Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() ALT

first blinked his eyes in the light of day in a trading post on the Yukon

River. Masters, his father, was one of those world missionaries who are known

as "pioneers," and who spend the years of their life in pushing

outward the walls of civilizations and in planting the wilderness. He had

selected Alaska as his field of labor, and his wife had gone with him to that

land of frost and cold.

ALT

first blinked his eyes in the light of day in a trading post on the Yukon

River. Masters, his father, was one of those world missionaries who are known

as "pioneers," and who spend the years of their life in pushing

outward the walls of civilizations and in planting the wilderness. He had

selected Alaska as his field of labor, and his wife had gone with him to that

land of frost and cold.

Now, to be born to the moccasin and pack-strap is

indeed a hard way of entering the world, but far harder it is to lose one's

mother while yet a child. This was Walt's misfortune when he was fourteen years

old.

He had, at different times, done deeds which few

boys get the chance to do, and he had learned to take some pride in himself and

to be unafraid. With most people pride goeth before a fall; but not so with

Walt. His was a healthy belief in his own strength and fitness, and knowing his

limitations, he was neither overweening nor presumptuous. He had learned to

meet reverses with the stoicism of the Indian. Shame, to him, lay not in the

failure to accomplish, but in the failure to strive. So, when he attempted to

cross the Yukon between two ice-runs, and was chased by the trail, he was not

cast down by his defeat.

The way of it was this. After passing the winter

at his father's claim on Mazy May, he came down to an island on the Yukon and

went into camp. This was late in the spring, just before the breaking of the

ice on the river. It was quite warm, and the days were growing marvelously

long. Only the night before, when he was talking with Chilkoot Jim, the

daylight had not faded and sent him off to bed till ten o'clock. Even Chilkoot

Jim, an Indian boy who was about Walt's own age, was surprised at the rapidity

with which summer was coming on. The snow had melted from all the southern

hillsides and the level surfaces of the flats and islands; everywhere could be

heard the trickling of water and the song of hidden rivulets; but somehow,

under its three-foot ice-sheet, the Yukon delayed to heave its great length of

three thousand miles and shake off the frosty fetters which bound it.

But it was evident that the time was fast

approaching when it would again run free. Great fissures were splitting the ice

in all directions, while the water was beginning to flood through them and over

the top. On this morning a frightful rumbling brought the two boys hurriedly

from their blankets. Standing on the bank, they soon discovered the cause. The

Stewart River had broken loose and reared a great ice barrier, where it entered

the Yukon, barely a mile above their island. While a great deal of the Stewart

ice had been thus piled up, the remainder was now flowing under the Yukon ice,

pounding and thumping at the solid surface above it as it passed onward toward

the sea.

"To-day um break um," Chilkoot Jim

said, nodding his head. "Sure!"

"And then maybe two days for the ice to pass

by," Walt added, "and you and I'll be starting for Dawson. It's only

seventy miles, and if the current runs five miles an hour and we paddle three,

we ought to make it inside of ten hours. What do you think?"

"Sure!" Chilkoot Jim did not know much

English, and this favorite word of his was made to do duty on all

occasions.

After breakfast, the boys got out the

Peterborough canoe from its winter cache. It was an admirable sample of the

boat-builder's skill, an imported article brought from the natural home of the

canoe—Canada. It had been packed over the Chilkoot Pass, two years before, on

a man's back, and had then carried the first mail in six months into the

Klondike. Walt, who happened to be in Dawson at the time, had bought it for

three hundred dollars' worth of dust which he had mined on the Mazy May.

It had been a revelation, both to him and to

Chilkoot Jim, for up to its advent they had been used to no other craft than

the flimsy birch-bark canoes of the Indians and the rude polling-boats of the

whites. Jim, in fact, spent many a happy half-hour in silent admiration of its

perfect lines.

"Um good. Sure!" Jim lifted his gaze

from the dainty craft, expressing his delight in the same terms of the

thousandth time. But glancing over Walt's shoulder, he saw something on the

river which startled him. "Look! See!" he cried.

A man had been racing a dog-team across the

slushy surface for the shore, and had been cut off by the rising flood. As Walt

whirled round to see, the ice behind the man burst into violent commotion,

splitting and smashing into fragments which bobbled up and down and turned

turtle like so many corks.

A gush of water followed, burying the sled and

washing the dogs from their feet. Tangled in their harness and securely

fastened to the heavy sled, they must drown in a few minutes unless rescued by

the man. Bravely his manhood answered.

Floundering about with the drowning animals,

nearly hip-deep in the icy flood, he cut and slashed with his sheath-knife at

the traces. One by one the dogs struck out for shore, the first reaching safety

ere the last was released. Then the master, abandoning the sled, followed them.

It was a struggle in which little help could be given, and Walt and Chilkoot

Jim could only, at the last, grasp his hands and drag him, half-fainting, up

the bank.

First he sat down till he had recovered his

breath; next he knocked the water from his ears like a boy who had just been

swimming; and after that he whistled his dogs together to see whether they had

all escaped. These things done, he turned his attention to the lads.

"I'm Muso," he said, "Pete Muso,

and I'm looking for Charley Drake. His partner is dying down at Dawson, and

they want him to come at once, as soon as the river breaks. He's got a cabin on

this island, hasn't he?"

"Yes," Walt answered, "but he's

over on the other side of the river, with a couple of other men, getting out a

raft of logs for a grub-stake."

The stranger's disappointment was great.

Exhausted by his weary journey, just escaped from sudden death, overcome by all

he had undergone in carrying the message which was now useless, he looked

dazed. The tears welled into his eyes, and his voice was choked with sobs as he

repeated, aimlessly, "But his partner's dying. It's his partner, you know,

and he wants to see him before he dies."

Walt and Jim knew that nothing could be done, and

as aimlessly looked out on the hopeless river. No man could venture on it and

live. On the other bank, and several miles up-stream, a thin column of smoke

wavered to the sky. Charley Drake was cooking his dinner there; seventy miles

below, his partner lay dying; yet no word of it could be sent.

But even as they looked, a change came over the

river. There was a muffled rending and tearing, and, as if by magic, the

surface water disappeared, while the great ice-sheet, reaching from shore to

shore, and broken into all manner and sizes of cakes, floated silently up

toward them. The ice which had been pounding along underneath had evidently

grounded at some point lower down, and was now backing up the water like a

mill-dam. This had broken the ice-sheet from the land and lifted it on top of

the rising water.

"Um break up very quick," Chilkoot Jim

said.

"Then here goes!" Muso cried, at the

same time beginning to strip his wet clothes.

The Indian boy laughed. "Mebbe you get um in

middle, mebbe not. All the same, the trail um go down-stream, and you go, too.

Sure!" He glanced at Walt, that he might back him up in preventing this

insane attempt.

"You're not going to try and make it

across?" Walt queried.

Muso nodded his head, sat down, and proceeded to

unlace his moccasins.

"But you mustn't!" Walt protested.

"It's certain death. The river'll break before you get half-way, and then

what good'll your message be?"

But the stranger doggedly went on undressing,

muttering in an undertone, "I want Charley Drake! Don't you understand?

It's his partner, dying."

"Um sick man. Bimeby —— " The Indian boy

put a finger to his forehead and whirled his hand in quick circles, thus

indicating the approach of brain fever. "Um work too hard, and um think

too much, all the time think about sick man at Dawson. Very quick um head go

round—so." And he feigned the bodily dizziness which is caused by a

disordered brain.

By this time, undressed as if for a swim, Muso

rose to his feet and started for the bank. Walt stepped in front, barring the

way. He shot a glance at his comrade. Jim nodded that he understood and would

stand by.

"Get out of my way, boy!" Muso

commanded, roughly, trying to thrust him aside.

But Walt closed in, and with the aid of Jim

succeeded in tripping him upon his back. He struggled weakly for a few moments,

but was too wearied by his long journey to cope successfully with the two boys

whose muscles were healthy and trail-hardened.

"Pack um into camp, roll um in plenty

blanket, and I fix um good," Jim advised.

This was quickly accomplished, and the sufferer

made as comfortable as possible. After he had been attended to, and Jim had

utilized the medical lore picked up in the camps of his own people, they fed

the stranger's dogs and cooked dinner. They said very little to each other, but

each boy was thinking hard, and when they went out into the sunshine a few

minutes later, their minds were intent on the same project.

The river had now risen twenty feet, the ice

rubbing softly against the top of the bank. All noise had ceased. Countless

millions of tons of ice and water were silently waiting the supreme moment,

when all bonds would be broken and the mad rush to the sea would begin.

Suddenly, without the slighted apparent effort, everything began to move

downstream. The jam had broken.

Slowly at first, but faster and faster the frozen

sea dashed past. The noise returned again, and the air trembled to a mighty

churning and grinding. Huge blocks of ice were shot into the air by the

pressure; others butted wildly into the bank; still others, swinging and

pivoting, reached inshore and swept rows of pines away as easily as if they

were so many matches.

In awe-stricken silence the boys watched the

magnificent spectacle, and it was not until the ice had slackened its speed and

fallen to its old level that Walt cried, "Look, Jim! Look at the trail

going by!"

And in truth it was the trail going by—the trail

upon which they had camped and traveled during all the preceding winter. Next

winter they would journey with dogs and sleds over the same ground, but not on

the same trail. That trail, the old trail, was passing away before their

eyes.

Looking up-stream, they saw open water. No more

ice was coming down, although vast quantities of it still remained on the upper

reaches, jammed somewhere amid the maze of islands which covered the Yukon's

breast. As a matter of fact, there were several more jams yet to break, one

after another, and to send down as many ice-runs. The next might come along in

a few minutes; it might delay for hours. Perhaps there would be time to paddle

across. Walt looked questioningly at his comrade.

"Sure!" Jim remarked, and without

another word they carried the canoe down the bank. Each knew the danger of what

they were about to attempt, but they wasted no speech over it. Wild life had

taught them both that the need of things demanded effort and action, and that

the tongue found its fit vocation at the camp-fire when the day's work was

done.

With dexterity born of long practice they

launched the canoe, and were soon making it spring to each stroke of the

paddles as they stemmed the muddy current. A steady procession of lagging

ice-cakes, each thoroughly capable of crushing the Peterborough like an

egg-shell, was drifting on the surface, and it required of the boys the utmost

vigilance and skill to thread them safely.

Anxiously they watched the great bend above, down

which at any moment might rush another ice-run. And as anxiously they watched

the ice stranded against the bank and towering a score of feet above them. Cake

was poised upon cake and piled in precarious confusion, while the boys had to

hug the shore closely to avoid the swifter current of midstream. Now and again

great heaps of this ice tottered and fell into the river, rolling and rumbling

like distant thunder, and lashing the water into fair-sized tidal waves.

Several times they were nearly swamped, but saved

themselves by quick work with the paddles. And all the time Charley Drake's

pillared camp smoke grew nearer and clearer. But it was still on the opposite

shore, and they knew they must get higher up before they attempted to shoot

across.

Entering the Stewart River, they paddled up a few

hundred yards, shot across, and then continued up the right bank of the Yukon.

Before long they came to the Bald-Face Bluffs—huge walls of rock which rose

perpendicularly from the river. Here the current was swiftest inshore, forming

the first serious obstacle encountered by the boys. Below the bluffs they

rested from their exertions in a favorable eddy, and then, paddling their

strongest, strove to dash past.

At first they gained, but in the swiftest place

the current overpowered them. For a full sixty seconds they remained

stationary, neither advancing nor receding, the grim cliff base within reach of

their arms, their paddles dipping and lifting like clockwork, and the rough

water dashing by in muddy haste. For a full sixty seconds, and then the canoe

sheered in to the shore. To prevent instant destruction, they pressed their

paddles against the rocks, sheered back into the stream, and were swept away.

Regaining the eddy, they stopped for breath. A second time they attempted the

passage; but just as they were almost past, a threatening ice-cake whirled down

upon them on the angry tide, and they were forced to flee before it.

"Um stiff, I think yes," Chilkoot Jim

said, mopping the sweat from his face as they again rested in the eddy.

"Next time um make um, sure."

"We've got to. That's all there is about

it," Walt answered, his teeth set and lips tight-drawn, for Pete Muso had

set a bad example, and he was almost ready to cry from exhaustion and failure.

A third time they darted out of the head of the eddy, plunged into the swirling

waters, and worked a snail-like course ahead. Often they stood still for the

space of many strokes, but whatever they gained they held, and they at last

drew out into easier water far above. But every moment was precious. There was

no telling when the Yukon would again become a scene of wild anarchy in which

neither man nor any of his works could hope to endure. So they held steadily to

their course till they had passed above Charley Drake's camp by a quarter of a

mile. The river was fully a mile wide at this point, and they had to reckon on

being carried down by the swift current in crossing it.

Walt turned his head from his place in the bow.

Jim nodded. Without further parley they headed the canoe out from the shore, at

an angle of forty-five degrees against the current. They were on the last

stretch now; the goal was in fair sight. Indeed, as they looked up from their

toil to mark their progress, they could see Charley Drake and his two comrades

come town to the edge of the river to watch them.

Five hundred yards; four hundred yards; the

Peterborough cut the water like a blade of steel; the paddles were dipping,

dipping, dipping in rapid rhythm—and then a warning shout from the bank sent a

chill to their hearts. Round the great bend just above rolled a mighty wall of

glistening white. Behind it, urging it on to lightning speed, were a million

tons of long-pent water.

The right flank of the ice-run, unable to get

cleanly round the bend, collided with the opposite shore, and even as they

looked they saw the ice mountains rear toward the sky, rise, collapse, and rise

again in glittering convulsions.  The advancing roar filled the air so that Walt

could not make himself heard; but he paused long enough to wave his paddle

significantly in the direction of Dawson. Perhaps Charley Drake, seeing, might

understand.

The advancing roar filled the air so that Walt

could not make himself heard; but he paused long enough to wave his paddle

significantly in the direction of Dawson. Perhaps Charley Drake, seeing, might

understand.

With two swift strokes they whirled the

Peterborough down-stream. They must keep ahead of the rushing flood. It was

impossible to make either bank tat that moment. Every ounce of their strength

went into the paddles, and the frail canoe fairly rose and leaped ahead at each

stroke. They said nothing. Each knew and had faith in the other, and they were

too wise to waste their breath. The shore-line—trees, islands and the Stewart

River—flew by at a bewildering rate, but they barely looked at it.

Occasionally Chilkoot Jim stole a glance behind

him at the pursuing trail, and marked the fact that they held their own. Once

he shaped a sharper course toward the bank, but found the trail was overtaking

them, and gave it up.

Gradually they worked in to land, their failing

strength warning them that it was soon or never. And at last, when they did

draw up to the bank, they were confronted by the inhospitable barrier of the

stranded shore-ice. Not a place could be found to land, and with safety

virtually within arm's reach, they were forced to flee on down the stream. They

passed a score of places, at each of which, had they had plenty of time, they

could have clambered out; but behind pressed on the inexorable trail, and would

not let them pause.

Half a mile of this work drew heavily upon their

strength; and the trail came upon them nearer and nearer. Its sullen grind was

in their ears, and its collisions against the bank made one continuous

succession of terrifying crashes. Walt felt his heart thumping against his ribs

and caught each breath in painful gasps. But worst of all was the constant

demand upon his arms.

If he could only rest for the space of one

stroke, he felt that the torture would be relieved; but no, it was dip and

lift, dip and lift, till it seemed as if at each stroke he would surely die.

But he knew that Chilkoot Jim was suffering likewise; and their lives depended

each upon the other; and that it would be a blot upon his manhood should he

fail or even miss a stroke.

They were very weary, but their faith was large,

and if either felt afraid, it was not of the other, but of himself.

Flashing round a sharp point, they came upon

their last chance for escape. An island lay close inshore, upon the nose of

which the ice lay piled in a long slope. They drove the Peterborough half out

of the water upon a shelving cake and leaped out. Then, dragging the canoe

along, slipping and tripping and falling, but always getting nearer the top,

they made their last mad scramble.

As they cleared the crest and fell within the

shelter of the pines, a tremendous crash announced the arrival of the trail.

One huge cake, shoved to the, shoved to the top of the rim-ice, balanced

threateningly above them and then toppled forward.

With one jerk they flung themselves and the canoe

from beneath, and again fell, breathless and panting for air. The thunder of

the ice-run came dimly to their ears; but they did not care. It held no

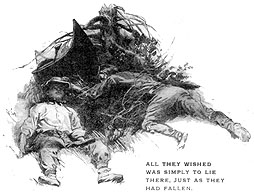

interest for them whatsoever. All they wished was simply to lie there, just as

they had fallen, and enjoy the inaction of repose.

Two hours later, when the river once more ran

open, they carried the Peterborough down to the water. But just before they

launched it, Charley Drake and a comrade paddled up in another canoe.

"Well, you boys hardly deserve to have good

folks out looking for you, the way you've behaved," was his greeting.

"What under the sun made you leave your tent and get chased by the trail?

Eh? That's what I'd like to know."

It took but a minute to explain the real state of

affairs, and but another to see Charley Drake hurrying along on his way to his

sick partner at Dawson.

"Pretty close shave, that," Walt

Masters said, as they prepared to get aboard and paddle back to camp.

"Sure!" Chilkoot Jim replied, rubbing

his stiffened biceps in a meditative fashion.

From the September 26, 1907 issue of The Youth's Companion magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.