-faced, soft-voiced woman whose ancestors, by

the tokens of race in her face, pronounced their names by means of many Aztec

"z's" and "x's," denies flatly that she was drunk the

preceding morning. The arresting spigotty officer, being duly sworn, deposes

that she was so drunk that he was compelled to transport her to the lockup in a

handcart. Maria de la Concepcion assures the Court that the arresting officer

is a dog and worse than a dog; he is the broken mustaches of a gutter cat, a

grubless buzzard, a wingless pelican; that the truth is not in him; and,

furthermore, that she was not drunk.

Captain Callahan, a blond Celt in American

uniform, taking oath, affirms that he did see the lady arrive, dead drunk, in a

handcart propelled by the aforesaid spigotty policeman.

Maria de la Concepcion rolls her eyes in an

expression of grieved shock at such unveracity on the part of such a

gentlemanly appearing American gentleman, and assures the Court that she was

far from drunk—so far from drunk, in fact, that she had not taken even a

drop.

The patient Captain-Judge settles the matter out

of hand.

"Tell her," he commands the

interpreter, "that it happens I saw her myself when she was brought in on

the handcart. Ask her where is her home."

Back, via the interpreter, comes the information

that she has no home.

"First offense—five days—what is the

matter with that man?" says the Captain-Judge all in one breath.

"That man," from his bright, keen,

elderly face, evidently is not a drunk. Also, in his face there are no signs of

evil, so one wonders what he has done.

His name is José de Garro, the interpreter

says for him. During the days of street fighting, while he lay hid, the United

States sailors made use of his handcart, which happens to be his sole means of

livelihood. He has now discovered his handcart. It is being used by the

servants of the proprietor of the Hotel Diligencia, and said proprietor has

declined to return it to him.

The Court does not ponder the matter.

Like the crack of a whiplash, his orders are issued:

The Court does not ponder the matter.

Like the crack of a whiplash, his orders are issued:

"Send a policeman to the Hotel Diligencia

and bring the handcart and the proprietor here. Find from the complainant two

men who will swear to his identity and to his ownership of the handcart, and

send a policemen to bring the two men he names. Mercedes de

Villagran!"

While Mercedes de Villagran is being brought from

the cells, two thieves, Messrs. Bravo de Saravio and Pedro Sorez de Ulloa,

already sent for and just brought from the cells, are considered. Captain

Callahan is interrogated by the Court from without through an open window, and

Captain Callahan's information causes the Court to command that the two thieves

be remanded, the case being grave, and be kept incommunicado waiting the

evidence in process of being gathered.

His Name Upon His Arm

MERCEDES DE

VILLAGRAN proves to be a wizened little old woman, very worn, very miserable,

very frightened, who is charged with having in her possession munitions of war.

Worst of all, a double handful of Mauser cartridges is exhibited in evidence.

In a thin, quavering falsetto she explains that after the street fighting,

pursuing her regular vocation of garbage picking, she did find and retain

possession of the munitions of war, deeming them of value and unaware that

possession of them constituted a grave offense or any offense at all.

"Case dismissed—turn her loose," and

the captain-judge has forgotten her on the instant and forever in

the thick rush of his crowded life, but him she will ever remember, to her last

breath, in her chatter of gossip with her garbage-picking sisters of Vera

Cruz.

A prisoner is called, whose entry on the docket

causes the Court's brows to corrugate; for the man has no name, and is entered

as "P," with a note to the effect that Captain Callahan will

explain.

Captain Callahan, not for the moment findable,

possibly engaged in receiving another lady in a handcart, the Court tries two

more cases of drunk, one, a second offense, receiving sixteen days and a

warning that on a third offense he will be sent out through the lines.

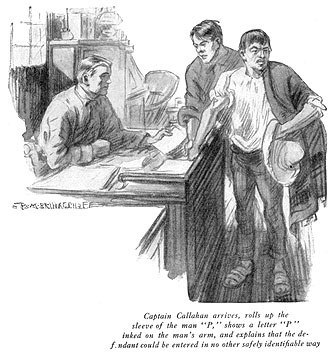

Captain Callahan arrives, rolls up the sleeve of

the man "P," shows a letter "P" inked on the man's arm, and

explains that the defendant, arriving at jail so hopelessly drunk as to be

speechless, could be entered in no other safely identifiable way, wherefore he

had inked the man's arm, and there was the proof of it. Mr. "P,"

somewhat recovered after a night's sleep, is able to state that his name is

Alonzo de Codova y Figueroa. The soldier clerk, remembering the face and

searching the record, announces that Alonze de Codova y Figueroa is a

second-timer, and Alonze de Codova y Figueroa, in debt to the United States

with his time to the extent of sixteen days, is taken away.

Patience, Swiftness, and Certitude

THE

handcart, the proprietor of the Hotel Diligencia, and the policeman arrive in

high garrulity. The proprietor is a squat, stoop-shouldered, pock-marked,

white-haired Cuban, whose state of mind is one of amazement in that the

handcart, on which he never laid eyes before, should have been found on his

premises.

The handcart man looks on his property with joy,

and cannot understand why the Captain-Judge does not immediately permit him to

take it away, while the Captain-Judge receives particulars of a house raid the

previous night in which four Mausers and a thousand rounds of ammunition had

been unearthed.

Appears Tomas Martin de Poveda, charged with the

ghastly crime of maintaining unclean premises. After a brief lecture on hygiene

and sanitation, the Court gives the culprit twenty-four hours in which to clean

up, and Thomas Martin de Poveda departs, shaking his had at such administration

of justice by the thrice lunatice gringos.

A shopkeeper and a cigar maker arrive, take oath,

and testify that José de Garro is truly José de Garro and that

the handcart is truly his property, and José de Garro goes on his way

rejoicing that God's still in heaven and justice in Vera Cruz.

The cases of three thieves, charged with stealing

from the customhouse, and of a fence who bought the stolen property, are

inquired into and continued. Follows a Jamaica negro cook and a cockney steward

from an English steamer, jointly charged with stealing a gold watch from a

Spanish refugee.

The Court interrogates all three, discharges the

negro, holds the cockney for trial, and dispatches a summons for the master of

the ship to appear in court next morning, accompanied by a polite request first

to search the cockney's belongings on board ship.

More men are warned for maintaining

unclean premises; and one man, for having struck his wife, a dark-skinned,

bovine-eyed Indian Madonna who testifies reluctantly, receives ten days, and is

thunderstruck that such maladministration of justice can be. A thin-face widow,

in a blight of black, pays the fine of her roistering eldest born, who, while

crazed with several centavos' worth of ninety-proof aguardiente, demolished a

window and portions of the anatomy of a spigotty policeman. The Captain-Judge

has seen service in Cuba, Porto Rico, and the Philippines, and his

"Carabao English," so learned, stands him in good stead. Not merely

on occasion, but on many occasions, he corrects and checks the interpreter when

that worthy fails properly to interpret shades of meaning or engages in

animated discussions with prisoners and witnesses on irrelevant topics. Another

thing that characterized the efficiency of this blond lawgiver of a regular

army captain, whose ancestors must have been more than closely related to

Hengist and Horsa, is his combined patience, swiftness, and certitude. Rough

and ready his justice is, but legal always, and unswayed by the seriousness or

lightness of any case. He opposes directness and simplicity to the garrulity

and immateriality of the Vera Cruzans. His patient questions go to the point,

he achieves his conclusion in the midst of some longwinded explanation of

things concerning other things and not the things at issue, and suddenly, like

a shot, he enunciates his decision: "I find you guilty—forty days";

or: "Not guilty—next case."

More men are warned for maintaining

unclean premises; and one man, for having struck his wife, a dark-skinned,

bovine-eyed Indian Madonna who testifies reluctantly, receives ten days, and is

thunderstruck that such maladministration of justice can be. A thin-face widow,

in a blight of black, pays the fine of her roistering eldest born, who, while

crazed with several centavos' worth of ninety-proof aguardiente, demolished a

window and portions of the anatomy of a spigotty policeman. The Captain-Judge

has seen service in Cuba, Porto Rico, and the Philippines, and his

"Carabao English," so learned, stands him in good stead. Not merely

on occasion, but on many occasions, he corrects and checks the interpreter when

that worthy fails properly to interpret shades of meaning or engages in

animated discussions with prisoners and witnesses on irrelevant topics. Another

thing that characterized the efficiency of this blond lawgiver of a regular

army captain, whose ancestors must have been more than closely related to

Hengist and Horsa, is his combined patience, swiftness, and certitude. Rough

and ready his justice is, but legal always, and unswayed by the seriousness or

lightness of any case. He opposes directness and simplicity to the garrulity

and immateriality of the Vera Cruzans. His patient questions go to the point,

he achieves his conclusion in the midst of some longwinded explanation of

things concerning other things and not the things at issue, and suddenly, like

a shot, he enunciates his decision: "I find you guilty—forty days";

or: "Not guilty—next case."

Sentencing a Leech

HE finds

Martin Onez de Loyola, a full-blooded Spaniard, guilty of a particularly mean

crime and sentences him to six months—this merely to hold him until he can be

deported to his native country, which is Spain. But the Captain-Judge is

thorough. He gives instructions that when the convicted man is deported the

Chief of Police of Barcelona be warned to nab him when he disembarks on his

native soil.

This case of Martin Onez de Loyola merits the

harshness of the sentence. A well-to-do but ignorant Mexican woman of the

capital had married her deceased husband's brother, equally well-to-do and

ignorant. Loyola, becoming aware of the matter, had assured them hat it was a

terrible crime, and had bled them, at different times, of over ten thousand

pesos. In order to escape him they had started to flee the country; but Loyola,

true leech that he was, followed them through the lines of two hostile armies

to Vera Cruz. And so, thanks to the Captain-Judge, they were able to return to

Mexico, while their persecutor, willy-nilly, made the voyage to Spain.

Franisco Hernandez, trouble-eyed and stupid,

charged with stealing a barrel of wine, positively declares himself not guilty,

and the patient Court unravels the tangle. Pedro de Valvidia, owner of a

cantina, and his barkeeper, Garcia de Mendoza, testify to catching the thief in

the act and to apprehending him with the barrel already rolled out on the

sidewalk and merrily rolling onward.

He Stole a Barrel

TWO peon

witnesses testify to having seen Francisco Hernandez captured while rolling the

barrel, and the case begins to look dark for Francisco Hernandez, who has

pleaded non guilty. But he receives inspiration. He acknowledges all the facts

testified to. He was not the owner of the barrel. He did go into the cantina

and roll out the barrel. He was caught by the owner and barkeeper in the manner

described, but—and he makes the explanation that is as ancient as the first

theft of portable property—it happened that as he came along the street

looking for a job, his profession being that of a cargador, two strange men

approached him and hired him to convey the barrel of wine, which they had just

purchased, to their residence. That was all. He was innocent as a new-born

babe. What did he want with a whole barrel of wine? What could he

do with a whole barrel of wine, being a temperate as well as an honest man?

"Where were you going to deliver the

barrel?" the Court demands.

Francisco Hernandez somehow cannot remember the

address.

"Who were the men?"

Francisco Hernandez says they were strangers.

"Describe them."

And one can actually see Francisco Hernandez's

imagination working at high pressure as he paints the portraits of the two

mythical strangers.

The Court asks several other questions not very

important, merely concerning his whereabouts earlier in the day and how often

he succeeded in getting work, and Francisco Hernandez, believing that his tale

is believed, grows confident.

"Describe the two men," the Court

suddenly commands.

The Case of Rosalia

POOR

Hernandez is taken by surprise. He stumbles and halts, tries to remember his

extempore description of the two individuals, diverges, slips up, falls down,

and, in the midst of his gropings and stutterings, is astounded to hear the

Captain-Judge decisively utter just three words: "Guilty—six

months." And while the interpreter is transposing this misfortune into

understandable Spanish terms, the Captain-Judge is already into the thick of

the next case.

And this is a case destined to make the entire

native population of Vera Cruz sit up and take notice that never was similar

justice dispensed before, albeit 4,000 soldiers and 20,000 marines and

bluejackets, to say nothing of $100,000,000 worth of warships, were required to

install the Captain-Judge in the Municipal Palace.

It is a sordid, squalid case. Rosalia de Xara

Quemada and Cristovel de la Cerda are the culprits. Alonzo de Xara Quemada is

the husband of Rosalia, and is also the complainant. He is a bulgy-eyed,

cadaverous-cheeked, vulpine-faced individual, and he grins vindictively and

triumphantly as he makes his charge.

Rosalia is frightened and dumbly defiant. She has

a full, oval face, wavy brown hair parted in the middle and neatly bound with a

light blue ribbon, and dangling earrings. There is just sufficient Spanish in

the Indian of her to give her temperament and to account for the inimitable

draping of the brown shawl about her shoulders and hips. Cristovel, the lover,

is a depressed and gloomy young man who keeps books for a living.

A Judgment of Solomon

ROSALIA and

Cristovel plead guilty, and are prepared for merciless judgment at the hands of

the Captain-Judge who transacts justice with a big automatic at his hip and

with armed soldiers for his attendants. But the Captain-Judge is not satisfied.

He asks Rosalia and her husband, Alonzo, many penetrating questions. They have

five children. For four years Alonzo has not contributed a centavo toward their

support. Rosalia, by scrubbing, by peddling, by cooking, and by various other

ways has given the entire support to her brood of five.

As all this comes out, Rosalia seems to take

heart of courage and grows voluble, while Alonzo glowers at her in a way that

would bode a beating were there none present to interfere. The reason her

husband had had her arrested, Rosalia volunteers, was that just previous to the

arrest she had refuse to lend him five pesos. At other times in the past she

had loaned him money. No, he had never returned a single loan.

The Captain-Judge orders the culprits to step

forward to receive sentence, knits his brow for a moment in thought, and

proceeds:

"Cristovel de la Cerda. You have pleaded

guilty of the grave offense of adultery. By the Mexican law of this State I

could sentence you to two years. But I shall not be harsh. I shall sentence you

to six months. The sentence, however, will be suspended and I release you here

and now on probation. You will report to this court every Saturday morning at

nine o'clock with a letter from your employer attesting your good

behavior."

As the interpreter turns this into Spanish, the

husband's face is a rich study. At the mention of two years, it is hilarious.

The six months' sentence leaves it sill hilarious, but not so hilarious. The

suspension of the sentence positively floors Alonzo, and the angry blood surges

darkly under his skin.

"There Is No Mexican Law Here"

ROSALIA is

similarly sentenced, released on probation, told to report every Saturday

morning, and admonished to be good. But the case is not over. Alonzo de Xara

Quemada, distraught with this frightful miscarriage of justice, is ordered to

stand forth.

"Alonzo de Xara Quemada, your conduct has

been most reprehensible."

While the interpreter struggles with the

dictionary for the Spanish equivalent of the introductory sentence, Alonzo

looks as if he expects to be backed up against a wall the next moment and

shot.

"These five children are yours just as much

as they are Rosalia's. From now on you shall do your share toward supporting

them. Each week you shall pay to Rosalia the sum of five pesos. Each Saturday

morning at nine o'clock you shall appear before me with the receipt for the

five pesos. If you don't, we will see what six months in jail will do for

you."

The whole thing is too unthinkably hideous for

Alonzo. He blows up, and in impassioned language forswears and disowns Rosalia,

the five children, and all memory of them and responsibility for them, forever

and forever. Furthermore, he will not pay the weekly five pesos. Who ever heard

of such a thing? He denies the Captain-Judge's right in the matter, and all in

wild harangue announces that he will appeal to the Mexican courts against such

injustice.

Whereupon the Captain-Judge's fist comes down on

the desk, and the Captain-Judge thunders:

"There is no Mexican law here. I am the law.

You will pay the five pesos. To-day is Thursday. Next Saturday you will appear

before me with the receipt for the first five pesos. Vamos."

Alonzo de Xara Quemada starts to protests, but

two soldiers, with wicked-looking bayonets on the ends of their rifles, step

forward, and Alonzo subsided.

A Moving Picture

I DEPARTED on

his heels, greedily enjoying the maledictions he muttered down the street. And

on Saturday morning I made it a point to be present at the Provost Court at

nine o'clock. Sure enough, Alonzo de Xara Quemada was there, sullenly

exhibiting a receipt for five pesos signed by one Rosalia de Xara Quemada.

And all the affairs and transactions I have

described in this article constitute but a portion of one morning's work in one

Provost Court of the five Provost Courts sitting in Vera Cruz.

Before I cease, I cannot forbear describing a

little scene I witnessed right after Alonzo's plaint had died away down the

street. Captain Callahan was engaged in receiving a lady who was more difficult

to receive than if she had come in a handcart. A sweaty and disheveled spigotty

policeman had brought her, and she had fought him all the way to such effect

that he stood near the entrance to the cells too exhausted to move her a step

further. In vain Captain Callahan ordered him to proceed with her. She was the

stronger, and she had caught her second wind. Just as she flung herself on the

policeman in savage onslaught, a big American soldier strode to her and tapped

her authoritatively on the arm. She turned and stared up at him. He spoke no

word, but with a curt thrust of his thumb over his shoulder indicated the way

to the cells. She wilted into all meekness and obedience, and meekly and

obediently, without a hand being laid on her, walked into the cell room.

From the June 20, 1914 issue of Collier's magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.