By Jack London

ECAUSE

we are sick, they take away our liberty. We have obeyed the law. We have done

no wrong. And yet they would put us in prison. Molokai is a prison. That you

know. Niuli, there, his sister was sent to Molokai seven years ago. He has not

seen her since. Nor will he ever see her. She must stay there until she dies.

This is not her will. It is not Niuli's will. It is the will of the white men

who rule the land. And who are these white men?

ECAUSE

we are sick, they take away our liberty. We have obeyed the law. We have done

no wrong. And yet they would put us in prison. Molokai is a prison. That you

know. Niuli, there, his sister was sent to Molokai seven years ago. He has not

seen her since. Nor will he ever see her. She must stay there until she dies.

This is not her will. It is not Niuli's will. It is the will of the white men

who rule the land. And who are these white men?

"Let us not make trouble," he began.

"We ask to be left alone. But if they do not leave us alone, then is the

trouble theirs, and the penalty. My fingers are gone, as you see." He held

up his stumps of hands that all might see. "Yet have I the joint of one

thumb left, and it can pull a trigger as firmly as did its lost neighbor in the

old days. We love Kauai. Let us live here, or die here, but do not let us go to

the prisons of Molokai. The sickness is not ours. We have not sinned. The men

who preached the word of God and the word of Rum brought the sickness with the

coolie slaves who work the stolen land. I have been a judge. I know the law and

the justice, and I say to you it is unjust to steal a man's land, to make that

man sick with the Chinese sickness, and then to put that man in prison for

life."

"Life is short, and the days are filled with

pain," said Koolau. "Let us drink and dance and be happy as we

can."

From one of the rocky lairs calabashes were

produced and passed around. The calabashes were filled with the fierce

distillation of the root of the ti-plant; and as the liquid fire coursed

through them and mounted to their brains, they forgot that they had once been

men and women, for they were men and women once more. The woman who wept

scalding tears from open eye-pits, was indeed a woman apulse with life as she

plucked the strings of a ukulele and lifted her voice in a barbaric

love-call such as might have come from the dark forest-depths of the primeval

world. The air tingled with her cry, softly imperious and seductive. Upon a

mat, timing his rhythm to the woman's song, Kiloliana danced. It was

unmistakable. Love danced in all his movements, and, next, dancing with him on

the mat, was a woman, whose heavy hips and generous breast gave the lie to her

disease-corroded face. It was a dance of the living dead, for in their

disintegrating bodies life still loved and longed. Ever the woman whose

sightless eyes ran scalding tears changed her love-cry, ever the dancers danced

the love in the warm night, and ever the calabashes went around till in all

their brains were maggots crawling of memory and desire. And with the woman on

the mat danced a slender maid whose face was beautiful and unmarred, but whose

twisted arms that rose and fell marked the disease's ravage. And the two

idiots, gibbering and mouthing strange noises, danced apart, grotesque,

fantastic, travestying love as they themselves had been travestied by life.

But the woman's love-cry broke midway, the

calabashes were lowered, and the dancers ceased, as all gazed into the abyss

above the sea, where a rocket flared like a wan phantom through the moonlit

air.

"It is the soldiers," said Koolau.

"Tomorrow there will be fighting. It is well to sleep and be

prepared."

The lepers obeyed, crawling away to their lairs

in the cliff, until only Koolau remained, sitting motionless in the moonlight,

a statue, his rifle across his knees, as he gazed far down to the boats landing

on the beach.

The far head of Kalalau Valley had been well

chosen as a refuge. Except Kiloliana, who knew back-trails up the precipitous

walls, no man could win to the gorge save by advancing across a knife-edged

ridge. This passage was a hundred yards in length. At best, it was a scant

twelve inches wide. A slip, and to right or left the man would fall to his

death. But once across he would find himself in an earthly paradise. A sea of

vegetation laved the landscape, pouring its green billows from wall to wall,

dripping from the cliff-lips in great vine-masses and flinging a spray of ferns

and air-plants into the multitudinous crevices. During the many months of

Koolau's rule, he and his followers had fought with this vegetable sea. The

choking jungle, with its riot of blossoms, had been driven back from the

bananas, oranges and mangoes that grew wild. In little clearings grew the wild

arrow-root; on stone terraces, filled with soil-scrapings, were the

taro-patches and the melons; and in every open space where the sunshine

penetrated, were papaia-trees burdened with their golden fruit.

Koolau had been driven to this refuge from the

lower valley by the beach. And if he were driven from it in turn, he knew of

gorges among the jumbled peaks of the inner fastnesses where he could lead his

subjects and live. And now he lay with his rifle beside him, peering down

through a tangled screen of foliage at the soldiers on the beach. He noted that

they had large guns with them, from which the sunshine flashed as from mirrors.

The knife-edged passage lay directly before him. Crawling upward along the

trail that led to it, he could see tiny specks of men. He knew they were not

soldiers but the police. When they failed, then the soldiers would enter the

game.

He affectionately rubbed a twisted hand along his

rifle-barrel and made sure that the sights were clean. He had learned to shoot

as a wild-cattle hunter on Niihau, and on that island his skill as a marksman

was unforgotten. As the toiling specks of men grew nearer and larger, he

estimated the range, judged the deflection of the wind that swept at

right-angles across the line of fire, and calculated the chances of

overshooting marks that were so far below his level. But he did not shoot. Not

until they reached the beginning of the passage did he make his presence known.

He did not disclose himself, but spoke from the thicket.

"What do you want?" he demanded.

"We want Koolau, the leper," answered

the man who led the native police, himself a blue-eyed American.

"You must go back," Koolau said.

He knew the man, a deputy sheriff, for it was by

him that he had been harried out of Niihau, across Kauai, to Kalalau Valley,

and out of the valley to the gorge.

"Who are you?" the sheriff asked.

"I am Koolau, the leper," was the

reply.

"Then come out. We want you. Dead or alive,

there is a thousand dollars on your head. You cannot escape."

Koolau laughed aloud in the thicket.

"Come out!" the sheriff commanded, and

was answered by silence.

He conferred with the police, and Koolau saw that

they were preparing to rush him.

"Koolau," the sheriff called.

"Koolau, I am coming across to get you."

"Then look first and well about you at the

sun and sea and sky, for it will be the last time you behold them."

"That 's all right, Koolau," the

sheriff said soothingly. "I know you 're a dead shot. But you wont

shoot me. I have never done you any wrong."

Koolau grunted in the thicket.

"I say, you know, I 've never done you

any wrong, have I?" the sheriff persisted.

"You do me wrong when you try to put me in

prison," was the reply. "And you do me wrong when you try for the

thousand dollars on my head. If you will live, stay where you are."

"I 've got to come across and get you.

I'm sorry. But it is my duty."

"You will die before you get

across."

The sheriff was no coward. Yet was he undecided.

He gazed into the gulf on either side and ran his eyes along the knife-edge he

must travel. Then he made up his mind.

"Koolau," he called.

But the thicket remained silent.

"Koolau, dont shoot. I am coming."

The sheriff turned, gave some orders to the

police, then started on his perilous way. He advanced slowly. It was like

walking a tight-rope. He had nothing to lean upon by air. The lava-rock

crumbled under his feet, and on either side the dislodged fragments pitched

downward through the depths. The sun blazed upon him, and his face was wet with

sweat. Still he advanced, until the half-way point was reached.

"Stop!" Koolau commanded from the

thicket. "One more step and I shoot."

The sheriff halted, swaying for balance as he

stood poised above the void. His face was pale, but his eyes were determined.

He licked his dry lips before he spoke.

"Koolau, you wont shoot me. I know you

wont."

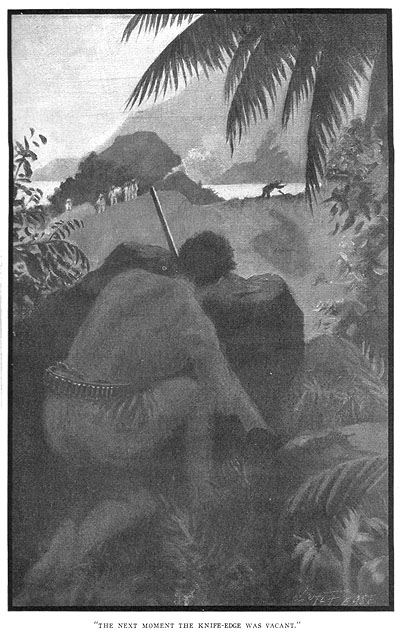

He started once more. The bullet whirled him

half-about. On his face was an expression of querulous surprise as he reeled to

the fall. He tried to save himself by throwing his body across the knife-edge;

but at that moment he knew death. The next moment the knife-edge was vacant.

Then came the rush, five policemen, in single file, with superb steadiness,

running along the knife-edge. At the same instant the rest of the posse opened

fire on the thicket. It was madness. Five times Koolau pulled the trigger, so

rapidly that his shots constituted a rattle. Changing his position and

crouching low under the bullets that were biting and singing through the

bushes, he peered out. Four of the police had followed the sheriff. The fifth

lay across the knife-edge, still alive. On the farther side, no longer firing,

were the surviving police. On the naked rock there was no hope for them. Before

they could clamber down Koolau could have picked off the last man. But he did

not fire, and, after a conference, one of them took off a white undershirt and

waved it as a flag. Followed by another, he advanced along the knife-edge to

their wounded comrade. Koolau gave not sign, but watched them slowly withdraw

and become specks as they descended into the lower valley.

Two hours later, from another thicket, Koolau

watched a body of police trying to make the ascent from the opposite side of

the valley. He saw the wild goats flee before them as they climbed higher and

higher, until he doubted his judgment and sent for Kiloliana who crawled in

beside him.

"No, there is no way," said

Kiloliana.

"The goats?" Koolau questioned.

"They come from over the next valley, but

they cannot pass to this. There is no way. Those men are not wiser than goats.

They may fall to their deaths. Let us watch."

"They are brave men," said Koolau. Let us watch."

Side by side, they lay among the morning-glories,

with the yellow blossoms of the hau dropping upon them from overhead,

watching the motes of men toil upward, till the thing happened, and three of

them, slipping, rolling, sliding, dashed over a cliff-lip and fell sheer half a

thousand feet.

Kiloliana chuckled.

"We will be bothered no more," he

said.

"They have war-guns," Koolau made

answer. "The soldiers have not yet spoken."

In the drowsy afternoon, most of the lepers lay

in their rock dent asleep. Koolau, his rifle on his knees, fresh-cleaned and

ready, dozed in the entrance to his own den. The maid with the twisted arm lay

below in the thicket and kept watch on the knife-edge passage. Suddenly Koolau

was startled wide awake by the sound of an explosion on the beach. The next

instant the atmosphere was incredibly rent asunder. The terrible sound

frightened him. It was as if all the gods had caught the envelope of the sky in

their hands and were ripping it apart as a woman rips apart a sheet of cotton

cloth. But it was such an immense ripping, growing swiftly nearer. Koolau

glanced up apprehensively, as if expecting to see the thing. Then high up on

the cliff overhead the shell burst in a fountain of black smoke. The rock was

shattered, the fragments falling to the foot of the cliff.

Koolau passed his hand across his sweaty brow. He

was terribly shaken. He had no experience with shell-fire, and this was more

dreadful than any thing he had imagined.

"One," said Kapahei, suddenly

bethinking himself to keep count.

A second and third shell flew screaming over the

top of the wall, bursting beyond view. Kapahei methodically kept the count. The

lepers crowded into the open space before the caves. At first they were

frightened, but as the shells continued their flight over head the leper folk

became reassured and began to admire the spectacle. The two idiots shrieked

with delight, prancing wild antics as each air-tormenting shell went by. Koolau

began to recover his confidence. No damage was being done. Evidently they could

not aim such large missiles at such long range with the precision of a

rifle.

But a change came over the situation. The shells

began to fall short. One burst below in the thicket by the knife-edge. Koolau

remembered the maid who lay there on watch, and ran down to see. The smoke was

still rising from the bushes when he crawled in. He was astounded. The branches

were splintered and broken. Where the girl had lain was a hole in the ground.

The girl herself was in shattered fragments. The shell had burst right on

her.

First peering out to make sure no soldiers were

attempting the passage, Koolau started back on the run for the caves. All the

time the shells were moaning, whining, screaming by, and the valley was

rumbling and reverberating with the explosions. As he came in sight of the

caves, he saw the two idiots, cavorting about, clutching each other's hands

with their stumps of fingers. Even as he ran, Koolau saw a spout of black smoke

rise from the ground, near to the idiots. They were flung apart bodily by the

explosion. One lay motionless, but the other was dragging himself by his hands

toward the cave. His legs trailed out helplessly behind him, while the blood

was pouring from his body. He seemed bathed in blood, and as he crawled he

cried like a little dog. The rest of the lepers, with the exception of Kapahei,

had fled into the caves.

"Seventeen," said Kapahei.

"Eighteen," he added.

This last shell had fairly entered into one of

the caves. The explosion caused all the caves to empty. But from the particular

cave no one emerged. Koolau crept in through the pungent, acrid smoke. Four

bodies, frightfully mangled, lay about. One of them was the sightless woman

whose tears till now had never ceased.

Outside, Koolau found his people in a panic and

already beginning to climb the goat-trail that led out of the gorge and on

among the jumbled heights and chasms. The wounded idiot, whining feebly and

dragging himself along on the ground by his hands, was trying to follow. But at

the first pitch of the wall his helplessness overcame him and he fell back.

"It would be better to kill him," said

Koolau to Kapahei, who still sat in the same place.

"Twenty-two," Kapahei answered.

"Yes, it would be a wise thing to kill him.

Twenty-three—twenty-four."

The idiot whined sharply when he saw the rifle

leveled at him. Koolau hesitated, then lowered the gun.

"It is a hard thing to do," he

said.

"You are a fool, twenty-six,

twenty-seven," said Kapahei. "Let me show you."

He arose and, with a heavy fragment of rock in

his hand, approached the wounded thing. As he lifted his arm to strike, a shell

burst full upon him, relieving him of the necessity of the act and at the same

time putting an end to his count.

Koolau was alone in the gorge. He watched the

last of his people drag their crippled bodies over the brow of the height and

disappear. Then he turned and went down to the thicket where the maid had been

killed. The shell-fire still continued, but he remained; for far below he could

see the soldiers climbing up. A shell burst twenty feet away. Flattening

himself into the earth, he heard the rush of the fragments above his body. A

shower of hau blossoms rained upon him. He lifted his head to peer down

the trail, and sighed. He was very much afraid. Bullets from rifles would not

have worried him, but this shell-fire was abominable. Each time a shell

shrieked by, he shivered and crouched; but each time he lifted his head again

to watch the trail.

At last the shells ceased. This, he reasoned, was

because the soldiers were drawing near. They crept along the trail in single

file, and he tried to count them until he lost track. At any rate, there were a

hundred or so of them—all come after Koolau the leper. He felt a fleeting

prod of pride. With war-guns and rifles, police and soldiers, they came for

him, and he was only one man, a crippled wreck of a man at that. They offered a

thousand dollars for him, dead or alive. In all his life he had never possessed

that much money. The thought was a bitter one. Kapahei had been right. He,

Koolau, had done no wrong. Because the haoles wanted labor with which to

work the stolen land, they had brought in the Chinese coolies, and with them

had come the sickness. And now, because he had caught the sickness, he was

worth a thousand dollars—but not to himself. It was his worthless

carcass, rotten with disease or dead from a bursting shell, that was worth all

that money.

When the soldiers reached the knife-edged

passage, he was prompted to warn them. But his gaze fell upon the body of the

murdered maid, and he kept silent. When six had ventured on the knife-edge, he

opened fire. Nor did he cease when the knife-edge was bare. He emptied his

magazine, reloaded, and emptied it again. He kept on shooting. All his wrongs

were blazing in his brain, and he was in a fury of vengeance. All down the

goat-trail the soldiers were firing, and though they lay flat and sought to

shelter themselves in the shallow inequalities of the surface, they were

exposed marks to him. Bullets whistled and thudded about him, and an occasional

ricochet sang sharply through the air. One bullet plowed a crease through his

scalp, and a second burned across his shoulder-blade without breaking the

skin.

It was a massacre, in which one man did the

killing. The soldiers began to retreat, helping along their wounded. As Koolau

picked them off he became aware of the smell of burnt meat. He glanced about

him at first, and then discovered that it was his own hands. The heat of the

rifle was doing it. The leprosy had destroyed most of the nerves in his hands.

Though his flesh burned and he smelled it, there was no sensation.

He lay in the thicket, smiling, until he

remembered the war-guns. Without doubt they would open up on him again, and

this time upon the very thicket from which he had inflicted the damage.

Scarcely had he changed his position to a nook behind a small shoulder of the

wall where he had noted that no shells fell, than the bombardment recommenced.

He counted the shells. Sixty more were thrown into the gorge before the

war-guns ceased. The tiny area was pitted with their explosions, until it

seemed impossible that any creature could have survived. So the soldiers

thought, for, under the burning afternoon sun, they climbed the goat-trail

again. And again the knife-edge passage was disputed, and again they fell back

to the beach.

For two days longer Koolau held the passage,

though the soldiers contented themselves with flinging shells into his retreat.

Then Pahau, a leper boy, come to the top of the wall at the back of the gorge

and shouted down to him that Kiloliana, hunting goats that they might eat, had

been killed by a fall, and that the women were frightened and knew not what to

do. Koolau called the boy down and left him with a spare gun with which to

guard the passage. Koolau found his people disheartened. The majority of them

were too helpless to forage food for themselves under such forbidding

circumstances, and all were starving. He selected two women and a man who were

not too far gone with the disease, and sent them back to the gorge to bring up

food and mats. The rest he cheered and consoled until even the weakest took a

hand in building rough shelters for themselves.

But those he had dispatched for food did not

return, and he started back for the gorge. As he came out on the brow of the

wall, half a dozen rifles cracked. A bullet tore through the fleshy part of his

shoulder, and his cheek was cut by a sliver of rock where a second bullet

smashed against the cliff. In the moment that this happened, and as he leaped

back, he saw that the gorge was alive with soldiers. His own people had

betrayed him. The shell-fire had been too terrible, and they had preferred the

prison of Molokai.

Koolau dropped back and unslung one of his heavy

cartridge-belts. Lying among the rocks, he allowed the head and shoulders of

the first soldier to rise clearly into view before pulling the trigger. Twice

this happened, and then, after some delay, in place of a head and shoulders a

white flag was thrust above the edge of the wall.

"What do you want?" he demanded.

"I want you, if you are Koolau the

leper," came the answer.

Koolau forgot where he was, forgot everything, as

he lay and marveled at the strange persistence of these haoles who would

have their will though the sky fell in. Ay, the would have their will over all

men and all things, even though they died in getting it. He could not but

admire them, too, what of that will in them that was stronger than life and

that bent all things to their bidding. He was convinced of the hopelessness of

his struggle. There was no gainsaying that terrible will of the haoles.

Though he had killed a thousand, yet would they rise like the sands of the sea

and come upon him, ever more and more. They never knew when they were beaten.

That was their fault and their virtue. It was where his own kind lacked. He

could see, now, how the handful of the preachers of God and the preachers of

Rum had conquered the land. It was because—

"Well, what have you got to

say?"Will you come with me?"

It was the voice of the invisible man under the

white flag. There he was, like any haole, driving straight toward the

end determined.

"Let us talk," said Koolau.

The man's head and shoulders arose, then his hole

body. He was a smooth-faced, blue-eyed youngster of twenty-five, slender and

natty in his captain's uniform. He advanced until halted, then seated himself a

dozen feet away:

"You are a brave man," said Koolau

wonderingly. "I could kill you like a fly."

"No you could n't," was the

answer.

"Why not?"

"Because you are a man, Koolau, though a bad

one. I know your story. You kill fairly."

Koolau grunted, but was secretly pleased.

"What have you done with my people?" he

demanded. "The boy, the two women, and the man?"

"They gave themselves up, as I have now come

for you to do."

Koolau laughed incredulously.

"I am a free man," he announced.

"I have done no wrong. All I ask is to be left alone. I have lived free,

and I shall die free. I will never give myself up."

"Then your people are wiser than you,"

answered the young captain. "Look—they are coming now."

Koolau turned and watched the remnant of his band

approach. Groaning and sighing, a ghastly procession, it dragged its

wretchedness past. It was given to Koolau to taste a deeper bitterness, for

they hurled imprecations and insults at him as they went by; and the panting

hag who brought up the rear, halted, and, with skinny, harpy-claws extended,

shaking her snarling death's head from side to side, she laid a curse upon him.

One by one they dropped over the lip-edge and surrendered to the hiding

soldiers.

"You can go now," said Koolau to the

captain. "I will never give myself up. That is my last word.

Goodbye."

The captain slipped over the cliff to his

soldiers. The next moment, and without a flag of truce, he hoisted his hat on

his scabbard, and Koolau's bullet tore through it. That afternoon they shelled

him out from the beach, and as he retreated into the high inaccessible pockets

beyond, the soldiers followed him.

For six weeks they hunted him from pocket to

pocket, over the volcanic peaks and along the goat-trails. When he hid in the

Lantana jungle, they formed lines of beaters, and through Lantana jungle and

guava scrub they drove him like a rabbit. But ever he turned and doubled and

eluded. There was no cornering him. When pressed too closely, his sure rifle

held them back and they carried their wounded down the goat-trails to the

beach. There were times when they did the shooting as his brown body showed for

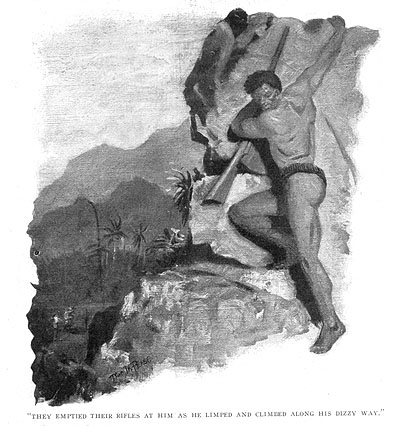

a moment through the underbrush. Once, five of them caught him on an exposed

goat-trail between pockets. They emptied their rifles at him as he limped and

climbed along his dizzy way. Afterward they found blood-stains and knew that he

was wounded. At the end of six weeks they gave up. The soldiers and police

returned to Honolulu, and Kalalau Valley was left to him for his own, though

head-hunters ventured after him from time to time and to their own undoing.

Two years later, and for the last time, Koolau

crawled into a thicket and lay down among the ti-leaves and wild-ginger

blossoms. Free he had lived, and free he was dying. A slight drizzle of rain

began to fall, and he drew a ragged blanket about the distorted wreck of his

limbs. His body was covered with an oilskin coat. Across his chest he laid his

Mauser rifle, lingering affectionately for a moment to wipe the dampness from

the barrel. The hand with which he wiped had no fingers left upon it with which

to pull the trigger.

He closed his eyes, for, from the weakness in his

body and the fuzzy turmoil in his brain, he knew that his end was near. Like a

wild animal he had crept into hiding to die. Half-conscious, aimless and

wandering, he lived back in his life to his early manhood on Niihau. As life

faded and the drip of the rain grew dim in his ears, it seemed to him that he

was once more in the thick of the horse-breaking, with raw colts rearing and

bucking under him, his stirrups tied together beneath, or charging madly about

the breaking-corral and driving the helping cowboys over the rails. The next

instant, and with seeming naturalness, he found himself pursuing the wild bulls

of the upland pastures, roping them and leading them down to the valleys. Again

the sweat and dust of the branding pen stung his eyes and bit his nostrils.

All his lusty, whole-bodied youth was his, until

the sharp pangs of impending dissolution brought him back. He lifted his

monstrous hands and gazed at them in wonder. But how? Why? Why should the

wholeness of that wild youth of his change to this? Then he remembered, and

once again, and for a moment, he was Koolau, the leper. His eyelids fluttered

wearily down and the drip of the rain ceased in his ears. A prolonged trembling

set up in his body. This, too, ceased. He half-lifted his head, but it fell

back. Then his eyes opened, and did not close. His last thought was of his

Mauser, and he pressed it against his chest with his folded, fingerless hands.

So passed Koolau, the leper.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.