Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

KEESH, THE SON OF KEESH

BY JACK LONDON

Author of "The God of His Fathers," and "Son of the Wolf."

![]() HUS will I give six blankets, warm and double; six files,

large and hard; six Hudson Bay knives, keen-edged and long; two canoes,

the work of Mogum, the Maker of Things; ten dogs, heavy-shouldered and

strong in the harness, and three guns—the trigger of one be

broken, but it is a good gun and can doubtless be fixed."

HUS will I give six blankets, warm and double; six files,

large and hard; six Hudson Bay knives, keen-edged and long; two canoes,

the work of Mogum, the Maker of Things; ten dogs, heavy-shouldered and

strong in the harness, and three guns—the trigger of one be

broken, but it is a good gun and can doubtless be fixed."

Keesh paused and swept his eyes over the circle

of intent faces. It

was the time of the Great Fishing, and he was bidding to Gnob for Su-Su,

his daughter. The place was the St. George Mission by the Yukon, and the

tribes had gathered for many a hundred miles. From north, south, east

and west they had come, even from Tozikakat and far Tana-naw.

"And further, O Gnob, thou art chief of the

Tana-naw, and I, Keesh,

the son of Keesh, I am chief of the Thlunget. Wherefore, when my seed

springs from the loins of thy daughter there shall be a friendship

between the tribes, a great friendship and Tana-naw and Thlunget shall

be brothers of the blood in the time to come. That which I have said I

will do, that will I do. And how is it with you, O Gnob, in this

matter?"

Gnob nodded his head gravely, his gnarled and

age-twisted face

inscrutably masking the soul that dwelt behind. His narrow eyes burned

like twin coals through their narrow slits, as he piped in a high,

cracked voice. "But that is not all."

"What more?" Keesh demanded. "Have

I not offered full measure? Was

there ever yet a Tana-naw maiden who fetched so great a price? Then name

her!"

An open snicker passed round the circle, and

Keesh knew that he stood

in shame before these people.

"Nay, nay, good Keesh, thou dost not

understand." Gnob made a soft,

stroking gesture. "The price is fair. It is a good price. Nor do I

question the broken trigger. But that is not all. What of the man?"

"Ah, what of the man?" the circle

snarled.

"It is said," Gnob's shrill voice

piped, "it is said that Keesh does

not walk in the way of his fathers. It is said that he has wandered into

the dark, after strange gods, and that he is become afraid."

The face of Keesh went dark. "It is a

lie!" he thundered. "Keesh is

afraid of no man!"

"It is said," old Gnob piped on,

"that he has hearkened to the speech

of the white man up at the Big House, and that he bends head to the

white man's god, and, moreover, that blood is displeasing to the white

man's god."

Keesh dropped his eyes, and his hands clenched

passionately. The

savage circle laughed derisively, and in the ear of Gnob whispered

Madwan the Shaman, high priest of the tribe and maker of medicine.

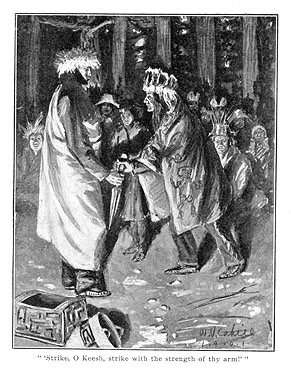

The Shaman poked among the shadows on the rim of

the firelight and

roused up a slender young boy, whom he brought face to face with Keesh,

and in the hand of Keesh he thrust a knife.

Gnob leaned forward. "Keesh! O Keesh! Darest

thou to kill a man?

Behold! This be Kitz-noo, a slave. Strike, O Keesh, strike with the

strength of thy arm!"

The boy trembled and waited the stroke. Keesh

looked at him and

thoughts of Mr. Brown's higher morality floated through his mind, and

strong upon him was a vision of the leaping flames of Mr. Brown's

particular brand of hell-fire. The knife fell to the ground, and the boy

sighed and went out beyond the firelight with shaking knees. At the feet

of Gnob sprawled a wolf dog, which bared its gleaming teeth and prepared

to spring after the boy. But the Shaman ground his foot into the brute's

body, and so doing, gave Gnob an idea.

"And then, O Keesh, what wouldst thou do,

should a man do this thing

to you?" And as he spoke, Gnob held a ribbon of salmon to White Fang,

and when the animal attempted to take it, smote him sharply on the nose

with a stick. "And afterward, O Keesh, wouldst thou do thus?" White

Fang

was cringing back on his belly and fawning to the hand of Gnob.

"Listen!"—leaning on the arm of

Madwan, Gnob had risen to his

feet—"I am very old, and because I am very old I will tell thee

things. Thy father, Keesh, was a mighty man. And he did love the song of

the bow-string in battle, and these eyes have beheld him cast a spear

till the head stood out beyond a man's body. But thou art unlike. Since

thou left the Raven to worship the Wolf, thou art become afraid of

blood, and thou makest thy people afraid. This is not good. For behold,

when I was a boy, even as Kitz-noo there. There was no white man in all

the land. But they came, one by one, these white men, till now they are

many. And they are a restless breed, never content to rest by the fire

with a full belly and let the morrow bring its own meat. A curse was

laid upon them, it would seem, and they must work it out in toil and

hardship."

Keesh was startled. A recollection of a hazy

story told by Mr. Brown

of one Adam, of old time, came to him, and it seemed that Mr. Brown had

spoken true.

"So they lay hands upon all they behold,

these white men, and they go

everywhere and behold all things. And ever do more follow in their

steps, so that if nothing be done they will come to possess all the land

and there will be no room for the tribes of the Raven. Wherefore it is

meet that we fight with them till none is left. Then will we hold the

passes and the land, and perhaps our children and our children's

children shall flourish and grow fat. There is a great struggle to come,

when Wolf and Raven shall grapple; but Keesh will not fight, nor will he

let his people fight. So it is not well that he should take to him my

daughter. Thus have I spoken, I Gnob, chief of the Tana-naw."

"But the white men are good and great,"

Keesh made answer. "The white

men have taught us many things. The white men have given us blankets and

knives and guns, such as we have never made and never could make. I

remember in what manner we lived before they came. I was unborn then,

but I have it from my father. When we went on the hunt we must creep so

close to the moose that a spear cast would cover the distance. To-day we

use the white man's rifle, and farther away than can a child's cry be

heard. We ate fish and meat and berries—there was nothing else to

eat—and we ate without salt. How many be there among you who care

to go back to the fish and meat without salt?"

It would have sunk home had not Madwan leaped to

his feet ere silence

could come. "And first a question to thee, Keesh. The white man up at

the Big House tells you that it is wrong to kill. Yet do we not know

that the white men kill? Have we forgotten the great fight on the

Koyokuk? Or the great fight at the Nuklukyeto, where three white men

killed twenty of the Tozikakats? Do you think we no longer remember the

three men of the Tana-naw that the white man Macklewrath killed? Tell

me, O Keesh, why does the Shaman Brown teach you that it is wrong to

fight, when all his brothers fight?"

"Nay, nay, there is no need to answer,"

Gnob piped, while Keesh

struggled with the paradox. "It is very simple. The Good Man Brown would

hold the Raven tight whilst his brothers pluck the feathers." He raised

his voice. "But so long as there is one Tana-naw to strike a blow, or

one maiden to bear a man-child, the Raven shall not be plucked!"

Gnob turned to a husky young man across the fire.

"And what sayest

thou, Makamuk, who art brother of Su-Su?"

Makamuk came to his feet. A long face-scar lifted

his upper lip into

a perpetual grin, which belied the glowering ferocity of his eyes. "This

day," he began, with cunning irrelevance, "I came by the Trader

Macklewrath's cabin. And in the door I saw a child laughing at the sun.

And the child looked at me with the Trader Macklewrath's eyes, and it

was frightened. But the mother ran to it and quieted it. The mother was

Ziska, the Thlunget woman."

A snarl of rage rose up and drowned his voice,

which he stilled by

turning dramatically upon Keesh with outstretched arm and accusing

finger.

"So? You give your women away, you Thlunget,

and come to the Tana-naw

for more? But we have need of our women, Keesh, for we must breed men,

many men, against the day when the Raven grapples with the Wolf."

Through the storm of applause Gnob's voice

shrilled clear: "And thou,

Nossabok, who are her favorite brother?"

The young fellow was slender and graceful, with

the strong aquiline

nose and high brows of his type; but from some nervous affliction the

lid of one eye drooped at odd times in a suggestive wink. Even as he

arose it so drooped and rested a moment against his cheek. But it was

not greeted with the accustomed laughter. Every face was grave. "I, too,

passed by the Trader Macklewrath's cabin," he rippled in soft, girlish

tones, wherein there was much of youth and much of his sister. "And I

saw Indians, with the sweat running into their eyes and their knees

shaking with weariness—I say, I saw Indians groaning under the

logs for the store which the Trader Macklewrath is to build. And with my

eyes I saw them chipping wood to keep the Shaman Brown's big house warm

through the frost of the long nights. This be squaw work. Never shall

the Tana-naw do the like. We shall be blood brothers to men, not squaws;

and the Thlunget be squaws."

A deep silence fell, and all eyes centered on

Keesh. He looked about

him carefully, deliberately, full into the face of each grown man.

"So," he said, passionlessly. "And

so," he repeated. Then turned upon

his heel without further word and passed out into the darkness.

Wading among sprawling babies and bristling

wolf-dogs, he threaded

the great camp, and on its outskirts came upon a woman at work by the

light of a fire. With strings of bark he stripped from the long roots of

creeping vines, she was braiding rope for the fishing. For some time

without speech, he watched her deft hands bringing law and order out of

the unruly mass of curling fibers. She was good to look upon, swaying

there to her task, strong-limbed, deep-chested, and with hips made for

motherhood. And the bronze of her face was golden in the flickering

light, her hair blue-black, her eyes jet.

"O Su-Su," he spoke finally, "thou

has looked upon me kindly in the

days that have gone, and in the days yet young——"

"O Su-Su," he spoke finally, "thou

has looked upon me kindly in the

days that have gone, and in the days yet young——"

"I looked kindly upon thee for that thou

wert chief of the Thlunget,"

she answered quickly, "and because thou wert big and strong."

"Ay——"

"But that was in the old days of the

fishing," she hastened to add,

"before the Shaman Brown came and taught thee ill things and led thy

feet."

"But I would tell

the——"

She held one hand in a gesture which reminded him

of her father.

"Nay, I know already the speech that stirs in thy throat, O Keesh, and I

make answer now. It so happens that the fish of the water and the beasts

of the forest bring forth after their kind. And this is good. Likewise

it happens to women. It is for them to bring forth their kind, and even

the maiden, while she is yet a maiden, feels the pang of the birth, and

the pain of the breast, and the small hands at the neck. And when such

feeling is strong, then does each maiden look about her with secret eyes

for the man—for the man who shall be fit to father her kind. So

have I felt. So did I feel when I looked upon thee and found thee big

and strong, a hunter and fighter of beasts and men, well able to win

meat when I should eat for two, well able to keep danger afar off when

my helplessness drew nigh. But that was before the day the Shaman Brown

came into the land and taught thee——"

"But it is not right, Su-Su. I have it on

good

word——"

"It is not right to kill. I know what thou

wouldst say. Then breed

thou after thy kind, the kind that does not kill; but come not on such

quest among the Tana-naw. For it is said, in the time to come that the

Raven shall grapple with the Wolf. I do not know, for this be the affair

of men; but I do know that it is for me to bring forth men against that

time."

"Su-Su," Keesh broke in; "thou

must hear me——"

"A man would beat me with a stick and

make me hear," she

sneered. "But thou . . . here!" She thrust a bunch of bark into his

hand. "I cannot give thee my self, but this, yes. It looks fittest in

thy hands. It is squaw work, so braid away."

He flung it from him, the angry blood pounding a

muddy path under his

bronze.

"One thing more," she went on.

"There be an old custom which thy

father and mine were not strangers to. When a man fell in battle his

scalp is carried away in token. Very good. But thou, who have foresworn

the Raven, must do more. Thou must bring me, not scalps, but heads, two

heads, and then will I give thee, not bark, but a brave-beaded belt, and

sheath, and long Russian knife. Then will I look kindly upon thee once

again and all will be well."

"So," the man pondered. "So."

Then he turned away and passed out

through the light.

"Nay, O Keesh!" she called after him.

"Not two heads, but three at

least!"

But Keesh remained true to his conversion, lived

uprightly and made

his tribe people obey the gospel as propounded by the Reverend Jackson

Brown. Through all the time of the fishing he gave no heed to the Tana-naw,

nor took notice of the sly things which were said, or the laughter

of the women of the many tribes. After the fishing Gnob and his people,

with great store of salmon, sun-dried and smoke-cured, departed for the

hunting on the head reaches of the Tana-naw. Keesh watched them go, but

did not fail in his attendance at mission service, where he prayed

regularly and led the singing with his deep bass voice.

The Reverend Jackson brown delighted in that deep

bass voice, and

because of his sterling qualities deemed him the most promising convert.

Macklewrath doubted this. He did not believe in the efficacy of the

conversion of the heathen, and he was not slow in speaking his mind. But

Mr. Brown was a large man, in his way, and he argued it out with such

convincingness, all of one long fall night, that the trader, driven from

position after position, finally announced in desperation: "Knock out my

brains with apples, Brown, if I don't become a convert myself—if

Keesh holds fast, true blue, for two years!" Mr. Brown never lost an

opportunity, so he clinched the matter on the spot with a virile hand

grip, and thenceforth the conduct of Keesh was to determine the ultimate

abiding place of Macklewrath's soul.

But there came news one day, after the winter's

rime had settled down

over the land sufficiently for travel. A Tana-naw man arrived at the St.

George Mission in quest of ammunition and bringing information that Su-Su had

set eyes on Nee-Koo, a nervy young hunter who had bid brilliantly

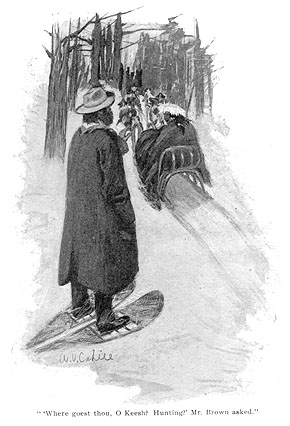

for her by old Gnob's fire. It was at about this time that the Reverend

Jackson Brown came upon Keesh by the wood trail which leads down to the

river. Keesh had his best dogs in the harness, and shoved under the

sled-lashings was his largest and finest pair of snowshoes.

But there came news one day, after the winter's

rime had settled down

over the land sufficiently for travel. A Tana-naw man arrived at the St.

George Mission in quest of ammunition and bringing information that Su-Su had

set eyes on Nee-Koo, a nervy young hunter who had bid brilliantly

for her by old Gnob's fire. It was at about this time that the Reverend

Jackson Brown came upon Keesh by the wood trail which leads down to the

river. Keesh had his best dogs in the harness, and shoved under the

sled-lashings was his largest and finest pair of snowshoes.

"Where goest thou, O Keesh? Hunting?"

Mr. Brown asked, falling into

the Indian manner.

Keesh looked him steadily in the eyes for a full

minute, then started

up his dogs. Then again, turning his deliberate gaze upon the

missionary, he answered, "No; I go to hell."

In an open space, striving to burrow into the

snow as though for

shelter from the appalling desolateness, huddled three dreary lodges.

Ringed all about a dozen paces away, was the somber forest. Overhead

there was no keen blue sky of naked space, but a vague, misty curtain,

pregnant with snow, which had drawn between. There was no wind, no

sound, nothing but the snow and silence. Nor was there even the general

stir of life about the camp; for the hunting party had run upon the

flank of the caribou herd and the kill had been large. Thus after the

period of fasting had come the plentitude of feasting, and thus, in

broad daylight, they slept heavily under their roosts of moosehide.

By a fire, before one of the lodges, five pairs

snowshoes stood on

end in their element, and by the fire sat Su-Su. The hood of her

squirrelskin parka was about her hair and well drawn up around her

throat; but her hands were unmittened and nimbly at work with needle and

sinew, completing the last fantastic design on a belt of leather faced

with bright, scarlet cloth. A dog, somewhere at the rear of one of the

lodges, raised a short, sharp bark, then ceased as abruptly as it had

begun. Once, her father, in the lodge at her back, gurgled and grunted

in his sleep. "Bad dreams," she smiled to herself. "He grows old

and

that last joint was too much."

She placed the last bead, knotted the sinew, and

replenished the

fire. Then, after gazing long into the flames, she lifted her head to

the harsh crunch-crunch of a moccasined foot against the flinty snow

granules. Keesh was at her side, bending slightly forward to a load

which he bore upon his back. This was wrapped loosely in a soft tanned

moosehide, and he dropped it carelessly into the snow and sat down. They

looked at each other long and without speech.

"It is a far fetch, O Keesh," she said

at last; "a far fetch from St.

George Mission by the Yukon."

"Ay," he made answer, absently, his

eyes fixed upon the belt and

taking note of its girth. "But where is the knife?" he demanded.

"Here." She drew it from inside her

parka and flashed its naked

length in the firelight. "It is a good knife."

"Give it to me," he commanded.

"Nay, O Keesh," she laughed. "It

may be that thou was not born to

wear it."

"Give it to me," he reiterated, without

change of tone. "I was so

born."

But her eyes, glancing coquettishly past him to

the moosehide, saw

the snow about it slowly reddening. "It is blood, Keesh?" she

asked.

"Ay, it is blood. But give me the belt and

the long Russian

knife."

She felt suddenly afraid, but thrilled when he

took the belt roughly

from hr, thrilled to the roughness. She looked at him softly, and was

aware of a pain at the breast and of small hands clutching her

throat.

"It was made for a smaller man," he

remarked, grimly, drawing in his

abdomen and clasping the buckle at the first hole.

Su-Su smiled, and her eyes were yet softer. Again

she felt the soft

hands at her throat. He was good to look upon, and the belt was indeed

small, made for a smaller man; but what did it matter? She could make

many belts.

Su-Su smiled, and her eyes were yet softer. Again

she felt the soft

hands at her throat. He was good to look upon, and the belt was indeed

small, made for a smaller man; but what did it matter? She could make

many belts.

"But the blood?" she asked, urged on my

a hope new-born and growing.

"The blood, Keesh? Is it . . . are they . . . heads?"

"Ay."

"They must be very fresh, else would the

blood be frozen."

"Ay; it is not cold, and they be fresh,

quite fresh."

"Oh, Keesh!" Her face was warm and

bright. "And for me?"

"Ay; for thee."

He took hold of a corner of the hide, flirted it

open, and rolled the

heads out before her.

"Three," he whispered, savagely;

"nay, four at least."

But she sat transfixed. There they lay—the

soft-featured Nee-Koo; the gnarled old face of Gnob; Makamuk, grinning at her

with his

lifted upper lip; and lastly, Nossabok, his eyelid, up to its old

trick, drooped on his girlish cheek in a suggestive wink. There they

lay, the firelight flashing upon and playing over them, and from each of

them a widening circle dyed the snow to scarlet.

Once, in the forest, an over-burdened pine

dropped its load of snow,

and the echoes reverberated hollowly down the gorge; but neither

stirred. The short day had been waning fast, and darkness was wrapping

round the camp when White Fang trotted up toward the fire. He paused to

reconnoiter, but not being driven back, came closer. His nose shot

swiftly to the side, nostrils a-tremble and bristles rising along the

spine, and straight and true he followed the sudden scent of his

master's head. He sniffed it gingerly at first, and licked the forehead.

Then he sat abruptly down, pointed his nose up at the first faint star,

and raised the long wolf howl.

This brought Su-Su to herself. She glanced across

at Keesh, who had

unsheathed the Russian knife and was watching her intently. His face was

firm and set, and in it she read the law. Slipping back the hood of her

parka, she bared her neck and rose to her feet. There she paused and

took a long look about her, at the rimming forest, at the faint stars in

the sky, at the camp, at the snowshoes in the snow—a last long,

comprehensive look at life. A light breeze stirred her hair from the

side, and for the space of deep breath she turned her head and followed

it around until she met it full-faced.

Then she walked over to Keesh and said: "I

am ready."

From the January, 1902 issue of Ainslee's Magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.