Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

HOUSEKEEPING IN THE KLONDIKE

BY JACK LONDON

ILLUSTRATED BY E. W. DEMING

OUSEKEEPING in the Klondike - that's bad! And by men -

worse. Reverse the propositions, if you will, yet you will fail to mitigate,

even by a hair's-breadth, the woe of it. It is bad, for a man to keep house,

and it is equally bad to keep house in the Klondike. That's the sum and

substance of it. Of course men will be men, and especially is this true of the

kind who wander off to the frozen rim of the world. The glitter of gold is in

their eyes, they are borne along by uplifting ambition, and in their hearts is

a great disdain for everything in the culinary department save

"grub." "Just so long as it's grub," they say, coming in

off trail, gaunt and ravenous, "grub, and piping hot." Nor do they

manifest the slightest regard for the genesis of the same; they prefer to

begin at "revelations."

OUSEKEEPING in the Klondike - that's bad! And by men -

worse. Reverse the propositions, if you will, yet you will fail to mitigate,

even by a hair's-breadth, the woe of it. It is bad, for a man to keep house,

and it is equally bad to keep house in the Klondike. That's the sum and

substance of it. Of course men will be men, and especially is this true of the

kind who wander off to the frozen rim of the world. The glitter of gold is in

their eyes, they are borne along by uplifting ambition, and in their hearts is

a great disdain for everything in the culinary department save

"grub." "Just so long as it's grub," they say, coming in

off trail, gaunt and ravenous, "grub, and piping hot." Nor do they

manifest the slightest regard for the genesis of the same; they prefer to

begin at "revelations."

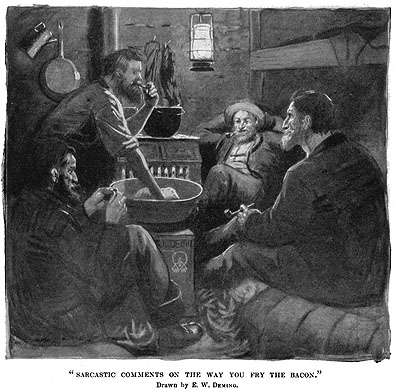

Yes, it would seem a pleasant task to cook for

such men; but just let them lie around cabin to rest up for a week, and see

with what celerity they grow high-stomached and make sarcastic comments on the

way you fry the bacon or boil the coffee. And behold how each will spring his

own strange and marvelous theory as to how sour-dough bread should be mixed and

baked. Each has his own recipe (formulated, mark you, from personal experience

only), and to him it is an idol of brass, like unto no other man's, and he'll

fight for it - ay,. down to the last wee pinch of soda - and if

need be, die for it. If you should happen to catch him on trail, completely

exhausted, you may blacken his character, his flag, and his ancestral tree with

impunity; but breathe the slightest whisper against his sour-dough bread, and

he will turn upon and rend you.

From this is may be gathered what an unstable

thing sour dough is. Never was coquette so fickle. You cannot depend upon it.

Still, it is the simplest thing in the world. Make a batter and place it near

the stove (that it may not freeze) till it ferments or sours. Then mix the

dough with it, and sweeten with soda to taste - of course replenishing the

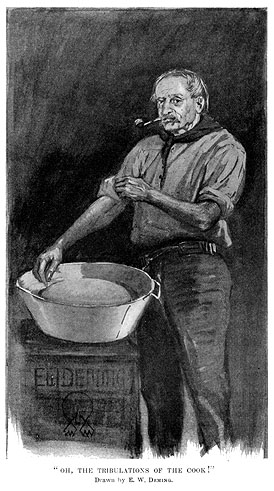

batter for next time. There it is. Was there ever anything simpler? But, oh,

the tribulations of the cook! It is never twice the same. If the batter could

only be placed away in an equable temperature, all well and good. If one's

comrades did not interfere, much vexation of spirit might be avoided. But this

cannot be; for Tom fires up the stove till the cabin is become like the

hot-room of a Turkish bath; Dick forgets all about the fire till the place is

a refrigerator; then along comes Harry and shoves the sour-dough bucket right

against the stove to make way for the drying of this mittens. Now heat is a

most potent factor in accelerating the fermentation of flour and water, and

hence the unfortunate cook is constantly in disgrace with Tom, Dick, and Harry.

Last week his bread was yellow from a plethora of soda; this week it is sour

from a prudent lack of the same; and next week - ah, who can tell save the god

of the fire-box?

Some cooks aver that they have so cultivated

their olfactory organs that they can tell to the fraction of a degree just how

sour the batter is. Nevertheless they have never been known to bake two batches

of bread which were at all alike. But this fact casts not the slightest shadow

upon the infallibility of their theory. One and all, they take advantage of

circumstances, and meanly crawl out by laying the blame upon the soda, which

was dampened "the time the canoe overturned," or upon the flour,

which they got in trade from "that half-breed fellow with the

dogs."

The pride of the Klondike cook in his bread is

something which passes understanding. The highest commendatory degree which can

be passed upon a man in that country, and the one which distinguishes him from

the tenderfoot, is that of being a "sour-dough boy." Never was a

college graduate prouder of his "sheepskin" than the old-timer of

this appellation. There is a certain distinction about it, from which the

new-comer is invidiously excluded. A tenderfoot with his baking-powder is an

inferior creature, a freshman; but a "sour-dough boy" is a man of

stability, a post-graduate in that art of arts - bread-making.

Next to bread a Klondike cook strives to achieve

distinction by his doughnuts.

This may appear frivolous at first glance, and at

second, considering the materials with which he works, an impossible feat. But

doughnuts are all-important to the man who goes on a trail for a journey of any

length. Bread freezes easily, and there is less grease and sugar, and hence

less heat in it, than in doughnuts. The latter do not solidify except at

extremely low temperatures, and they are very handy to carry in the pockets of

a Mackinaw jacket and munch as one travels along. They are made much after the

manner of their brethren in warmer climes, with the exception that they are

cooked in bacon grease - the more grease, the better they are. Sugar is the

cook's chief stumbling-block; if it is very scarce, why, add more grease. The

men never mind - on trail. In the cabin? - well, that's another matter;

besides, bread is good enough for them then.

This may appear frivolous at first glance, and at

second, considering the materials with which he works, an impossible feat. But

doughnuts are all-important to the man who goes on a trail for a journey of any

length. Bread freezes easily, and there is less grease and sugar, and hence

less heat in it, than in doughnuts. The latter do not solidify except at

extremely low temperatures, and they are very handy to carry in the pockets of

a Mackinaw jacket and munch as one travels along. They are made much after the

manner of their brethren in warmer climes, with the exception that they are

cooked in bacon grease - the more grease, the better they are. Sugar is the

cook's chief stumbling-block; if it is very scarce, why, add more grease. The

men never mind - on trail. In the cabin? - well, that's another matter;

besides, bread is good enough for them then.

The cold, the silence, and the darkness somehow

seem to be considered the chief woes of the Klondiker. But this is all wrong.

There is one woe which overshadows all others - the lack of sugar. Every party

which goes north signifies a manly intention to do without sugar, and after it

gets there bemoans itself upon its lack of foresight. Man can endure hardship

and horror with equanimity, but take from him his sugar, and he raises his

lamentations to the stars. And the worst of it is that it all falls back upon

the long-suffering cook. Naturally, coffee, and mush, and dried fruit, and

rice, eaten without sugar, do not taste exactly as they should. A certain

appeal to the palate is missing. Then the cook is blamed for his vile

concoctions. Yet, if he be a man of wisdom, he may judiciously escape the major

part of this injustice. When he places a pot of mush upon the table, let him

see to it that it is accompanied by a pot of stewed dried apples or peaches.

This propinquity will suggest the combination to the men, and the flatness of

the one will be neutralized by the sharpness of the other. In the distress of a

sugar famine, if he be a cook of parts, he will boil rice and fruit together in

one pot; and if he cook a dish of rice and prunes properly, of a verity he will

cheer up the most melancholy member of the party, and extract from him great

gratitude.

Such a cook must indeed be a man of resources.

Should his comrades cry out that vinegar be placed upon the beans, and there is

no vinegar, he must know how to make it out of water, dried apples, and brown

paper. He obtains the last from the bacon-wrappings, and it is usually

saturated with grease. But that does not matter. He will early learn that in

the land of low temperatures it is impossible for bacon grease to spoil

anything. It is to the white man what blubber and seal oil are to the Eskimo.

Soul-winning gravies may be made from it by the addition of water and browned

flour over the fire. Some cooks base far-reaching fame solely upon their gravy,

and their names come to be on the lips of men wherever they forgather at the

feast. When the candles give out, the cook fills a sardine-can with bacon

grease, manufactures a wick out of the carpenter's sail-twine, and behold! the

slush-lamp stands complete. It goes by another and less complimentary name in

the vernacular, and, next to sour-dough bread, is responsible for more men's

souls than any other single cause of degeneracy in the Klondike.

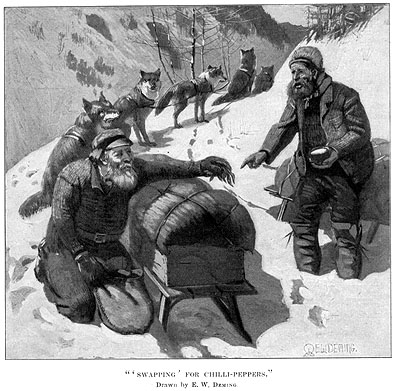

The ideal cook should also possess a Semitic

incline to his soul. Initiative in his art is not the only requisite; he must

keep an eye upon the variety of his larder. He must "swap" grub with

the gentile understandingly; and woe unto him should the balance of trade be

against him. His comrades will thrust it into his teeth every time the bacon is

done over the turn, and they will even rouse him from his sleep to remind him

of it. For instance, previous to the men going out for a trip on trail, he

cooks several gallons of beans in the company of numerous chunks of salt pork

and much bacon grease. This mess he then moulds into blocks of convenient size

and places on the roof, where it freezes into bricks in a couple of hours. Thus

the men, after a weary day's travel, have but to chop off chunks with an axe

and thaw out in the frying-pan. Now the chances preponderate against more than

one party in ten having chilli-peppers in their outfits. But the cook,

supposing him to be fitted for his position, will ferret out that one party,

discover some particular shortage in its grub-supply of which he has plenty,

and swop the same for chill-peppers. These in turn he will incorporate in the

mess aforementioned, and behold a dish which even the hungry arctic gods may

envy. Variety in the grub is a welcome to the men as nuggets. When, after

eating dried peaches for months, the cook trades a few cupfuls of the same for

apricots, the future at once takes on a more roseate hue. Even a change in the

brand of bacon will revivify blasted faith in the country.

It is no sinecure, being cook in the Klondike.

Often he must do his work in a cabin measuring ten by twelve on the inside, and

occupied by three other men besides himself. When it is considered that these

men eat, sleep, lounge, smoke, play cards, and entertain visitors there, and

also in that small space house the bulk of their possessions, the size of the

cook's orbit may be readily computed.

In the morning he sits up in bed, reaches out and strikes the fire, then

proceeds to dress. After that the centre of his orbit is the front of the

stove, the diameter the length of his arms. Even then his comrades are

continually encroaching upon his domain, and he is at constant warfare to

prevent territorial grabs.

In the morning he sits up in bed, reaches out and strikes the fire, then

proceeds to dress. After that the centre of his orbit is the front of the

stove, the diameter the length of his arms. Even then his comrades are

continually encroaching upon his domain, and he is at constant warfare to

prevent territorial grabs.

If the men are working hard on the claim, the

cook is also expected to find his own wood and water. The former he chops up

and sleds into camp, the latter he brings home in a sack - unless he is

unusually diligent, in which case he has a ton or so of water piled up before

the door. Whenever he is not cooking, he is thawing out ice, and between-whiles

running out and hoisting on the windlass for his comrades in the shaft. The

care of dogs also devolves upon him, and he carries his life and a long club in

his hand every time he feeds them.

But there is one thing the cook does not have to

do, nor any man in the Klondike - and that is, make another man's bed. In fact,

the beds are never made except when the blankets become unfolded, or when the

pine needles have all fallen off the boughs which form the mattress. When the

cabin has a dirt floor and the men do their carpenter-work inside, the cook

never sweeps it. It is much warmer to let the chips and shavings remain.

Whenever he kindles a fire he uses a couple of handfuls of the floor. However,

when the deposit becomes so deep that his head is knocking against the roof,

he seizes a shovel and removes a foot or so of it.

Nor does he have any windows to wash; but if the

carpenter is busy he must make his own windows. This is simple. He saws a hole

out of the side of the cabin, inserts a home-made sash, and for panes falls

back upon the treasured writing-tablet. A sheet of this paper, rubbed

thoroughly with bacon grease, becomes transparent, sheds water when it thaws,

and keeps the cold out and the heat in. In cold weather the ice will form upon

the inside of it to the thickness of sometimes two or three inches. When the

bulb of the mercurial thermometer has frozen solid, the cook turns to his

window, and by the thickness of the icy coating infallibly gauges the outer

cold within a couple of degrees.

A certain knowledge of astronomy is required of

the Klondike cook, for another task of his is to keep track of the time. Before

going to bed he wanders outside and studies the heavens. Having located the

Pole Star by means of the Great Bear, he inserts two slender wands in the snow,

a couple of yards apart and in line with the North Star. The next day, when the

sun on the southern horizon casts the shadows of the wands to the northward and

in line, he knows it to be twelve o'clock, noon, and sets his watch and those

of his partners accordingly. As stray dogs are constantly knocking his wands

out of line with the North Star, it becomes his habit to verify them regularly

every night, and thus another burden is laid upon him.

But, after all, while the woes of the man who

keeps house and cooks food in the northland are innumerable, there is one

redeeming feature in his lot which does not fall to the women housewives of

other lands. When things come to a pass with his feminine prototype, she throws

her apron over her head and has a good cry. Not so with him, being a man and a

Klondiker. He merely cooks a little more atrociously, raises a storm of

grumbling, and resigns. After that he takes up his free out-door life again,

and exerts himself mightily in making life miserable for the unlucky comrade

who takes his place in the management of the household destinies.

From the September 15, 1900 issue of Harper's Bazar magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.