Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() T must not be thought from what I have at various times told of the

Greek fishermen that they were altogether bad. Far from it. But they were rough

men, gathered together in isolated communities, and fighting with the elements

for a livelihood. They lived far away from the law and its workings, did not

understand it, and thought it tyranny.

T must not be thought from what I have at various times told of the

Greek fishermen that they were altogether bad. Far from it. But they were rough

men, gathered together in isolated communities, and fighting with the elements

for a livelihood. They lived far away from the law and its workings, did not

understand it, and thought it tyranny.

Especially did the fish laws seem tyrannical; and

because of this the men of the fish patrol were looked upon by them as their

natural enemies.

But it is to show that they could act generously

as well as hate bitterly that this story of Demetrios Contos is told.

Demetrios Contos lived in Vallejo. Next to

"Big Alec," he was the largest, bravest and most influential man

among the Greeks. He had given us no trouble, and probably would never have

clashed with us had he not invested in a new salmon-boat.

He had had it built upon his own model, in which

the lines of the usual salmon-boat were somewhat modified.

To his high elation he found his new boat very

fast—in fact, faster than any other boat on the bay or rivers. Forthwith

he grew proud and boastful; and our raid with the Mary Rebecca on the

Sunday salmon-fishers having wrought fear in their hearts, he sent a challenge

up to Benicia.

One of the local fishermen told us of it, and it

was to the effect that Demetrios Contos would sail up from Vallejo on the

following Sunday, and in the plain sight of Benicia set his net and catch

salmon, and that Charley Le Grant, patrolman, might come and get him if he

could.

Sunday came. The challenge had been bruited

abroad, and the fishermen and seafaring folk of Benicia turned out to a man,

crowding Steamboat Wharf till it looked like the grand stand at a

football-match.

In the afternoon, when the sea-breeze had picked

up in strength, the Greek's sail hove into view as he bowled along before the

wind. He tacked a score of feet from the wharf, waved his hand theatrically,

like a knight about to enter the lists, received a hearty cheer in return, and

stood away into the straits for a couple of hundred yards.

Then he lowered sail, and drifting the boat

sidewise by means of the wind, proceeded to set his net.

He did not set much of it, possibly fifty feet,

yet Charley and I were thunderstruck by the man's effrontery.

We did not know at that time, but we learned

afterward that what he used was an old and worthless net. It could catch

fish, true; but a catch of any size would have torn it into a thousand

pieces.

Charley shook his head and said, "I confess

it puzzles me. What if he has out only fifty feet? He could never get it in if

we once started for him. And why does he come here, anyway, flaunting his

lawbreaking in our faces?"

In the meantime the Greek was lolling in the

stern of his boat and watching the net-floats. When a large fish is meshed in a

gill-net the floats by their agitation advertise the fact. And they evidently

advertised it to Demetrios, for he now pulled in about a dozen feet of net, and

held aloft for a moment, before he flung it into the bottom of the boat, a big,

glistening salmon.

It was greeted by the audience on the wharf with

round after round of cheers.

This was more than Charley could stand.

"Come on, lad!" he called to me; and we

lost no time jumping into our salmon-boat and getting up sail.

The crowd shouted warning to Demetrios, and as we

darted out from the wharf we saw him slash his worthless net clear with a long

knife.

His sail was all ready to go up, and a moment

later it fluttered in the sunshine. He ran aft, drew in the sheet, and filled

on the long tack toward the Contra Costa hills.

By this time we were not more than thirty feet

astern. Charley was jubilant. He knew our boat was fast, and he knew, further,

that in fine sailing few men were his equals. He was confident that we should

surely catch Demetrios, and I shared his confidence. But somehow we did not

seem to gain.

It was a pretty sailing breeze. We were gliding

sleekly through the water, but Demetrios was sliding away from us. And not only

was he going faster, but he was eating into the wind a fraction of a point

closer than we. This was sharply impressed upon us when he went about under the

Contra Costa hills and passed us on the other tack fully one hundred feet dead

to windward.

"Whew!" Charley exclaimed. "Either

that boat is a wonder or there's a five-gallon coal-oilcan fast to our

keel!"

It certainly looked it, one way or the other; and

by the time Demetrios made the Sonoma hills, on the other side of the straits,

we were so hopelessly outdistanced that Charley told me to slack off the sheet,

and we squared away for Benicia.

The fishermen on Steamboat Wharf showered us with

ridicule when we returned and tied up our boat.

Charley and I got out and walked away, feeling

rather sheepish, for it is a sore stroke to your pride when you think you have

a good boat and know how to sail it and another man comes along and beats

you.

Charley mooned over it for a couple of days; then

word was brought to us, as before, that on the next Sunday Demetrios Contos

would repeat his performance. Charley roused himself. He had our boat out of

the water, cleaned and repainted its bottom, made a trifling alteration about

the centerboard, overhauled the running-gear, and sat up nearly all of Saturday

night, sewing on a new and much larger sail. So large did he make it, in truth,

that additional ballast was imperative, and we stowed away nearly five hundred

pounds of old railroad iron in the bottom of the boat.

Sunday came, and with it came Demetrios Contos.

Again we had the afternoon sea-breeze, and again Demetrios cut loose for forty

or more feet of his rotten net, and got up sail and under way under our very

noses. But he had anticipated Charley's move, and his own sail peaked higher

than ever, while a whole extra cloth had been added to the leech.

By the time we had made the return tack to the

Sonoma hills we could not fail to see that, while we footed it at about equal

speed, Demetrios had eaten the least bit into the wind more than we.

Of course Charley could have drawn his revolver

and fired at Demetrios, but we had long since found it contrary to our natures

to shoot at a fleeing man guilty of a petty offense.

Also, a sort of tacit agreement seemed to have

been reached between the patrolmen and the fishermen. If we did not shoot while

they ran away, they, in turn, did not fight if we once laid hands on them.

Thus Demetrios Contos ran away from us, and we

did no more than try very hard to overtake him; and in turn, if our boat proved

faster than his, or was sailed better, he would, we knew, make no resistance

when we caught up with him.

But it was vain undertaking for us to attempt to

catch him.

"Slack away the sheet!" Charley

commanded; and as we fell off before the wind, Demetrios's mocking laugh

floated down to us.

Charley shook his head, saying, "It's no

use. Demetrios has the better boat. If he tries his performance again we must

meet it with some new scheme."

This time it was my imagination which came to the

rescue.

"What's the matter," I suggested, on

the Wednesday following, "with my chasing Demetrios in the boat next

Sunday, and with your waiting for him on the wharf at Vallejo?"

Charley considered it a moment and slapped his

knee.

"A good idea! You're beginning to use that

head of yours. But everybody'll know I've gone to Vallejo, and you can depend

upon it that Demetrios will know, too."

"No," I replied. "On Sunday you

and I will be round Benicia up to the very moment Demetrios's sail heaves into

sight. This will lull everybody's suspicions. Then, when Demetrios's sail does

heave in sight, you stroll leisurely away and up-town. All the fishermen will

think you're beaten, and that you know you're beaten."

"So far, so good," Charley commented,

while I paused to catch breath.

"When you're once out of sight," I

continued, "you leg it for all you're worth for Dan Maloney's. Take that

little mare of his, and strike out on the county road for Vallejo. The road's

in fine condition, and you can make it in quicker time than Demetrios can beat

all the way down against the wind."

"And I'll arrange right away for the mare,

first thing in the morning," Charley said.

As usual, Sunday and Demetrios Contos arrived

together. It had become the regular thing for the fishermen to assemble on

Steamboat Wharf to greet his arrival and laugh at our discomfiture. He lowered

sail two hundred yards out, and set his customary fifty feet of rotten net.

"I suppose this nonsense will keep up as

long as his old net holds out!" Charley grumbled, with intention, in the

hearing of several of the Greeks. "Well, so long, lad!" Charley

called to me, a moment later. "I think I'll go up-town to

Maloney's."

"Let me take the boat out?" I

asked.

"If you want to," was his answer, as he

turned on his heel and walked slowly away.

Demetrios pulled two large salmon out of his net,

and I jumped into the boat. The fishermen crowded round in a spirit of fun, and

when I started to get up sail, overwhelmed me with all sorts of jocular

advice.

But I was in no hurry. I waited to give Charley

all the time I could, and I pretended dissatisfaction with the stretch of the

sail, and slightly shifted the small tackle by which the sprit forces up the

peak. It was not until I was sure that Charley had reached Dan Maloney's that I

cast off from the wharf and gave the big sail to the wind. A stout puff filled

it and suddenly pressed the lee gunwale down till a couple of buckets of water

came aboard.

A little thing like this will happen to the best

small-boat sailors, and yet, although I instantly let go the sheet and righted,

I was cheered sarcastically, as if I had been guilty of a very awkward

blunder.

When Demetrios saw only one person in the

fish-patrol boat, and that one a boy, he proceeded to play with me. Making a

short tack out, he returned, with his sheet a little free, to the Steamboat

Wharf. And there he made short tacks, and turned and twisted and ducked round,

to the great delight of his sympathetic audience.

I was right behind him all the time, and I dared

to do whatever he did, even when he squared away before the wind and jibed his

big sail over—a most dangerous trick with such a sail in such a wind.

He dpended upon the brisk sea-breeze and strong

ebb-tide, which together kicked up a nasty sea, to bring me to grief. But I was

on my mettle, and if I do say it, never in all my life did I sail a boat better

than on that day.

It was Demetrios who came to grief instead.

Something went wrong with his centerboard, so that it jammed in the case and

would not go all the way down.

In a short breathing-space, which he had gained

from me by a clever trick, I saw him working impatiently with the centerboard,

trying to force it down. I gave him little time, and he was compelled quickly

to return to the tiller and sheet.

The centerboard made him anxious. He gave over

playing with me and started on the long beat to Vallejo.

To my joy, on the first long track across, I

found that I could eat into the wind just a little closer than he. Here was

where another man in the boat would have been of value, for with me but a few

feet astern, he did not dare let go the tiller and run amidships to try to

force down the centerboard.

Unable to hang on as close in the eye of the wind

as formerly, he proceeded to slack his sheet a trifle and to ease off a bit, in

order to outfoot me. This I permitted him to do till I worked to windward, when

I bore down upon him.

As I drew close, he fainted at coming about. This

led me to shoot into the wind to forestall him. But it was only a feint,

cleverly executed, and he held back to his course while I hurried to make up

lost ground.

He was undeniably abler than I when it came to

manœuvering. Time after time I all but had him, and each time he tricked

me and escaped. Besides, the wind was freshening constantly, and each of us had

our hands full to avoid a capsize.

The strong ebb-tide, racing down the straits in

the teeth of the wind, cause and unusually heavy and spiteful sea, which dashed

aboard continually. I was dripping wet, and even the sail was wet half-way up

the leech. Once I did succeed in outmanœuvering Demetrios, so that my bow

bumped into him amidships.

Here was where I should have had another man.

Before I could run forward and leap aboard he shoved the boats apart with an

oar, laughing mockingly in my face as he did so.

We were now at the mouth of the straits, in a bad

stretch of water. Here the Vallejo Strait and the Karquines Strait drove

directly at each other.

Through the first flowed all the water of Napa

River and the great tide-lands; through the second flowed all the water of

Suisun Bay and the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. And where such immense

bodies of water, flowing swiftly, rushed together, a terrible tide-rip was

produced.

To make it worse, the wind howled up San Pablo

Bay for fifteen miles, and drove in a tremendous sea upon the tide-rip.

Conflicting currents tore about in all

directions, colliding, forming whirlpools, sucks and boils, and shooting up

spitefully into waves, which fell aboard as often from leeward as from

windward. And through it all, confused, driven into a madness of motion,

thundered the great, smoking seas from San Pablo Bay.

I was as wildly excited as the water. The boat

was behaving splendidly, leaping and lurching through the welter like a

race-horse. I could hardly contain myself with the joy of it.

And just then, as I roared along like a

conquering hero, the boat received a frightful smash, and came instantly to a

dead stop. I was flung forward and into the bottom.

As I sprang up I caught a fleeting glimpse of a

greenish, barnacle-covered object, and knew it at once for what it

was—that terror of navigation, a sunken pile.

No man may guard against such a thing.

Water-logged and floating just beneath the surface, it was impossible to sight

it in the troubled water in time to escape.

The whole bow of the boat must have been crushed

in, for in a very few seconds the boat was half-full. Then a couple of seas

filled it and it sank straight down, dragged to the bottom by the heavy

ballast. So quickly did it all happen that I was entangled in the sail and

drawn under. When I fought my way to the surface, suffocating, lungs almost

bursting, I could see nothing of the oars. They must have been swept away by

the chaotic currents. I saw Demetrios Contos looking back from his boat, and

heard the vindictive and mocking tones of his voice, as he shouted exultantly.

He held steadily on his course, leaving me to perish.

There was nothing to do but swim for it, which,

in that wild confusion, was at the best a matter of but a few moments.

Holding my breath and working with my hands, I

managed to get off my heavy sea-boots and my jacket. Yet there was very little

breath I could catch to hold, and I swiftly discovered that it was not so much

a matter of swimming as of breathing.

I was beaten and buffeted, smashed under by the

great San Pablo whitecaps, and strangled by the hollow tide-rip waves which

flung themselves into my eyes, nose and mouth. Then the strange sucks would

grip by legs and drag me under, to spout me up in some fierce boiling, where,

even as I tried to catch my breath, a great whitecap would crash down upon

me.

It was impossible to survive any length of time.

I was breathing more water than air, and drowning all the time. My senses began

to leave me, my head to whirl. I struggled on, spasmodically, instinctively,

and was barely half-conscious, when I felt myself caught by the shoulders and

hauled over the gunwale of a boat.

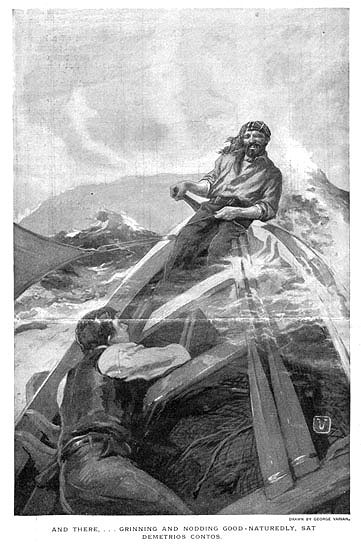

For some time I lay across a seat, where I had

been flung, face downward, and with the water running out of my mouth. After a

while, still weak and faint, I turned around to see who was my rescuer. And

there, in the stern, sheet in one hand and tiller in the other, grinning and

nodding good-naturedly, sat Demetrios Contos.

He had intended to let me drown,—he said so

afterward,—but his better self had fought the battle, conquered, and sent

him back to me.

"You alla right?" he asked.

I managed to shape a "Yes" with my

lips, although I could not yet speak.

"You saila de boat verra gooda," he

said. "So gooda as a man."

A compliment from Demetrios Contos was a

compliment indeed, and I keenly appreciated it, although I could only nod my

head in acknowledgment.

We held no more conversation, for I was busy

recovering and he was busy with the boat. He ran in to the wharf at Vallejo,

made the boat fast and helped me out. Then it was, as we both stood on the

wharf, that Charley stepped out from behind a net-rack and put his hand on

Demetrios Contos's arm.

"He saved my life, Charley," I

protested, "and I don't think he ought to be arrested."

A puzzled expression came into Charley's face,

which cleared immediately in a way it had when he made up his mind.

"I can't help it, lad," he said,

kindly. "I can't go back on my duty, and it's my plain duty to arrest him.

To-day is Sunday; there are two salmon in his boat which he caught to-day. What

else can I do?"

"But he saved my life," I persisted,

unable to make any other argument.

Demetrios Contos's face was black with rage when

he learned Charley's decision. He had a sense of being unfairly treated. He had

performed a generous act and saved a helpless enemy, and in return the enemy

was taking him to jail.

Charley and I were out of sorts with each other

when we went back to Benicia. I stood for the spirit of the law and not the

letter; but by the letter Charley made his stand.

So far as he could see, there was nothing else

for him to do.

The law said distinctly that no salmon should be

caught on Sunday. He was a patrolman, and it was his duty to enforce the law.

That was all there was to it.

Two days later we went down to Vallejo to the

trial. I had to go along as a witness, and it was the most hateful task that I

ever performed in my life when I testified on the witness-stand to seeing

Demetrios catch the two salmon.

Demetrios had engaged a lawyer, but his case was

hopeless. The jury was out only fifteen minutes, and returned a verdict of

guilty. The judge sentenced Demetrios to pay a fine of one hundred dollars or

be sent to jail for fifty days.

Charley stepped quickly up to the clerk of the

court.

"I want to pay that fine," he said, at

the same time placing five twenty-dollar gold pieces on the desk.

"It—it was the only way out of it, lad," he said, turning to

me.

The moisture rushed into my eyes as I seized his

hand.

"I want to pay —" I began.

"To pay your half?" he interrupted.

"I certainly shall expect you to pay it."

In the meantime Demetrios had been informed by

his lawyer that his fee had likewise been paid by Charley.

Demetrios came over to shake Charley's hand, and

all his warm southern blood flamed in his face.

Then, not to be outdone in generosity, he

insisted on paying his fine and his lawyer's fee himself, and flew half-way

into a passion because Charley refused to let him.

More than anything else we ever did, I think, did

this action of Charley's impress upon the fishermen the deeper significance of

the law. Also Charley was raised high in their estimation, while I came in for

a little share of praise as a boy who knew how to sail a boat. Demetrios Contos

not only never broke the law again, but became a very good friend of ours, and

on more than one occasion he ran up to Benicia to have a gossip with us.

From the April 27, 1905 issue of The Youth's Companion magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.