Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() HARLEY called

it a "coup," having heard Neil Partington use the term; but I think

he misunderstood the word, and thought it meant "coop," to catch, to

trap.

HARLEY called

it a "coup," having heard Neil Partington use the term; but I think

he misunderstood the word, and thought it meant "coop," to catch, to

trap.

The fishermen, however, coup or coop, must have

called it a Waterloo, for it was the severest stroke ever dealt them by the

fish patrol.

During what is called the "open season"

the fishermen could catch as many salmon as their luck allowed and their boats

could hold. But there was one important restriction. From sundown Saturday

night to sunrise Monday morning they were not permitted to set a net.

This was a wise provision on the part of the fish

commission, for it was necessary to give the spawning salmon some opportunity

to ascend the river and lay their eggs. And this law, with only an occasional

violation, had been obediently observed by the Greek fishermen who caught

salmon for the canneries and the market.

On Sunday morning Charley received a telephone

call from a friend in Collinsville, who told him that the full force of

fishermen were out with their nets. Charley and I jumped into our salmon-boat

and started for the scene of the trouble. With a light, favoring wind we went

through the Karquines Strait, crossed Suisun Bay, passed the Ship Island Light,

and came upon the whole fleet at work.

But first let me describe the method by which

they worked. The net used is what is known as a gill-net. It has a simple,

diamond-shaped mesh, which measures at least seven and one-half inches between

the knots. From five to seven and even eight hundred feet in length, these nets

are only a few feet wide. They are not stationary, but float with the current,

the upper edge supported on the surface by floats, the lower edge sunk by means

of leaden weights.

This arrangement keeps the net upright in the

current and effectually prevents all but the smaller fish from ascending the

river. The salmon, swimming near the surface, as is their custom, run their

heads through these meshes, and are prevented from going on through by their

larger girth of body, and from going back because of their gills, which catch

in the mesh.

It requires two fishermen to set such a net: one

to row the boat, while the other, standing in the stern, carefully plays out

the net. When it is all out, stretching directly across the stream, the men

make their boat fast to one end of the net and drift along with it.

As we drew closer to the fleet, we observed none

of the usual flurry and excitement which our appearance invariably produced.

Instead, each boat lay quietly to its net, while the fishermen favored us with

not the slightest attention.

This did not continue to be the case, however,

for as we bore down upon the nearest net, the men to whom it belonged detached

their boat and rowed slowly toward the shore. The rest of the boats showed no

sign of uneasiness.

"That's funny," was Charley's remark.

"But we can confiscate the net, at any rate."

We lowered sail, picked up one end of the net,

and began to heave it into the boat. But at the first heave we heard a bullet

zip-zipping past us on the water, followed by the faint report of a

rifle. The men who had rowed ashore were shooting at us.

Charley took a turn round a pin and sat down.

There were no more shots. But as soon as he began to heave in, the shooting

recommenced.

"That settles it," he said, flinging

the end of the net overboard. "You fellows want it worse than we do, and

you can have it."

We rowed over toward the next net, for Charley

was intent on finding out whether or not we were face to face with an organized

defiance.

As we approached, the two fishermen proceeded to

cast off from their net and row ashore, while the first two rowed back and made

fast to the net we had abandoned. And at the second net we were greeted by

rifle-shots till we desisted and went on to the third, where the manœuver

was again repeated.

Then we gave it up, completely routed, hosted

sail and started on the long windward beat back to Benicia. A number of Sundays

went by, on each of which the law was persistently violated. Yet, unless we had

an armed force of soldiers, we could do nothing. The fishermen had hit upon a

new idea, and were using it for all it was worth, while there seemed no way by

which we could get the better of them.

Then one morning the idea came. We were down on

the steamboat wharf, where the river steamers made their landings, and where we

found a group of amused longshoremen and loafers listening to the tale of a

sleepy-eyed young fellow in long sea-boots. He was a sort of amateur fisherman,

he said, fishing for the local market of Berkeley. Now Berkeley was on the

Lower Bay, thirty miles away. On the previous night, he said, he had set his

net and dozed off to sleep in the bottom of the boat.

That was the last he remembered. The next he knew

it was morning, and he opened his eyes to find his boat rubbing softly against

the piles of Steamboat Wharf at Benicia. Also, he saw the river streamer,

Apache, lying ahead of him, and a couple of deck-hands disentangling the

shreds of his net from the paddle-wheel.

IN short, after he had fallen asleep his

fisherman's riding-light had gone out, and the Apache had run over his

net. After tearing it pretty well to pieces, in some way it still remained

foul, and he had been given a thirty mile tow.

Charley nudged me with his elbow. I grasped his

thought on the instant, but objected:

"We can't charter a steamboat."

"Don't intent to," he rejoined.

"But let's run over to Turner's shipyard. I've something in mind there

that may be of use to us."

Over we went to the shipyard, where Charley led

the way to the Mary Rebecca, lying hauled out on the ways, where she had

been generally cleaned and overhauled.

She was a scow-schooner we both knew well,

carrying a cargo of one hundred and forty tones and a spread of canvas greater

than any other schooner on the bay.

"How d'ye do, Ole?" Charley greeted a

big blue-shirted Swede who was greasing the jaws of the main-gaff with a piece

of pork-rind.

Ole Ericsen verified Charley's conjecture that

the Mary Rebecca, as soon as launched, would run up the San Joaquin

River nearly to Stockton for a load of wheat. Then Charley made his

proposition, and Ole Ericsen shook his head.

"Just a hook, one good-sized hook,"

Charley pleaded. "We can put the end of the hook through the bottom from

the outside, and fasten it on the inside with a nut. After it's done its work,

why, all we have to do is to go down into the hold, unscrew the nut, and out

drops the hook. Then drive a wooden peg into the hole, and the Mary

Rebecca is all right again."

Ole Ericsen was obstinate for a time; but in the

end, after we had had dinner with him, he was brought round to consent.

"Ay do it!" he said, striking one huge

fist into the palm of the other hand. "But yust hurry you up with der

hook. Der Mary Revecca slides into der water to-night."

It was Saturday, and Charley had need to hurry.

We went to the shipyard blacksmith shop, where, under Charley's directions, a

most generously curved hook of heavy steel was made.

Back we hastened to the Mary Rebecca. Aft

of the great centerboard case, through what was properly her keel, a hold was

bored. The end of the hook was inserted for the outside, and Charley, on the

inside, screwed the nut on tightly. As it stood complete, the hook projected

more than a foot beneath the bottom of the schooner. Its curve was something

like the curve of a sickle, but deeper.

The next morning found the sun shining brightly,

but something more than a half-gale shrieking up the Karquines Strait. The

Mary Rebecca got under way with two reefs in her mainsail and one in her

foresail. It was rough in the strait and in Suisun Bay, but as the water grew

more landlocked it became quite calm, although there was no let-up in the

wind.

Off Ship Island Light the reefs were shaken out,

and at Charley's suggestion a big fisherman's staysail was made all ready for

hoisting, and the maintopsail, bunched into a cap at the masthead, was

overhauled so that it could be set on an instant's notice.

We were tearing along before the wind as we came

upon the salmon fleet. There they were, boats and nets, strung out evenly over

the river as far as we could see. A narrow space on the right-hand side of the

channel was left clear for steamboats, but the rest of the river was covered

with the wide-stretching nets. This narrow space was our logical course, but

Charley, at the wheel, steered the Mary Rebecca straight for the

nets.

"Now she takes it!" Charley cried, as

we dashed across the middle of a line of floats which marked a net.

At one end of this line was a small barrel buoy,

at the other end the two fishermen in their boat. Buoy and boat at once began

to draw together, and the fishermen cried out as they were jerked after us. A

couple of minutes later we hooked a second net, and then a third as we tore

straight through the center of the fleet.

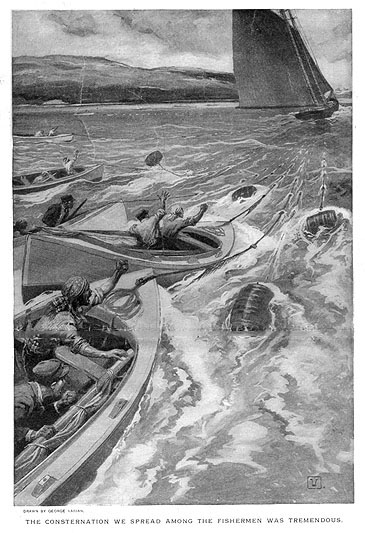

The consternation we spread among the fishermen

was tremendous. As fast as we hooked a net the two ends of it, buoy and boat

came together as they dragged out astern; and so many buoys and boats, coming

together at such breakneck speed, kept the fishermen on the jump to avoid

smashing into one another.

The drag of a single net is very heavy, and even

in such a wind Charley and Ole Ericsen decided that ten was all the Mary

Rebecca could take along with her. So, when we had hooked ten nets, with

ten boats containing twenty men streaming along behind us, we veered to the

left out of the fleet , and headed toward Collinsville.

We were all jubilant. Charley was handling the

wheel as if he were steering the winning yacht home in a race. The two sailors,

who made up the crew of the Mary Rebecca, were grinning and joking. Ole

Ericsen was rubbing his huge hands in childlike glee.

"Ay tank you fish patrol fallers never ben

so lucky as when you sail with Ole Ericsen," he was saying, when a rifle

cracked sharply astern, and a bullet gouged along the newly painted cabin,

glanced on a nail, and sang shrilly onward into space.

This was too much for Ole Ericsen. At sight of

his beloved paintwork thus defaced, he jumped up and shook his fist at the

fishermen; but a second bullet smashed into the cabin not six inches from his

head, and he dropped down to the deck under cover of the rail.

All the fishermen had rifles, and they now opened

a general fusillade. We were all driven to cover, even Charley, who was

compelled to desert the wheel. Had it not been for the heavy drag of the nets,

we would inevitably have broached to at the mercy of the enraged fishermen. But

the nets, fastened to the bottom of the Mary Rebecca well aft, held her

stern into the wind, and she continued to plow on, although somewhat

erratically.

Then Ole Ericsen bethought himself of a large

piece of sheet steel in the empty hold. It was actually a plate from the side

of the New Jersey, a steamer which had recently been wrecked outside the

Golden Gate, and in the salving of which the Mary Rebecca had taken

part.

Crawling carefully along the deck, the two

sailors, Ole and I got the heavy plate on deck and aft, where we reared it as a

shield between the wheel and the fishermen. The bullets whanged and banged

against it, but Charley grinned in its shelter, and coolly went on steering. So

we raced along, behind us a howling screaming bedlam of wrathful Greeks,

Collinsville ahead, and bullets spat-spatting all round us.

"Ole," Charley said, in a faint voice.

"I don't know what we're going to do!"

Ole Ericsen, lying on his back close to the rail

and grinning upward at the sky, turned over on his side and looked at him.

"Ay tank we go into Collinsville yust der same," he said.

"But we can't stop!" Charley groaned.

"I never thought of it, but we can't stop."

A look of consternation slowly overspread Ole

Ericsen's broad face. It was only too true. We had a hornet's nest on our

hands, and to stop at Collinsville would be to have it about our ears.

"Every man Jack of them has a gun," one

of the sailors remarked, cheerfully.

In a few minutes we were at Collinsville, and

went foaming by within biscuit-toss of the wharf.

"I hope the wind holds out," Charley

said.

"What of der wind?" Ole demanded,

disconsolately. "Der river will not hold out, and then ——"

"It's head for the tall timber, and the

Greeks take the hindmost," adjudged the cheerful sailor.

We had now reached a dividing of the ways. To the

left was the mouth of the Sacreamento River, to the right the mouth of the San

Joaquin. The cheerful sailor crept forward and jibed over the foresail as

Charley put the helm to starboard, and we swerved to the right, into the San

Joaquin. The wind, from which we had been running away on an even keel, now

caught us on our beam, and the Mary Rebecca was pressed down on her port

side as if she were about to capsize.

Still we dashed on, and still the fishermen

dashed on behind. The value of their nets was greater than the fines they would

have to pay for violating the fish laws; so to cast off from their nets and

escape, which they could easily do, would profit them nothing. Further, the

desire for vengeance was roused, and we could depend upon it that they would

follow us to the ends of the earth, if we could tow them that far.

The rifle-firing had ceased, and we looked astern

to see what they were doing. The boats were strung along at unequal distances

apart, and we saw the four nearest ones bunching together. This was done by the

boat ahead trailing a small rope astern to the one behind. When this was

caught, they would cast off from their net and heave in on the line till they

were bought up to the boat in front.

So great was the speed at which we were

traveling, however, that this was very slow work. Sometimes the men would

strain to their utmost and fail to get in an inch of the rope; at other times

they came ahead more rapidly.

When the four boats were near enough together for

a man to pass from one to another, one Greek from each of three got into the

nearest boat to us, taking his rifle with him. This made five in the foremost

boat, and it was plain that their intention was to board us. This they

proceeded to do, by main strength and sweat, running hand over hand the

float-line of a net. And although it was slow, and they stopped frequently to

rest, they gradually drew nearer.

Charley smiled at their efforts, and said,

"Give her the topsail, Ole."

The cap at the mainmasthead was broken out, and

sheet and down-haul pulled flat, amid a scattering rifle-fire from the boats;

and the Mary Rebecca laid over and sprang ahead faster than ever.

But the Greeks were undaunted. Unable, at the

increased speed, to draw themselves nearer by means, they rigged from the

blocks of their boat-sail what sailors call a "watch-tackle." One of

them, held by the legs of his mates, would lean far over the bow and make the

tackle fast to the float-line. Then they would heave in on the tackle till the

blocks were together, when the manœuver would be repeated.

"Have to giver her the staysail,"

Charley said.

Ole Ericsen looked at the straining Mary

Rebecca and shook his head. "It will take der masts out of her,"

he said.

"And we'll be taken out of her if you

don't," Charley replied.

Ole shot an anxious glance at his masts, another

at the boat-load of armed Greeks, and consented.

The five men were in the bow of the boat—a bad

place when a craft is towing. I was watching the behavior of their boat as the

great fisherman's staysail, far, far larger than the topsail and used only in

light breezes, was broken out.

As the Mary Rebecca lurched forward with a

tremendous jerk, the nose of the boat ducked down into the water, and the men

tumbled over one another in a wild rush into the stern to save the boat from

being dragged sheer under water.

"That settles them!" Charley remarked,

although he was anxiously studying the behavior of the Mary Rebecca,

which was being driven under far more canvas than it was able to carry

safely.

"Next stop is Antioch!" announced the

cheerful sailor, after the manner of a railway conductor. "And next comes

Merryweather!"

"Come here, quick!" Charley said to

me.

I crawled across the deck and stood upright

beside him in the shelter of the sheet steel.

"Feel inside my inside pocket," he

commanded, "and get my note-book. That's right. Tear out a blank page and

write what I tell you."

This is what I wrote:

Telephone to Merryweather, to the sheriff, the constable or the judge. Tell them we are coming and to turn out the town. Arm everybody. Have them down on the wharf to meet us or we are gone geese.

"Now make it good and fast to that

marlinespike, and stand by to toss it ashore."

I did as he directed. By now we were nearing

Antioch. The wind was shouting through our rigging, the Mary Rebecca was

half-over on her side and rushing ahead like an ocean greyhound. The seafaring

folk of Antioch had seen us, and had hurried to the wharf-ends to find out what

was the matter.

Straight down the water-front we boomed, Charley

edging in till a man could almost leap ashore. When he gave the signal I tossed

the marlinspike.

It all happened in a flash, for the next moment

Antioch was behind, and we were heeling it up to San Joaquin toward

Merryweather, six miles away. The river straightened out here so that our

course lay almost due east, and we squared away before the wind.

We strained our eyes for a glimpse of the town,

and the first sight we caught of it gave us immense relief. The wharves were

black with men. As we came closer, we could see them still arriving, stringing

down the main street on the run, nearly every man with a gun in his hand.

Charley glanced astern at the fishermen with a look of ownership in his eye

which till now had been missing.

The Greeks were plainly overawed by the display

of armed strength, and were putting their own rifles away.

We took in topsail and staysail, dropped the

main-peak, and as we got abreast of the principal wharf jibed the mainsail. The

Mary Rebecca shot round into the wind,—the captive fishermen describing

a great arc behind her,—and forged ahead till she lost way, when lines were

flung ashore and she was made fast.

Ole Ericsen heaved a great sigh. "Ay never

tank Ay see my wife never again," he confessed.

"Why, we were never in any danger,"

said Charley.

Ole looked at him incredulously.

"Sure, I mean it," Charley went on.

"All we had to do any time was to let go our end, as I am doing to now, so

that those Greeks can untangle their nets."

He went below with a monkey-wrench, unscrewed the

nut, and let the hook drop off. When the Greeks had hauled their nets into

their boats and made everything shipshape, a posse of citizens took them off

our hands.

From the April 13, 1905 issue of The Youth's Companion magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.