Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

T will not be so monotonous at sea," I promised my fellow

voyagers on the Snark. "The sea is filled with life. It is so

populous that every day something new is happening. Almost as soon as we pass

through the Golden Gate and head south we'll pick up with the flying-fish.

We'll be having them fried for breakfast. We'll be catching bonito and dolphin,

and spearing porpoises from the bowsprit. And then there are the sharks—sharks

without end."

T will not be so monotonous at sea," I promised my fellow

voyagers on the Snark. "The sea is filled with life. It is so

populous that every day something new is happening. Almost as soon as we pass

through the Golden Gate and head south we'll pick up with the flying-fish.

We'll be having them fried for breakfast. We'll be catching bonito and dolphin,

and spearing porpoises from the bowsprit. And then there are the sharks—sharks

without end."

We passed through the Golden Gate and headed

south. We dropped the mountains of California beneath the horizon, and daily

the sun grew warmer. But there were no flying-fish, no bonito and dolphin. The

ocean was bereft of life. Never had I sailed on so forsaken a sea. Always,

before, in the same latitudes, had I encountered flying-fish.

"Never mind," I said. "Wait till

we get off the coast of Southern California. Then we'll pick up the

flying-fish."

We came abreast of Southern California, abreast

of the Peninsula of Lower California, abreast of the coast of Mexico, and there

were no flying-fish. Nor was there anything else. No life moved. As the days

went by the absence of life became almost uncanny.

"Never mind," I said. "When we do

pick up with the flying-fish we'll pick up with everything else. The

flying-fish is the staff of life for all the other breeds. Everything will come

in a bunch when we find the flying-fish."

When I should have headed the Snark

southwest for Hawaii, I still held her south. I was going to find those

flying-fish. Finally the time came when, if I wanted to go to Honolulu, I

should have headed the Snark due west. Instead of which I kept her

south. Not until latitude 19° did we encounter the first flying-fish. He

was very much alone. I saw him. Five other pairs of eager eyes scanned the sea

all day, but never saw another. So sparse were the flying-fish that nearly a

week elapsed before the last one on board saw his first flying-fish. As for the

dolphin, bonito, porpoise, and all the other hordes of life—there weren't

any.

Not even a shark broke the surface with his

ominous dorsal fin. Bert took a dip daily under the bowsprit, hanging on to the

stays and dragging his body through the water. And daily he canvassed the

project of letting go and having a decent swim. I did my best to deter him. But

with him I had lost all standing as an authority on sea life.

"If there are sharks," he

demanded, "why don't they show up?"

"If there are sharks," he

demanded, "why don't they show up?"

I assured him that if he really did let go and

have a swim the sharks would promptly appear. This was a bluff on my part. I

didn't believe it. It lasted as a deterrent for two days.

The third day the wind fell calm, and it was

pretty hot. The Snark was moving a knot an hour. Bert dropped down under

the bowsprit and let go. And now behold the perversity of things. We had sailed

across two thousand miles and more of ocean and had met with no sharks. Within

five minutes after Bert had finished his swim the fin of a shark was cutting

the surface in circles around the Snark.

There was something wrong about that shark. It

bothered me. It had no right to be there in that deserted ocean. The more I

thought about it, the more incomprehensible it became. But two hours later we

sighted land and the mystery was cleared up. He had come to us from the land,

and not from the uninhabited deep. He had presaged the landfall. He was the

messenger of the land.

Twenty-seven days out from San Francisco we

arrived at the island of Oahu, Territory of Hawaii. In the early morning we

drifted around Diamond Head into full view of Honolulu, and then the ocean

burst suddenly into life. Flying-fish cleaved the air in glittering squadrons.

In five minutes we saw more of them than during the whole voyage. Other fish,

large ones, of various sorts, leaped into the air.

There was life everywhere, on sea and shore. We

could see the masts and funnels of the ships in the harbor, the hotels, and

bathers along the beach at Waikiki, the smoke rising from the dwelling-houses

high up on the volcanic slopes of the Punch Bowl and Tantalus. The custom-house

tug was racing toward us, and a big school of porpoises got under out bow and

began cutting the most ridiculous capers. The port doctor's launch came

charging out at us, and a big sea turtle broke the surface with his back and

took a look at us.

Never was there such a burgeoning of life.

Strange faces were on our decks, strange voices were speaking, and the copies

of that very morning's newspaper, with cable reports from all the world, were

thrust before our eyes. Incidentally, we read the Snark and all hands

had been lost at sea, and that she had been a very unseaworthy craft, anyway.

And while we read this information a wireless message was being received by the

Congressional party on the summit of Haleakala announcing the safe arrival of

the Snark.

It was the Snark's first landfall—and

such a landfall! For twenty-seven days we had been on the deserted deep, and it

was pretty hard to realize that there was so much life in the world. We were

made dizzy by it. We could not take it all in at once. We were like awakened

Rip Van Winkles, and it seemed to us that we were dreaming. On one side the

azure sea lapped across the horizon into the azure sky; on the other side the

sea lifted itself into great breakers of emerald that fell into a snowy smother

upon a white coral beach. Beyond the beach green plantations of sugar-cane

undulated gently upward to steeper slopes, which, in turn, became jaded

volcanic crests, drenched with tropic showers and capped by stupendous masses

of trade-wind clouds.

At any rate it was a most beautiful dream. The

Snark turned and headed directly in toward the emerald surf, till it

lifted and thundered on either hand; and on either hand, scarce a biscuit-toss

away, the reef showed its long teeth, pale green and menacing.

Abruptly the land itself, in a riot of olive

greens of a thousand hues, reached out its arms and folder the Snark in.

There was no perilous passage through the reef, no emerald surf and azure

sea—nothing but warm soft land, a motionless lagoon, and tiny beaches on which

swam dark-skinned tropic children. The sea had disappeared. The Snark's

anchor rumbled the chain through the hawse-pipe, and we lay without movement on

a "lineless, level floor." It was all so beautiful and strange that

we could not accept it as real. On the chart this place was called Pearl

Harbor, but we called it Dream Harbor.

A launch came off to us; in it were members of

the Hawaiian Yacht Club, come to greet us and make us welcome, with true

Hawaiian hospitality, to all they had. They were ordinary men, flesh and blood

and all the rest; but they did not tend to break our dreaming. Our last

memories of men were of United States marshals and of panicky little merchants

with rusty dollars for souls, who, in a reeking atmosphere of soot and

lime-dust, laid grimy hands upon the Snark and held her back from her

world-adventure. But these men who came to meet us were clean men. A healthy

tan was on their cheeks and their eyes were not dazzled and bespectacled from

gazing overmuch at glittering dollar-heaps. No, they merely verified the dream.

They clinched it with their unsmirched souls.

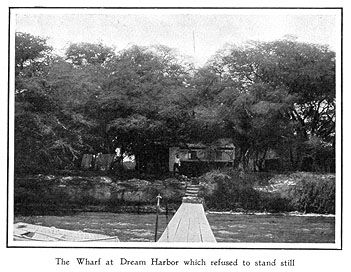

So we went ashore with them across a level,

flashing sea to the wonderful green land. We landed on a tiny wharf, and the

dream became more insistent; for know that for twenty-seven days we had been

rocking across the ocean on the tiny Snark. Not once in all those

twenty-seven days had we known a moment's rest, a moment's cessation from

movement. This ceaseless movement had become ingrained. Body and brain we had

rocked and rolled so long that when we climbed out on the tiny wharf we kept on

rocking and rolling. This, automatically, we attributed to the wharf. It was

projected psychology.

I spraddled along the wharf and nearly fell into

the water. I glanced at Charmian, and they way she walked made me sad. The

wharf had all the seeming of a ship's deck. It lifted, tilted, heaved, and

sank; and since there were no hand-rails on it, it kept Charmian and me busy

avoiding falling in. I never saw such a preposterous little wharf. Whenever I

watched it closely, it refused to roll; but as soon as I took my attention off

of it, away it went, just like the Snark. Once I caught it in the act

just as it upended, and I looked down the length of it for two hundred feet,

and for all the world it was like the deck of a ship ducking into a huge-head

sea.

At last, however, supported by our

hosts, we negotiated the wharf and gained the land. Next we came to a house of

coolness, with great sweeping veranda, where lotus-eaters might dwell. Windows

and doors were wide open to the breeze, and the songs and fragrances blew

lazily in and out. The walls were hung with tapa-cloths. Couches with

grass-woven covers invited everywhere, and there was a grand piano that played,

I was sure, nothing more exciting than lullabies. Servants—Japanese maids in

native costume—drifted around and about, noiselessly, like butterflies.

At last, however, supported by our

hosts, we negotiated the wharf and gained the land. Next we came to a house of

coolness, with great sweeping veranda, where lotus-eaters might dwell. Windows

and doors were wide open to the breeze, and the songs and fragrances blew

lazily in and out. The walls were hung with tapa-cloths. Couches with

grass-woven covers invited everywhere, and there was a grand piano that played,

I was sure, nothing more exciting than lullabies. Servants—Japanese maids in

native costume—drifted around and about, noiselessly, like butterflies.

Everything was preternaturally cool. There was no

blazing down of a tropic sun upon an unshrinking sea. It was too good to be

true. But it was not real. It was a dream-dwelling. I know, for I turned

suddenly and caught the grand piano cavorting in a spacious corner of the room.

I did not say anything, for just then we were being received by a gracious

woman, a beautiful Madonna, clad in flowing white and shod with sandals, who

greeted us as though she had known us always.

We sat at table on the lotus-eating veranda,

served by the butterfly maids, and ate strange foods and partook of a nectar

called poi. But the dream threatened to dissolve. It shimmered and

trembled like an iridescent bubble about to break. I was just glancing out at

the green grass and stately trees and blossoms of hibiscus when suddenly I felt

the table move. The table, and the Madonna across from me, and the veranda of

the lotus-eaters, the scarlet hibiscus, the greensward and the tree—all lifted

and tilted before my eyes, and heaved and sank down into the trough of a

monstrous sea. I gripped my chair convulsively and held on. I had a feeling

that I was holding on to the dream as well as the chair. I should not have been

surprised had the sea rushed in and drowned all that fairyland, and had I found

myself at the wheel of the Snark just looking up casually from the study

of logarithms. But the dream persisted. I looked covertly at the Madonna and

her husband. They evidenced no perturbation. The dishes had not moved upon the

table. The hibiscus and trees and grass were still there. Nothing had

changed.

"Will you have some iced tea?" asked

the Madonna; and then her side of the table sank down gently and I said yes to

her at an angle of forty-five degrees.

So the luncheon went on, and I was glad that I

did not have to bear the affliction of watching Charmian walk. Suddenly,

however, a mysterious word of fear broke from the lips of the lotus-eaters.

"Ah, ha!" thought I, "now the dream goes glimmering." I

clutched the chair desperately, resolved to drag back to the reality of the

Snark some tangible vestige of this lotus land. Just then the mysterious

word of fear was repeated. It sounded like Reporters. I looked, and saw

three of them coming across the lawn. O blessed reporters! Then the dream was

indisputable real, after all. I glanced out across the shining water and saw

the Snark at anchor, and I remembered that I had sailed in her from San

Francisco to Hawaii, and that this was Pearl Harbor, and that even then I was

saying, in reply to the first question, "Yes, we had delightful weather

all the way down."

From the August 8, 1908 issue of Harper's Weekly magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.