Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

"Sacrédam!" the Frenchman said softly, flirting the quick blood from his bitten hand and gazing down on the little puppy choking and gasping in the snow.

Leclère turned to John Hamlin, storekeeper of the Sixty Mile Post. "Dat fo' w'at Ah lak heem. 'Ow moch, eh, you, m'sieu'? 'Ow moch? Ah buy heem, now."

And because he hated him with an exceeding bitter hate, Leclère bought Diable. And for five years the twain adventured across the northland, from St. Michael's and the Yukon Delta to the head-reaches of the Pelly and even so far as the Peace River, Athabasca and the Great Slave. And they acquired a reputation for uncompromising wickedness the like of which never before had attached itself to man and dog.

Diable's father was a great gray timber-wolf. But the mother of Diable, as he dimly remembered her, was a snarling, bickering husky, full-fronted and heavy-chested, with a malign eye, a cat-like grip on life, and a genius for trickery and evil. There was neither faith nor trust in her. Much of evil and much of strength were there in these, Diable's progenitors, and, bone and flesh of their bone and flesh, he had inherited it all. And then came Black Leclère, to lay his heavy hand on the bit of pulsating puppy-life, to press and prod and mold it till it became a big, bristling beast, acute in knavery, overspilling with hate, sinister, malignant, diabolical. With a proper master the puppy might have made a fairly ordinary, efficient sled-dog. He never got the chance. Leclère but confirmed him in his congenital inequity.

The history of Leclère and the dog is a history of war—of five cruel, relentless years, of which their first meeting is fit summary. To begin with, it was Leclère's fault, for he hated with understanding and intelligence, while the long-legged, ungainly puppy hated only blindly, instinctively, without reason or method. At first there were no refinements of cruelty (these were to come later), but simple beatings and crude brutalities. In one of these, Diable had an ear injured. He never regained control of the riven muscles, and ever after the ear drooped limply down to keep keen the memory of his tormentor. And he never forgot.

His puppyhood was a period of foolish rebellion. He was always worsted, but he fought back because it was his nature to fight back. And he was unconquerable. Yelping shrilly from the pain of lash and club, he none the less always contrived to throw in the defiant snarl, the bitter, vindictive menace of his soul, which fetched without fail more blows and beatings. But his was his mother's tenacious grip on life. Nothing could kill him. He flourished under misfortune, grew fat with famine, and out of his terrible struggle for life developed a preternatural intelligence. His was the stealth and cunning of his mother, the fierceness and valor of his wolf sire.

Possibly it was because of his father that he never wailed. His puppy yelps passed with his lanky legs, so that he became grim and taciturn, quick to strike, slow to warn. He answered curse with snarl and blow with snap, grinning the while his implacable hatred; but never again, under the extremest agony, did Leclère bring from him the cry of fear or pain. This unconquerableness only fanned Leclère's wrath and stirred him to greater deviltries. Did Leclère give Diable half a fish and to his mates whole ones, Diable went forth to rob other dogs of their fish. Also he robbed caches and expressed himself in a thousand rogueries till he became a terror to all dogs and the masters of dogs. Did Leclère beat Diable and fondle Babette—Babette, who was not half the worker he was—why, Diable threw her down in the snow and broke her hind leg in his heavy jaws, so that Leclère was forced to shoot her. Likewise, in bloody battles Diable mastered all his team-mates, set them the law of trail and forage, and made them live to the law he set.

In five years he heard but one kind word, received but one soft stroke of a hand, and then he did not know what manner of things they were. He leaped like the untamed thing he was, and his jaws were together in a flash. It was the missionary at Sunrise, a newcomer in the country, who spoke the kind word and gave the soft stroke of the hand. And for six months after, he wrote no letters home to the States, and the surgeon at McQuestion traveled two hundred miles on the ice to save him from blood-poisoning.

Men and dogs looked askance at Diable when he drifted into their camps and posts, and they greeted him with feet threateningly lifted for the kick, or with bristling manes and bared fangs. Once a man did kick Diable, and Diable, with quick wolf-snap, closed his jaws like a steel trap on the man's leg and crunched down to the bone. Whereat the man was determined to have his life, only Black Leclère, with ominous eyes and naked hunting-knife stepped in between. The killing of Diable—ah, sacrédam! that was a pleasure Leclère reserved for himself. Some day it would happen, or else—bah! who was to know? Anyway, the problem would be solved.

For they had become problems to each other, this man and beast, or rather, they had become a problem, the pair of them. The very breaths each drew was a challenge and a menace to the other. Their hate bound them together as love could never bind. Leclère was bent on the coming of the day when Diable should wilt in spirit and cringe and whimper at his feet. And Diable— Leclère knew what was in Diable's mind, and more than once had read it in his eyes. And so clearly had he read that when the dog was at his back he made it a point to glance often over his shoulder.

Men marveled when Leclère refused large money for the dog. "Some day you'll kill him and be out his price," said John Hamlin, once, when Diable lay panting in the snow where Leclère had kicked him and know one knew whether his ribs were broken and no one dared to see.

"Dat," said Leclère dryly, "dat is my biz'ness, m'sieu'."

And the men marveled that Diable did not run away. They did not understand. But Leclère understood. He was a man who had lived much in the open, beyond the sound of human tongue, and he had learned the voices of wind and storm, the sigh of night, the whisper of dawn, the clash of day. In a dim way he could hear the green things growing, the running of the sap, the bursting of the bud. And he knew the subtle speech of the things that moved, of the rabbit in the snare, the moody raven beating the air with hollow wing, the baldface shuffling under the moon, the wolf like a gray shadow gliding betwixt the twilight and the dark. And to him Diable spoke clear and direct. Full well he understood why Diable did not run away, and he looked more often over his shoulder.

When in anger, Diable was not nice to look upon, and more than once had he leaped for Leclère's throat, to be stretched quivering and senseless in the snow by the butt of the very-ready dog-whip. And so Diable learned to bide his time. When he reached his full strength and prime of youth, he thought the time had come. He was broad-chested, powerfully muscled, of far more than ordinary size, and his neck from head to shoulders was a mass of bristling hair—to all appearances a full-blooded wolf. Leclère was lying asleep in his furs when Diable deemed the time to be ripe. He crept upon his stealthily, head low to earth and lone ear laid back, with a feline softness of tread to which even Leclère's delicate tympanum could not responsively vibrate. The dog breathed gently, very gently, and not till he was close at hand did he raise his head. He paused for a moment and looked at the bronzed bull-throat, naked and knotty and swelling to a deep and steady pulse. The slaver dripped down his fangs and slid off his tongue at the sight, and in that moment he remembered his drooping ear, his uncounted blows and wrongs, and without a sound sprang on the sleeping man.

Leclère awoke to the pang of the fangs in his throat, and, perfect animal that he was, he awoke clear-headed and with full comprehension. He closed on the hound's windpipe with both his hands and rolled out of his furs to get his weight uppermost. But the thousands of Diable's ancestors had clung at the throats of unnumbered moose and caribou and dragged them down, and the wisdom of those ancestors was his. When Leclère weight came on top of him, he drove his hind legs upward and in and clawed down chest and abdomen, ripping and tearing through skin and muscle. And when he felt the man's body wince above him and lift, he worried and shook at the man's throat. His team-mates closed around in a snarling, slavering circle, and Diable, with failing breath and fading sense, knew that their jaws were hungry for him. But that did not matter—it was the man, the man above him, and he ripped and clawed and shook and worried to the last ounce of his strength. But Leclère choked him with both his hands till Diable's chest heaved and writhed for the air denied, and his eyes glazed and his jaws slowly loosened and his tongue protruded black and swollen.

"Eh? Bon, you devil!" Leclère gurgled, mouth and throat clogged with his own blood, as he shoved the dizzy dog from him.

And then Leclère cursed the other dogs off as they fell upon Diable. They drew back into a wider circle, squatting alertly on their haunches and licking their chops, each individual hair on every neck bristling and erect.

Diable recovered quickly, and at sound of Leclère voice, tottered to his feet and swayed weakly back and forth.

"A-h-ah! You beeg devil!" Leclère spluttered. "Ah fix you. Ah fix you plentee, by Gar!"

Diable, the air biting into his exhausted lungs like wine, flashed full into the man's face, his jaws missing and coming together with a metallic clip. They rolled over and over on the snow, Leclère striking madly with his fists. Then they separated, face to face, and circled back and forth before each other for an opening. Leclère could have drawn his knife. His rifle was at his feet. But the beast in him was up and raging. He would do the thing with his hands—and his teeth. The dog sprang in, but Leclère knocked him over with a blow of his fist, fell upon him, and buried his teeth to the bone in the dog's shoulder.

It was a primordial setting and a primordial scene, such as might have been in the savage youth of the world. And open space in a dark forest, a ring of grinning wolf-dogs, and in the center two beasts, locked in combat, snapping and snarling, raging wildly about, panting, sobbing, cursing, straining, wild with passion, blind with lust, in a fury of murder, ripping, tearing and clawing in elemental brutishness.

But Leclère caught the dog behind the ear with a blow from his fist, knocking him over and for an instant stunning him. Then Leclère leaped upon him with his feet, and sprang up and down, striving to grind him into the earth. Both Diable's hind legs were broken ere Leclère ceased that he might catch breath.

"A-a-ah! A-a-ah!" he screamed,

incapable of articulate speech, shaking his fist through sheer impotence of

throat and larynx.

"A-a-ah! A-a-ah!" he screamed,

incapable of articulate speech, shaking his fist through sheer impotence of

throat and larynx.But Diable was indminatable. He lay there in a hideous, helpless welter, his lip feebly lifting and writhing to the snarl he had not the strength to utter. Leclère kicked him, and the tired jaws closed on the ankle but could not break the skin.

Then Leclère picked up the whip and proceeded almost to cut him to pieces, at each stroke of the lash crying: "Dis taim Ah break you! Eh? By Gar, Ah break you!"

In the end, exhausted, fainting from loss of blood, he crumpled up and fell by his victim, and, when the wolf-dogs closed in to take their vengeance, with his last consciousness dragged his body on top of Diable to shield him from their fangs.

This occurred not far from Sunrise, and the missionary, opening the door to Leclère a few hours later, was surprised to note the absence of Diable from the team. Nor did his surprise lessen when Leclère threw back the robes from the sled, gathered Diable into his arms, and staggered across the threshold. It happened that the surgeon of McQuestion was up on a gossip, and between them they proceeded to repair Leclère.

"Merci, non," said he. "Do you fix firs' de dog. To die? Non. Eet is not good. Becos' heem Ah mus' yet break. Dat fo' w'at he mus' not die."

The surgeon called it a marvel, the missionary a miracle, that Leclère lived through at all; but so weakened was he that in the spring the fever got him and he went on his back again. The dog had been in even worse plight, but his grip on life prevailed, and the bones of his hind legs knitted and his internal organs righted themselves during the several weeks he lay strapped to the floor. And by the time Leclère, finally convalescent, sallow and shaky, took the sun by the cabin door, Diable had reasserted his supremacy and brought not only his own team-mates but the missionary's dogs into subjection.

He moved never a muscle nor twitched a hair when for the first time Leclère tottered out on the missionary's arm and sank down slowly and with infinite caution on the three-legged stool.

"Bon!" he said. "Bon! De good sun!" And he stretched out his wasted hands and washed them in the warmth.

Then his gaze fell on the dog, and the old light blazed back in his eyes. He touched the missionary lightly on the arm. "Mon pére, dat is one beeg devil, dat Diable. You will bring me one pistol, so dat Ah drink the sun in peace."

And thenceforth, for many days, he sat in the sun before the cabin door. He never dozed, and the pistol lay always across his knees. The dog had a way, the first thing each day, of looking for the weapon in its wonted place. At sight of it he would lift his lip faintly in token that he understood, and Leclère would lift his own lip in an answering grin. One day the missionary took note of the trick. "Bless me!" he said. "I really believe the brute comprehends."

Leclère laughed softly. "Look you, mon pére. Dat w'at Ah now spik, to dat does he lissen."

As if in confirmation, Diable just perceptibly wriggled his lone ear up to catch the sound.

"Ah say 'keel'——"

Diable growled deep down in his throat, the hair bristled along his neck, and every muscle went tense and expectant.

"Ah lift de gun, so, like dat——" And suiting action to word, he sighted the pistol at the dog.

Diable, with a single leap sidewise, landed around the corner of the cabin out of sight.

"Bless me!" the missionary remarked. "Bless me!" he repeated at intervals, unconscious of his paucity of expression.

Leclère grinned proudly.

"But why does he not run away?"

The Frecnchman's shoulders went up in a racial shrug which means all things from total ignorance to infinite understanding.

"Then why do you not kill him?"

Again the shoulders went up.

"Mon pére," he said, after a pause, "de taim is not yet. He is one beeg devil. Some taim Ah break heem, so, an' so, all to leetle bits. Heh? Some taim. Bon!"

A day came when Leclère gathered his dogs together and floated down in a bateau to Forty Mile and on to the Porcupine, where he took a commission from the P. C. Company and went exploring for the better part of a year. After that he poled up the Koyokuk to deserted Arctic City, and later came drifting back, from camp to camp, along the Yukon. And during the long months Diable was well lessoned. He learned many tortures—the torture of hunger, the torture of thirst, the torture of fire, and, worst of all, the torture of music.

Like the rest of his kind, he did not enjoy music. It gave him exquisite anguish, racking him nerve by nerve and ripping apart every fiber of his being. It made him howl, long and wolf-like, as when the wolves bay the stars on frosty nights. He could not help howling. It was his one weakness in the contest with Leclère, and it was his shame. Leclère, on the other hand, passionately loved music—as passionately as he loved strong drink. And when his soul clamored for expression, it usually uttered itself in one or both of the two ways. And when he had drunk, not too much but just enough for the perfect poise of exaltation, his brain alit with unsung song and the devil in him aroused and rampant, his soul found its supreme utterance in the bearding of Diable.

"Now we will haf a leetle museek," he would say. "Eh? W'at you t'ink, Diable?"

It was only an old and battered harmonica, tenderly treasured and patiently repaired; but it was the best that money could buy, and out of its silver reeds he drew weird, vagrant airs which men had never heard before. Then the dog, dumb of throat, with teeth tight-clenched, would back away, inch by inch, to the farthest cabin corner. And Leclère, playing, playing, a stout club tucked handily under his arm, followed the animal up, inch by inch, step by step, till there was no further retreat.

At first Diable would crowd himself into the

smallest possible space, groveling close to the floor; but as the music came

nearer and nearer he was forced to uprear, his back jammed into the logs, his

fore legs fanning the air as though to beat off the rippling waves of sound.

He still kept his teeth together, but severe muscular contractions attacked his

body, strange twitchings and jerkings, till he was all aquiver and writing in

silent torment. As he lost control, his jaws spasmodically wrenched apart and

deep, throaty vibrations issued forth, too low in the register of sound for

human ear to catch. And then, as he stood reared with nostrils distended, eyes

dilated, slaver dripping, hair bristling in helpless rage, arose the long

wolf-howl. It came with a slurring rush upward, swelling to a great

heartbreaking burst of sound and dying away in sadly cadenced woe—then

the next rush upward, octave upon octave; the bursting heart; and the infinite

sorrow and misery, fainting, fading, falling, and dying slowly away.

It was fit for hell. And Leclère, with

fiendish ken, seemed to divine each particular nerve and heartstring and, with

long wails and tremblings and sobbing minors, to make it yield up its last

least shred of grief. It was frightful, and for twenty-four hours after, the

dog was nervous and unstrung, starting at common sounds, tripping over his own

shadow, but withal, vicious and masterful with his team-mates. Nor did he show

signs of a breaking spirit. Rather did he grow more grim and taciturn, biding

his time with an inscrutable patience which began to puzzle and weigh upon

Leclère. The dog would lie in the firelight, motionless, for hours,

gazing straight before him at Leclère and hating him with his bitter

eyes.

Often the man felt that he had bucked up against

the very essence of life—the unconquerable essence that swept the hawk

down out of the sky like a feathered thunderbolt, that drove the great gray

goose across the zones, that hurled the spawning salmon through two thousand

miles of boiling Yukon flood. At such times he felt impelled to express his own

unconquerable essence; and with strong drink, wild music and Diable, he

indulged in vast orgies, wherein he pitted his puny strength in the face of

things and challenged all that was, and had been, as was yet to be. "Dere

is somet'ing dere," he affirmed, when the rhythmed vagaries of his mind

touched the secret chords of the dog's being and brought forth the long,

lugubrious howl. "Ah pool eet out wid bot' my han's, so, an' so. Ha! Ha!

Eet is fonee! Eet is ver' fonee! De mans swear, de leetle bird go peep-peep,

Diable heem go yow-yow—an' eet is all de ver' same t'ing."

Father Gautier, a worthy priest, once reproved

him with instances of concrete perditions. He never reproved him again.

"Eet may be so, mon pére," he

made answer. "An' Ah t'ink Ah go troo hell a-snappin', lak de hemlock troo

de fire. Eh, mon pére?"

But all bad things come to an end as well as

good, and so with Black Leclère. On the summer low-water, in a

poling-boat, he left McDougall for Sunrise. He left McDougall in company with

Timothy Brown, and arrived at Sunrise by himself. Further, it was known that

they had quarreled just previous to pulling out; for the "Lizzie," a

wheezy ten-ton sternwheeler, twenty-four hours behind, beat Leclère in

by three days. And when he did get in, it was with a clean-drilled bullet-hole

through his shoulder-muscle and a tale of ambush and murder.

A strike had been made at Sunrise, and things had

changed considerably. With the infusion of several hundred gold-seekers, a deal

of whisky, and half a dozen equipped gamblers, the missionary had seen the page

of his years of labor with the Indians wiped clean. When the squaws became

preoccupied with cooking beans and keeping the fire going for the wifeless

miners, and the bucks with swapping their warm furs for black bottles and

broken timepieces, the took to his bed, said "Bless me!" several

times, and departed to his final accounting in a rough-hewn oblong box.

Whereupon the gamblers moved their roulette and faro tables into the

mission-house, and the click of chips and clink of glasses went up from dawn

till dark and to dawn again.

Now Timothy Brown was well beloved among these

adventurers of the north. The one thing against him was his quick temper and

ready fist—a little thing, for which his kind heart and forgiving hand

more than atoned. On the other hand, there was nothing to atone for Black

Leclère. He was "black," as more than one remembered deed bore

witness, while he was as well hated as the other was beloved. So the men of

Sunrise put a dressing on his shoulder and haled him before Judge Lynch.

It was a simple affair. He had quarreled with

Timothy Brown at McDougall. With Timothy Brown he had left McDougall. Without

Timothy Brown he had arrived at Sunrise. Considered in the light of his

evilness, the unanimous conclusion was that he had killed Timothy Brown. On the

other hand, Leclère acknowledged their facts, but challenged their

conclusion and gave his own explanation. Twenty miles out of Sunrise he and

Timothy Brown were poling the boat along the rocky shore. From that shore two

rifle-shots rang out. Timothy Brown pitched out of the boat and went down

bubbling red, and that was the last of Timothy Brown. He, Leclère,

pitched into the bottom of the boat with a stinging shoulder. He lay very

quietly, peeping at the shore. After a time two Indians stuck up their heads

and came out to the water's edge, carrying between them a birch-bark canoe. As

they launched it, Leclère let fly. He potted one, who went over the side

after the manner of Timothy Brown. The other dropped into the bottom of the

canoe, and then canoe and poling-boat went down the stream in a drifting

battle. Only they hung up on a split current, and the canoe passed on one side

of an island, the poling-boat on the other. That was the last of the canoe, and

he came on into Sunrise. Yes, from the way the Indian in the canoe jumped, he

was sure he had potted him. That was all.

This explanation was not deemed adequate. They

gave him ten hours' grace while the "Lizzie" steamed down to

investigate. Ten hours later she came wheezing back to Sunrise. There had been

nothing to investigate. No evidence had been found to back up his statements.

They told him to make his will, for he possessed a fifty-thousand-dollar

Sunrise claim and they were a law-abiding as well as a law-giving breed.

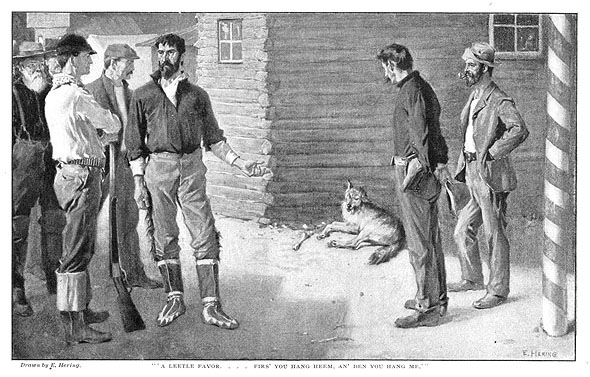

Leclère shrugged his shoulders. "Bot

one t'ing," he said; "a leetle, w'at you call, favor—a leetle

favor, dat is eet. I gif my feefty t'ousan' dollair to de church. I gif my

husky-dog, Diable, to de devil. De leetle favor? Firs' you hang heem, an' den

you hang me. Eet is good, eh?"

Good it was, they agreed, that Hell's Spawn

should break trail for his master across the last divide, and the court was

adjourned down to the river-bank, where a big spruce-tree stood by itself.

Slackwater Charley put a hangman's knot in the end of a hauling-line, and the

noose was slipped over Leclère's head and pulled tight around his neck.

His hands were tied behind his back, and he was assisted to the top of a

cracker-box. Then the running end of the line was passed over an overhanging

branch, drawn taut, and made fast. To kick the box out from under would leave

him dancing on the air.

"Now for the dog," said Webster Shaw,

sometime mining engineer. "You'll have to rope him, Slackwater."

Leclère grinned. Slackwater took a chew of

tobacco, rove a running noose, and proceeded leisurely to coil a few turns in

his hand. He paused once or twice to brush particularly offensive mosquitoes

from off his face. Everybody was brushing mosquitoes, except Leclère,

about whose head a small cloud was distinctly visible. Even Diable, lying

full-stretched on the ground, with his fore paws rubbed the pests away from

eyes and mouth.

But while Slackwater waited for Diable to lift

his head, a faint call came down the quiet air and a man was seen waving his

arms and running across the flat from Sunrise. It was the storekeeper.

"C-call 'er off, boys," he panted, as

he came in among them. "Little Sandy and Bernadotte's jes' got in,"

he explained with returning breath. "Landed down below an' come up by the

short cut. Got the Beaver with 'm. Picked 'm up in his canoe, stuck in a back

channel, with a couple of bullet-holes in 'm. Other buck was Klog-Kutz, the one

that knocked spots out of his squaw and dusted."

"Eh? W'at Ah say? Eh?" Leclère

cried exultantly. "Dat de one fo' sure! Ah know. Ah spik true."

"The thing to do is to teach these damned

Siwashes a little manners," spoke Webster Shaw. "They're getting fat

and sassy, and we'll have to bring them down a peg. Round in all the bucks and

string up the Beaver for an object-lesson. That's the program. Come on and

let's see what he's got to say for himself."

"Heh, m'sieu'!" Leclère called,

as the crowd began to melt away through the twilight in the direction of

Sunrise, "Ah lak ver' moch to see de fon."

"Oh, we'll turn you loose when we come

back," Webster Shaw shouted over his shoulder. "In the mean time,

meditate on your sins and the ways of Providence. It will do you good, so be

grateful."

As is the way with men who are accustomed to

great hazards, whose nerves are healthy and trained to patience, so

Leclère settled himself down to the long wait—which is to say that

he reconciled his mind to it. There was no settling for the body, for the

taught rope forced him to stand rigidly erect. The least relaxation of the

leg-muscles pressed the rough-fibered noose into his neck, while the upright

position caused him much pain in his wounded shoulder. He projected his under

lip and expelled his breath upward along his face to blow the mosquitoes away

from his eyes. But the situation had its compensation. To be snatched from the

maw of death was well worth a little bodily suffering, only it was unfortunate

that he should miss the hanging of the Beaver.

And so he mused, till his eyes chanced to fall

upon Diable, head between fore paws and stretched on the ground asleep. And

then Leclère ceased to muse. He studied the animal closely, striving to

sense if the sleep were real or feigned. The dog's sides were heaving

regularly, but Leclère felt that the breath came and went a shade too

quickly; also he felt there was a vigilance or an alertness to every hair which

belied unshackling sleep. He would have given his Sunrise claim to be assured

that the dog was not awake, and once, when one of his joints cracked, he looked

quickly and guiltily at Diable to see if he roused.

He did not rouse then, but a few minutes later he

got up slowly and lazily, stretched, and looked carefully about him.

"Sacrédam!" said Leclère under his breath.

Assured that no one was in sight or hearing,

Diable sat down, curled his upper lip almost into a smile, looked up at

Leclère, and licked his chops.

"Ah see my feenish," the man said, and

laughed sardonically aloud.

Diable came nearer, the useless ear wobbling, the

good ear cocked forward with devilish comprehension. He thrust his head on one

side, quizzically, and advanced with mincing, playful steps. He rubbed his body

gently against the box till it shook and shook again. Leclère teetered

carefully to maintain his equilibrium.

"Diable," he said calmly, "look

out. Ah keel you."

Diable snarled at the word and shook the box with

greater force. Then he upreared and with his fore paws threw his weight against

it higher up. Leclère kicked out with one foot, but the rope bit into

his neck and checked so abruptly as nearly to overbalance him.

"Hi! Ya! Chook! Mush-on!" he

screamed.

Diable retreated for twenty feet or so, with a

fiendish levity in his bearing which Leclère could not mistake. He

remembered the dog's often breaking the scum of ice on the water-hole by

lifting up and throwing his weight upon it; and remembering, he understood what

he now had in mind. Diable faced about and paused. He showed his white teeth in

a grin, which Leclère answered; and then hurled his body through the air

straight for the box.

Fifteen minutes later, Slackwater Charley and

Webster Shaw, returning, caught a glimpse of a ghostly pendulum swinging back

and forth in the dim light. As they hurriedly drew in closer, they made out the

man's inert body, and a live thing that clung to it, and shook and worried, and

gave to it the swaying motion.

"Hi! Ya! Chook! you Spawn of Hell!"

yelled Webster Shaw.

Diable glared at him, and snarled threateningly,

without loosing his jaws.

Slackwater Charley got out his revolver, but his

hand was shaking as with a chill and he fumbled.

"Here, you take it," he said, passing the weapon over.

Webster Shaw laughed shortly, drew a sight

between the gleaming eyes, and pressed the trigger. Diable's body twitched with

the shock, thrashed the ground spasmodically a moment, and went suddenly limp.

But his teeth still held fast-locked.

From the June 1902 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.