Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() you vas in der old country ships, a liddle shaver like you vood wait

on der able seamen. Und ven der able seaman sing oug, 'Boy, der water-jug!' you

vood jump quick, like a shot, und bring der water-jug. Und ven der able seaman

sing out, 'Boy, my boots!' you vood get der boots. Und you vood pe politeful,

und say 'Yessir!' und 'No sir!.' But you pe in der American ship, und you t'ink

you are so good as der able seamen. Chris, mine boy, I haf ben a sailorman for

twenty-two years, und do you t'ink you are so good as me? I vas a sailorman

pefore you vas borned, und I knot und reef und splice ven you play mit

top-strings und fly kites."

you vas in der old country ships, a liddle shaver like you vood wait

on der able seamen. Und ven der able seaman sing oug, 'Boy, der water-jug!' you

vood jump quick, like a shot, und bring der water-jug. Und ven der able seaman

sing out, 'Boy, my boots!' you vood get der boots. Und you vood pe politeful,

und say 'Yessir!' und 'No sir!.' But you pe in der American ship, und you t'ink

you are so good as der able seamen. Chris, mine boy, I haf ben a sailorman for

twenty-two years, und do you t'ink you are so good as me? I vas a sailorman

pefore you vas borned, und I knot und reef und splice ven you play mit

top-strings und fly kites."

"But you are unfair, Emil!" cried Chris

Farrington, his sensitive face flushed and hurt. He was a slender though

strongly built young fellow of seventeen, with Yankee ancestry writ large all

over him.

"Dere you go vonce again!" the Swedish

sailor exploded. "My name is Mister Johansen, und a kid of a boy like you

call me 'Emil!' It vas insulting, und comes pecause of der American

ship!"

"But you call me 'Chris!'" the boy

expostulated, reproachfully.

"But you vas a boy."

"Who does a man's work," Chris

retorted. "And because I do a man's work I have as much right to call you

by your first name as you me. We are all equals in this fo'c'sle, and you know

it. When we signed for the voyage in San Francisco, we signed as sailors on the Sophie Sutherland, and there was no difference made with any of us.

Haven't I always done my work? Did I ever shirk? Did you or any other man ever

have to take a wheel for me? Or a lookout? Or go aloft?"

"Chris is right," interrupted a young

English sailor. "No man has had to do a tap of his work yet. He signed as

good as any of us, and he's shown himself as good ——"

"Better!" broke in a Nova Scotia man.

"Better than some of us! When we struck the sealing-grounds he turned out

to be next to the best boat-steerer aboard. Only French Louis, who'd been at it

for years, could beat him. I'm only a boat-puller, and you're only a

boat-puller, too, Emil Johansen, for all your twenty-two years at sea. Why

don't you become a boat-steerer?"

"Too clumsy," laughed the Englishman,

"and too slow."

"Little that counts, one way or the

other," joined in Dane Jurgensen, coming to the aid of his Scandinavian

brother. "Emil is a man grown and an able seaman; the boy is

neither."

And so the argument raged back and forth, the

Swedes, Norwegians and Danes, because of race kinship, taking the part of

Johansen, and the English, Canadians and Americans taking the part of Chris.

From an unprejudiced point of view, the right was on the side of Chris. As he

had truly said, he did a man's work, and the same work that any of them did.

But they were prejudiced, and badly so, and out of the words which passed rose

a standing quarrel which divided the forecastle into two parties.

The Sophie Sutherland was a seal-hunter,

registered out of San Francisco, and engaged in hunting the furry sea-animals

along the Japanese coast north to Bering Sea. The other vessels were two-masted

schooners, but she was a three-master and the largest in the fleet. In fact,

she was a full-rigged, three-topmast schooner, newly built.

Although Chris Farrington knew that justice was

with him, and that he performed all his work faithfully and well, many a time,

in secret thought, he longed for some pressing emergency to arise whereby he

could demonstrate to the Scandinavian seamen that he also was an able

seaman.

But one stormy night, by an accident for which he

was in nowise accountable, in overhauling a spare anchor-chain he had all the

fingers of his left hand badly crushed. And his hopes were likewise crushed,

for it was impossible for him to continue hunting with the boats, and he was

forced to stay idly aboard until his fingers should heal. Yet, although he

little dreamed it, this very accident was to give him the long looked-for

opportunity.

One afternoon in the latter part of May the

Sophie Sutherland rolled sluggishly in a breathless calm. The seals were

abundant, the hunting good, and the boats were all away and out of sight. And

with them was almost every man of the crew. Besides Chris, there remained only

the captain, the sailing-master and the Chinese cook.

The captain was captain only by courtesy. He was

an old man, past eighty, and blissfully ignorant of the sea and its ways; but

he was the owner of the vessel, and hence the honorable title. Or course, the

sailing-master, who was really captain, was a thoroughgoing seaman. The mate,

whose post was aboard, was out with the boats, having temporarily taken Chris's

place as boat-steerer.

When good weather and good sport came together,

the boats were accustomed to range far and wide, and often did not return to

the schooner until long after dark. But for all that it was a perfect hunting

day, Chris noted a growing anxiety on the part of the sailing-master. He paced

the deck nervously, and was constantly sweeping the horizon with his marine

glasses. Not a boat was in sight. As sunset arrived, he even sent Chris aloft

to the mizzen-topmast-head, but with no better luck. The boats could not

possibly be back before midnight.

Since noon the barometer had been falling with

startling rapidity, and all the signs were ripe for a great storm—how great,

not even the sailing-master anticipated. He and Chris set to work to prepare

for it. They put storm gaskets on the furled topsails, lowered and stowed the

foresail and spanker and took in the two inner jibs. In the one remaining jib

they put a single reef, and a single reef in the mainsail.

Night had fallen before they finished, and with

the darkness came the storm. A low moan swept over the sea, and the wind struck

the Sophie Sutherland flat. But she righted quickly, and with the

sailing-master at the wheel, sheered her bow into within five points of the

wind. Working as well as he could with his bandaged hand, and with the feeble

aid of the Chinese cook, Chris went forward and backed the jib over to the

weather side. This, with the flat mainsail, left the schooner hove to.

"God help the boats! It's no gale! It's a

typhoon!" the sailing-master shouted to Chris at eleven o'clock. "Too

much canvas! Got to get two more reefs into that mainsail, and got to do it

right away!" He glanced at the old captain, shivering in oilskins at the

binnacle and holding on for dear life. "There's only you and I, Chris—and

the cook; but he's next to worthless!"

In order to make the reef, it was necessary to

lower the mainsail, and the removal of this after pressure was bound to make

the schooner fall off before the wind and sea because of the forward pressure

of the jib.

"Take the wheel!" the sailing-master

directed. "And when I give the word, hard up with it! And when she's

square before it, steady her! And keep her there! We'll heave to again as soon

as I get the reefs in!"

Gripping the kicking spokes, Chris watched him

and the reluctant cook go forward into the howling darkness. The Sophie

Sutherland was plunging into the huge head-seas and wallowing tremendously,

the tense steel stays and taut rigging humming like harp-strings to the wind. A

buffeted cry came to his ears, and he felt the schooner's bow paying off of its

own accord. The mainsail was down!

He ran the wheel hard-over and kept anxious track

of the changing direction of the wind on his face and of the heave of the

vessel. This was the crucial moment. In performing the evolution she would have

to pass broadside to the surge before she could get before it. The wind was

blowing directly on his right cheek, when he felt the Sophie Sutherland

lean over and begin to rise toward the sky—up—up—an infinite distance! Would

she clear the crest of the gigantic wave?

Again by the feel of it, for he could see

nothing, he knew that a wall of water was rearing and curving far above him

along the whole weather side. There was an instant's calm as the liquid wall

intervened and shut off the wind. The schooner righted, and for that instant

seemed at perfect rest. Then she rolled to meet the descending rush.

Chris shouted to the captain to hold tight, and

prepared himself for the shock. But the man did not live who could face it. An

ocean of water smote Chris's back, and his clutch on the spokes was loosened as

if it were a baby's. Stunned, powerless, like a straw on the face of a torrent,

he was swept onward he knew not whither. Missing the corner of the cabin, he

was dashed forward along the poop runway a hundred feet or more, striking

violently against the foot of the foremast. A second wave, crushing inboard,

hurled him back the way he had come, and left him half-drowned where the poop

steps should have been.

Bruised and bleeding, dimly conscious, he felt

for the rail and dragged himself to his feet. Unless something could be done,

he knew the last moment had come. As he faced the poop the wind drove into his

mouth with suffocating force. This fact brought him back to his senses with a

start. The wind was blowing from dead aft! The schooner was out of the trough

and before it! But the send of the sea was bound to broach her to again.

Crawling up the runway, he managed to get to the wheel just in time to prevent

this. The binnacle light was still burning. They were safe!

That is, he and the schooner were safe. As to the

welfare of his three companions he could not say. Nor did he dare leave the

wheel in order to find out, for it took every second of his undivided attention

to keep the vessel to her course. The least fraction of carelessness and the

heave of the sea under the quarter was liable to thrust her into the trough.

So, a boy of one hundred and forty pounds, he clung to his Herculean task of

guiding the two hundred straining tons of fabric amid the chaos of the great

storm forces.

Half an hour later, groaning and sobbing, the

captain crawled to Chris's feet. All was lost, he whimpered. He was smitten

unto death. The galley had gone by the board, the mainsail and running-gear,

the cook, everything!

"Where's the sailing-master?" Chris

demanded, when he caught breath after steadying a wild lurch of the schooner.

It was no child's play to steer a vessel under single-reefed jib before a

typhoon.

"Clean up for'ard," the old man

replied. "Jammed under the fo'c'sle-head, but still breathing. Both his

arms are broken, he says, and he doesn't know how many ribs. He's hurt

bad."

"Well, he'll drown there the way she's

shipping water through the hawse-pipes. Go for'ard!" Chris commanded,

taking charge of things as a matter of course. "Tell him not to worry;

that I'm at the wheel. Help him as much as you can, and make him help—"

he stopped and ran the spokes to starboard as a tremendous billow rose under

the stern and yawed the schooner to port—"and make him help himself for

the rest. Unship the fo'c'sle-hatch and get him down into a bunk. Then ship the

hatch again."

The captain turned his aged face forward and

wavered pitifully. The waist of the ship was full of water to the bulwarks. He

had just come through it, and knew death lurked every inch of the way.

"Go!" Chris shouted, feebly. And as the

fear-stricken man started, "And take another look for the cook!"

Two hours later, almost dead from suffering, the

captain returned. He had obeyed orders. The sailing-master was helpless

although safe in a bunk; the cook was gone. Chris sent the captain below to the

cabin to change his clothes.

After interminable hours of toil, day broke cold

and gray. Chris looked about him. The Sophie Sutherland was racing

before the typhoon like a thing possessed. There was no rain, but the wind

whipped the spray of the sea mast-high, obscuring everything except in the

immediate neighborhood.

Two waves only could Chris see at a time—the one

before and the one behind. So small and insignificant the schooner seemed on

the long Pacific roll! Rushing up a maddening mountain, she would poise like a

cockle-shell on the giddy summit, breathless and rolling, leap outward and down

into the yawning chasm beneath, and bury herself in the smother of foam at the

bottom. Then the recovery, another mountain, another sickening upward rush,

another poise, and the downward crash! Abreast of him, to starboard, like a

ghost of the storm, Chris saw the cook dashing apace with the schooner.

Evidently, when washed overboard, he had grasped and become entangled in a

trailing halyard.

For three hours more, alone with this gruesome

companion, Chris held the Sophie Sutherland before the wind and sea. He

had long since forgotten his mangled fingers. The bandages had been torn away,

and the cold, salt spray had eaten into the half-healed wounds until they were

numb and no longer pained. But he was not cold. The terrific labor of steering

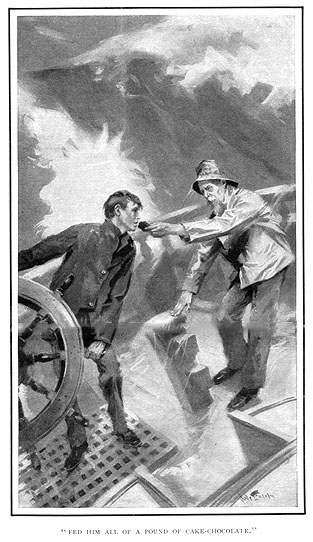

forced the perspiration from every pore. Yet he was faint and weak with hunger

and exhaustion, and hailed with delight the advent on deck of the captain, who

fed him all of a pound of cake-chocolate. It strengthened him at once.

He ordered the captain to cut the halyard by

which the cook's body was towing, and also to go forward and cut loose the

jib-halyard and sheet. When he had done so, the jib fluttered a couple of

moments like a handkerchief, then tore out of the belt-ropes and vanished. The

Sophie Sutherland was running under bare poles.

By noon the storm had spent itself, and by six in

the evening the waves had died down sufficiently to let Chris leave the helm.

It was almost hopeless to dream of the small boats weathering the typhoon, but

there is always the chance in saving human life, and Chris at once applied

himself to going back over the course along which he had fled. He managed to

get a reef in the spanker, and then, with the aid of the watch-tackle, to hoist

them to the stiff breeze that yet blew. And all through the night, tacking back

and forth on the back track, he shook out the canvas as fast as the wind would

permit.

The injured sailing-master had turned delirious,

and between tending him and lending a hand with the ship, Chris kept the

captain busy. "Taught me more seamanship," as he afterward said,

"than I'd learned on the whole voyage." But by daybreak the old man's

feeble frame succumbed, and he fell off into exhausted sleep on the weather

poop.

Chris, who could now lash the wheel, covered the

tired man with blankets from below, and went fishing in the lazaretto for

something to eat. But by the day following he found himself forced to give in,

drowsing fitfully by the wheel and waking ever and anon to take a look at

things.

On the afternoon of the third day he picked up a

schooner, dismasted and battered. As he approached, close-hauled on the wind,

he saw her decks crowded by an unusually large crew, and on sailing closer,

made out among others the faces of his missing comrades. And he was just in the

nick of time, for they were fighting a losing fight at the pumps. An hour later

they, with the crew of the sinking craft, were aboard the Sophie

Sutherland.

Having wandered so far from their own vessel,

they had taken refuge on the strange schooner just before the storm broke. She

was a Canadian sealer on her first voyage, and as was now apparent, her

last.

The captain of the Sophie Sutherland had a

story to tell, also, and he told it well—so well, in fact, that when all hands

were gathered together on deck during the dog-watch, Emil Johansen strode over

to Chris and gripped him by the hand.

"Chris," he said, so loudly that all

could hear, "Chris, I gif in. You vas yoost so good a sailorman as I. You

vas a bully boy und able seaman, und I be proud for you!

"Und Chris!" He turned as if he had

forgotten something, and called back, "From dis time always you call me

'Emil' mitout der 'Mister!'"

From the May 23, 1901 issue of The Youth's Companion magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.