Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() ITH the

last morsel of bread Tom King wiped his plate clean of the last particle of

flour gravy and chewed the resulting mouthful in a slow and meditative way.

When he arose from the table he was oppressed by the feeling that he was

distinctly hungry. Yet he alone had eaten. The two children in the other room

had been sent early to bed in order that in sleep they might forget they had

gone supperless. His wife had touched nothing, and had sat silently and watched

him with solicitous eyes. She was a thin, worn woman of the working class,

though signs of an earlier prettiness were not wanting in here face. The flour

for the gravy she had borrowed from the neighbor across the hall. The last two

ha'pennies had gone to buy the bread.

ITH the

last morsel of bread Tom King wiped his plate clean of the last particle of

flour gravy and chewed the resulting mouthful in a slow and meditative way.

When he arose from the table he was oppressed by the feeling that he was

distinctly hungry. Yet he alone had eaten. The two children in the other room

had been sent early to bed in order that in sleep they might forget they had

gone supperless. His wife had touched nothing, and had sat silently and watched

him with solicitous eyes. She was a thin, worn woman of the working class,

though signs of an earlier prettiness were not wanting in here face. The flour

for the gravy she had borrowed from the neighbor across the hall. The last two

ha'pennies had gone to buy the bread.

He sat down by the window on a rickety chair that

protested under his weight, and quite mechanically he put his pipe in his mouth

and dipped into the side pocket of his coat. The absence of any tobacco made

him aware of his action and, with a scowl for his forgetfulness, he put the

pipe away. His movements were slow, almost hulking, as though he were burdened

by the heavy weight of his muscles. He was a solid-bodied, stolid-looking man,

and his appearance did not suffer from being overprepossessing. His rough

clothes were old and slouchy. The uppers of his shoes were too weak to carry

the heavy resoling that was itself of no recent date. And his cotton shirt, a

cheap, two-shilling affair, showed a frayed collar and ineradicable paint

stains.

But it was Tom King's face that advertised him

unmistakably for what it was. It was the face of a typical prizefighter; of one

who had put in long years of service in the squared ring, by that means,

developed and emphasized all the marks of the fighting beast. It was distinctly

a lowering countenance, and, that no feature of it might escape notice, it was

clean-shaven. The lips were shapeless and constituted a mouth harsh to excess,

that was like a gash in his face. The jaw was aggressive, brutal, heavy. The

eyes, slow of movement and heavy-lidded, were almost expressionless under the

shaggy, indrawn brows. Sheer animal that he was, the eyes were the most

animal-like feature about him. They were sleepy, lion-like—the eyes of a

fighting animal. The forehead slanted quickly back to the hair, which clipped

close, showed every bump of the villainous-looking head. A nose, twice broken

and moulded variously by countless blows, and a cauliflower ear, permanently

swollen and distorted to twice its size, completed his adornment, while the

beard, fresh-shaven as it was, sprouted in the skin and gave the face a

blue-black stain.

Altogether, it was the face of a man to be afraid

of in a dark alley or lonely place. And yet Tom King was not a criminal, nor

had he ever done anything criminal. Outside of brawls, common to his walk in

life, he had harmed no one. Nor had he ever been known to pick a quarrel. He

was a professional, and all the fighting brutishness of him was reserved for

his professional appearances. Outside the ring he was slow-going, easy-natured,

and, in his younger days when money was flush, too open-handed for his own

good. He bore no grudges and had few enemies. Fighting was a business with him.

In the ring he struck to hurt, struck to maim, struck to destroy; but there was

no animus in it. It was a plain business proposition. Audiences assembled and

paid for the spectacle of men knocking each other out. The winner took the big

end of the purse. When Tom King faced the Woolloomoolloo Gouger, twenty years

before, he knew that Gouger's jaw was only four months healed after having been

broken in a Newcastle bout. And he played for that jaw and broken it again in

the ninth round, not because he bore the Gouger any ill will, but because that

was the surest way to put the Gouger out and win the big end of the purse. Nor

had the Gouger borne him any ill will for it. It was the game, and both knew

the game and played it.

Tom King had never been a talker, and he sat by

the window, morosely silent, staring at his hands. The veins stood out on the

backs of the hands, large and swollen; and the knuckles, smashed and battered

and malformed, testified to the use to which they had been put. He had never

heard that a man's life was the life of his arteries, but well he knew the

meaning of those big, upstanding veins. His heart had pumped too much blood

through them at top pressure. They no longer did the work. He had stretched the

elasticity out of them, and with their distention had passed his endurance. He

tired easily now. No longer could he do a fast twenty rounds, hammer and tongs,

fight, fight, fight, from gong to gong, with fierce rally on top of fierce

rally, beaten to the ropes and in turn beating his opponent to the ropes, and

rallying fiercest and fastest of all in that last, twentieth round, with the

house on its feet and yelling, himself rushing, striking, ducking, raining

showers of blows upon showers of blows and receiving showers of blows in

return, and all the time the heart faithfully pumping the surging blood through

the adequate veins. The veins, swollen at the time, had always shrunk down

again, though not quite—neach time, imperceptibly at first, remaining just a

trifle larger than before. He stared at them and at his battered knuckles, and,

for the moment, caught a vision of the youthful excellence of those hands

before the first knuckle had been smashed on the head of Benny Jones, otherwise

known as the Welsh Terror.

The impression of his hunger came back on

him.

"Blimey, but couldn't I go a piece of

steak!" he muttered aloud, clenching his huge fists and spitting out a

smothered oath.

"I tried both Burke's an' Sawley's,"

his wife said half apologetically.

"An' they wouldn't?" he demanded.

"Not a ha'penny. Burke said ——" She

faltered.

"G'wan! Wot 'd he say?"

"As how 'e was thinkin' Sandel ud do ye

tonight, an' as how yer score was comfortable big as it was."

Tom King grunted, but did not reply. He was busy

thinking of the bull terrier he had kept in his younger days to which he had

fed steaks without end. Burke would have given him credit for a thousand

steaks—then. But times had changed. Tom King was getting old; and old men,

fighting before second-rate clubs, couldn't expect to run bills of any size

with the tradesmen.

He got up in the morning with a longing for a

piece of steak, and the longing had not abated. He had not had a fair training

for this fight. It was a drought year in Australia, times were hard and even

the most irregular work was difficult to find. He had had no sparring partner

and his food had not been of the best nor always sufficient. He had done a few

days' navvy work when he could get it, and he had run around the Domain in the

early mornings to get his legs in shape. But it was hard training without a

partner and with a wife and two kiddies that must be fed. Credit with the

tradesmen had undergone very slight expansion when he was matched with Sandel.

The secretary of the Gayety Club had advanced him three pounds—the loser's end

of the purse—and beyond that had refused to go. Now and again he had managed

to borrow a few shillings from old pals, who would have leant more only that it

was a drought year and they were hard put themselves. No—and there was no use

in disguising the fact—his training had not been satisfactory. He should have

had better food and no worries. Besides, when a man is forty it is harder to

get into condition than when he is twenty.

"What time is it, Lizzie?" he

asked.

His wife went across the hall to inquire and came

back. "Quarter before eight."

"They'll be startin' the first bout in a few

minutes," he said. "Only a try-out. Then there's a four-round spar

'tween Dealer Wells an' Gridley, an' a ten-round go 'tween Starlight an' some

sailor bloke. I don't come on for over an hour."

At the end of another silent ten minutes he rose

to his feet.

"Truth is, Lizzie, I ain't had proper

trainin'."

He reached for his hat and started for the door.

He did not offer to kiss her—he never did on going out—but on this night she

dared to kiss him, throwing her arms around him and compelling him to bend down

to her face. She looked quite small against the massive bulk of the man.

"Good luck, Tom," she said. "You

gotter do 'im."

"Ay, I gotter do 'im," he repeated.

"That's all there is to it. I jus' gotter do 'im."

He laughed with an attempt at heartiness, while

she pressed more closely against him. Across her shoulders he looked around the

bare room. It was all he had in the world, with the rent overdue, and her and

the kiddies. And he was leaving it to go out into the night to get meat for his

mate and cubs—not like a modern workingman doing to his machine grind, but in

the old, primitive, royal, animal way, by fighting for it.

"I gotter do 'im," he repeated, this

time a hint of desperation in his voice. "If it's a win it's thirty

quid—an' I can pay all that's owin', with a lump o' money left over. If it's a

lose I get naught—not even a penny for me to ride home on the tram. The

secretary's give all that's comin' from a loser's end. Good-by, old woman. I'll

come straight home if it's a win."

"An' I'll be waitin' up," she called to

him along the hall.

It was a full two miles to the Gayety, and as he

walked along he remembered how in his palmy days—he had once been the

heavyweight champion of New South Wales—he would have ridden in a cab to the

fight, and how, most likely, some heavy backer would have paid for the cab and

ridden with him. There were Tommy Burns and that Yankee n----r, Jack

Johnson—they rode about in motor cars. And he walked! And, as any man knew, a

hard two miles was not the best preliminary to a fight. He was an old un, and

the world did not wag well with old uns. He was good for nothing now except

navvy work, and his broken nose and swollen ear were against him even in that.

He found himself wishing that he had learned a trade. It would have been better

in the long run. But no one had told him, and he knew, deep down in his heart,

that he would not have listened if they had. It had been so easy. Big

money—sharp, glorious fights—periods of rest and loafing in between—a

following of eager flatterers, the slaps on the back, the shakes of the hand,

the toffs glad to buy him a drink for the privilege of five minutes' talk—and

the glory of it, the yelling houses, the whirlwind finish, the referee's

"King wins!" and his name in the sporting columns next day.

Those had been times! But he realized now, in his

slow, ruminating way, that it was the old uns he had been putting away. He was

Youth, rising; and they were Age, sinking. No wonder it had been easy—they

with their swollen veins and battered knuckles and weary in the bones of them

from the long battles they had already fought. He remembered the time he put

out old Stowsher Bill, at Rush-Cutters Bay, in the eighteenth round, and how

old Bill had cried afterward in the dressing-room like a baby. Perhaps old

Bill's rent had been overdue. Perhaps he'd had at home a missus an' a couple of

kiddies. And perhaps Bill, that very day of the fight, had had a hungering for

a piece of steak. Bill had fought game and taken incredible punishment. He

could see now, after he had gone through the mill himself, that Stowsher Bill

had fought for a bigger stake, that night twenty years ago, than had young Tom

King, who had fought for glory and easy money. No wonder Stowsher Bill had

cried afterward in the dressing-room.

Well, a man had only so many fights in him, to

begin with. It was the iron law of the game. One man might have a hundred hard

fights in him, another man only twenty; each, according to the make of him and

the quality of his fiber, had a definite number, and when he had fought them he

was done. Yes, he had had more fights in him than most of them, and he had had

far more than his share of the hard, grueling fights—the kind that worked the

heart and lungs to bursting, that took the elastic out of the arteries and made

hard knots of muscle out of youth's sleek suppleness, that wore out nerve and

stamina and made brain and bones weary from excess of effort and endurance

overwrought. Yes, he had done better than all of them. There was none of his

old fighting partners left. He was the last of the old guard. He had seen them

all finished, and he had had a hand in finishing some of them.

They had tried him out against the old uns, and

one after another he had put them away—laughing when, like old Stowsher Bill,

they cried in the dressing-room. And now he was an old un, and they tried out

the youngsters on him. There was the bloke, Sandel. He had come over from New

Zealand with a record behind him. But nobody in Australia knew anything about

him, so they put him up against old Tom King. If Sandel made a showing he would

be given better men to fight, with bigger purses to win; so it was to be

depended upon that he would put up a fierce battle. He had everything to win by

it—money and glory and career; and Tom King was the grizzled old

chopping-block that guarded the highway to fame and fortune. And he had nothing

to win except thirty quid, to pay to the landlord and the tradesmen. And, as

Tom King thus ruminated, there came to his stolid vision the form of Youth,

glorious Youth, rising exultant and invincible, supple of muscle and silken of

skin, with heart and lungs that had never been tired and torn and that laughed

at limitation of effort. Yes, Youth was the Nemesis. It destroyed the old uns

and recked not that, in so doing, it destroyed itself. It enlarged its arteries

and smashed its knuckles, and was in turn destroyed by Youth. For Youth was

ever youthful. It was only Age that grew older.

At Castlereagh Street he turned to the left, and

three blocks along came to the Gayety. A crowd of young larrikins hanging

outside the door made respectful way for him, and he heard one say to another:

"That's 'im! That's Tom King!"

"How are you feelin', Tom?" he

asked.

"Fit as a fiddle," King answered,

although he knew that he lied, and that if he had a quid he would give it right

there for a good piece of steak.

When he emerged from the dressing-room, his

seconds behind him, and came down the aisle to the squared ring in the center

of the hall, a burst of greeting and applause went up from the waiting crowd.

He acknowledged salutations right and left, though few of the faces did he

know. Most of them were the faces of kiddies unborn when he was winning his

first laurels in the squared ring. He leaped lightly to the raised platform and

ducked through the ropes to his corner, where he sat down on a folding stool.

Jack Ball, the referee, came over and shook his hand. Ball was a broken-down

pugilist who for over ten years had not entered the ring as a principal. King

was glad that he had him for referee. They were both old uns. If he should

rough it with Sandel a bit beyond the rules he knew Ball could be depended upon

to pass it by.

Aspiring young heavyweights, one after another,

were climbing into the ring and being presented to the audience by the referee.

Also, he issued their challenges for them.

"Young Pronto," Ball announced,

"from North Sydney, challenges the winner for fifty pounds side

bet."

The audience applauded, and applauded again as

Sandel himself sprang through the ropes and sat down in his corner. Tom King

looked across the ring at him curiously, for in a few minutes they would be

locked together in merciless combat, each trying with all the force of him to

knock the other into unconsciousness. But little could he see, for Sandel, like

himself, had trousers and sweater on over his ring costume. His face was

strongly handsome, crowned with a curly mop of yellow hair, while his thick

muscular neck hinted at bodily magnificence.

Young Pronto went to one corner and then the

other, shaking hands with the principals and dropping down out of the ring. The

challenges went on. Ever Youth climbed through the ropes—Youth unknown, but

insatiable—crying out to mankind that with strength and skill it would match

issues with the winner. A few years before, in his own heyday of

invincibleness, Tom King would have been amused and bored by these

preliminaries. But now he sat fascinated, unable to shake the vision of Youth

from his eyes. Always were these youngsters rising up in the boxing game,

springing through the ropes and shouting their defiance; and always were the

old uns going down before them. They climbed to success over the bodies of the

old uns. And ever they came, more and more youngsters—Youth unquenchable and

irresistible—and ever they put the old uns away, themselves becoming old uns

and traveling the same downward path, while behind them, ever pressing on them,

was Youth eternal—the new babies, grown lusty and dragging their elders down,

with behind them more babies to the end of time—Youth that must have its will

and that will never die.

King glanced over to the press box and nodded to

Morgan, of the Sportsman, and Corbett, of the Referee. Then he held out his

hands, while Sid Sullivan and Charley Bates, his seconds slipped on his gloves

and laced them tight, closely watched by one of Sandel's seconds, who first

examined critically the tapes on King's knuckles. A second of his own was in

Sandel's corner, performing a like office. Sandel's trousers were pulled off

and, as he stood up, his sweater was skinned over his head. And Tom King,

looking, saw Youth incarnate, deep-chested, heavy-thewed, with muscles that

slipped and slid like live things under the white satin skin. The whole body

was acrawl with life, and Tom King knew that it was a life that had never oozed

its freshness out though the aching pores during the long fights wherein Youth

paid its toll and departed not quite so young as when it entered.

The two men advanced to meet each other and, as

the gong sounded and the seconds clattered out of the ring with the folding

stools, they shook hands with each other and instantly took their fighting

attitudes. And instantly, like a mechanism of steel and springs balanced on a

hair trigger, Sandel was in and out and in again, landing a left to the eyes, a

right to the ribs, ducking a counter, dancing lightly away and dancing

menacingly back again. He was swift and clever. It was a dazzling exhibition.

The house yelled its approbation. But King was not dazzled. He had fought too

many fights and too many youngsters. He knew the blows for what they were—too

quick and too deft to be dangerous. Evidently Sandel was going to rush things

from the start. It was to be expected. It was the way of Youth, expending its

splendor and excellence in wild insurgence and furious onslaught, overwhelming

opposition with its own unlimited glory of strength and desire.

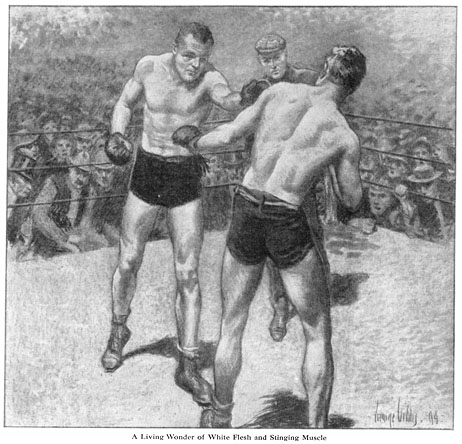

Sandel was in and out, here, there and

everywhere, light-footed and eager-hearted, a living wonder of white flesh and

stinging muscle that wove itself into a dazzling fabric of attack, slipping and

leaping like a flying shuttle from action to action through a thousand actions,

all of them centered upon the destruction of Tom King, who stood between him

and fortune. And Tom King patiently endured. He knew his business, and he knew

Youth now that Youth was no longer his. There was nothing to do till the other

lost some of his steam, was his thought, and he grinned to himself as he

deliberately ducked so as to receive a heavy blow on the top of his head. It

was a wicked thing to do, yet eminently fair according to the rules of the

boxing game. A man was supposed to take care of his own knuckles, and if he

insisted on hitting an opponent on the top of the head he did so at his own

peril. King could have ducked lower and let the blow whiz harmlessly past, but

he remembered his own early fights and how he smashed his first knuckle on the

head of the Welsh Terror. He was but playing the game. That duck had accounted

for one of Sandel's knuckles. Not that Sandel would mind it now. He would go

on, superbly regardless, hitting as hard as ever throughout the fight. But

later on, when the long ring battles had begun to tell, he would regret that

knuckle and look back and remember how he smashed it on Tom King's head.

The first round was all Sandel's, and he had the

house yelling with the rapidity of his whirlwind rushes. He overwhelmed King

with avalanches of punches, and Kind did nothing. He never struck once,

contenting himself with covering up, blocking and ducking and clinching to

avoid punishment. He occasionally feinted, shook his head when the weight of a

punch landed, and moved stolidly about, never leaping or springing or wasting

an ounce of strength. Sandel must foam the froth of Youth away before discreet

Age could dare to retaliate. All King's movements were slow and methodical, and

his heavy-lidded, slow-moving eyes gave him the appearance of being half asleep

or dazed. Yet they were eyes that saw everything, that had been trained to see

everything thought all his twenty years and odd in the ring. They did not blink

or waver before an impending blow, but that coolly saw and measured

distance.

Seated in his corner for the minute's rest at the

end of the round, he lay back with outstretched legs, his arms resting on the

right angle of the ropes, his chest and abdomen heaving frankly and deeply as

he gulped down the air driven by the towels of his seconds. He listened with

closed eyes to the voices of the house. "Why don't yeh fight, Tom?"

many were crying. "Yeh ain't afraid of 'im, are yeh?"

"Muscle-bound," he heard a man on a

front seat comment. "He can't move quicker. Two to one on Sandel, in

quids."

The gong struck and the two men advanced from

their corners. Sandel came forward fully three-quarters of the distance, eager

to begin again; but King was content to advance the shorter distance. It was in

line with his policy of economy. He had not been well trained and he had not

had enough to eat, and every step counted. Besides, he had already walked two

miles to the ringside. It was a repetition of the first round, with Sandel

attacking like a whirlwind and with the audience indignantly demanding why King

did not fight. Beyond feinting and several slowly-delivered and ineffectual

blows he did nothing save block and stall and clinch. Sandel wanted to make the

pace fast, while King, out of his wisdom, refused to accommodate him. He

grinned with a certain wistful pathos in his ring-battered countenance, and

went on cherishing his strength with the jealousy of which only Age is capable.

Sandel was Youth, and he threw his strength away with the munificent abandon of

Youth. To King belonged the ring generalship, the wisdom bred of long, aching

fights. He watched with cool eyes and head, moving slowly and waiting for

Sandel's froth to foam away. To the majority of the onlookers it seemed as

though King was hopelessly outclassed, and they voiced their opinion in offers

of three to one on Sandel. But there were wise ones, a few, who knew King of

old time and who covered what they considered easy money.

The third round began as usual, one-sided, with

Sandel doing all the leading and delivering all the punishment. A half-minute

has passed when Sandel, overconfident, left an opening. King's eyes and right

arm flashed in the same instant. It was his first real blow—a hook, with the

twisted arch of the arm to make it rigid, and with all the weight of the

half-pivoted body behind it. It was like a sleepy-seeming lion suddenly

thrusting out a lightning paw. Sandel, caught on the side of the jaw, was

felled like a bullock. The audience gasped and murmured awe-stricken applause.

The man was not muscle-bound, after all, and he could drive a blow like a

triphammer.

Sandel was shaken. He rolled over and attempted

to rise, but the sharp yells form his seconds to take the count restrained him.

He knelt on one knee, ready to rise, and waited, while the referee stood over

him, counting the seconds loudly in his ear. At the ninth he rose in fighting

attitude, and Tom King, facing him, knew regret that the blow had not been an

inch nearer the point of the jaw. That would have been a knockout, and he could

have carried the thirty quid home to the missus and the kiddies.

The round continued to the end of its three

minutes, Sandel for the first time respectful of his opponent and King slow of

movement and sleepy-eyed as ever. As the round neared its close King, warned of

the fact by sight of the seconds crouching outside ready of the spring in

through the ropes, worked the fight around to his own corner. And when the gong

struck he sat down immediately on the waiting stool, while Sandel had to walk

all the way across the diagonal of the square to his own corner. It was a

little thing, but it was the sum of little things that counted. Sandel was

compelled to walk that many more steps, to give up that much energy and to lose

a part of the precious minute of rest. At the beginning of every round King

loafed slowly out from his corner, forcing his opponent to advance the greater

distance. The end of every round the fight manœuvered by King into his

own corner so that he could immediately sit down.

Two more rounds went by, in which King was

parsimonious of effort and Sandel prodigal. The latter's attempt to force a

fast pace made King uncomfortable, for a fair percentage of the multitudinous

blows showered upon him went home. Yet King persisted in his dogged slowness,

despite the crying of the younger hotheads for him to go in and fight. Again,

in the sixth round, Sandel was careless, again Tom King's fearful right flashed

out to the jaw, and again Sandel took the nine seconds' count.

By the seventh round Sandel's pink of condition

was gone and he settled down to what he knew was to be the hardest fight in his

experience. Tom King was an old un, but a better old un than he had ever

encountered—an old un who never lost his head, who was remarkably able at

defense, whose blows had the impact of a knotted club and who had a knockout in

either hand. Nevertheless, Tom King dared not hit often. He never forgot his

battered knuckles, and knew that every hit must count if the knuckles were to

last out the fight. As he sat in his corner, glancing across at his opponent,

the thought came to him that the sum of his wisdom and Sandel's youth would

constitute a world's champion heavyweight. But that was the trouble. Sandel

would never become a world champion. He lacked the wisdom, and the only way for

him to get it was to buy it with Youth; and when wisdom was his, Youth would

have been spent in buying it.

King took every advantage he knew. He never

missed an opportunity to clinch, and in effecting most of the clinches his

shoulder drove stiffly into the other's ribs. In the philosophy of the ring a

shoulder was as good as a punch so far as damage was concerned, and a great

deal better so far as concerned expenditure of effort. Also, in the clinches

King rested his weight on his opponent and was loth to let go. This compelled

the interference of the referee, who tore them apart, always assisted by

Sandel, who had not yet learned to rest. He could not refrain from using those

glorious flying arms and writhing muscles of his, and when the other rushed

into a clinch, striking shoulder against ribs and with head resting under

Sandel's left arm, Sandel almost invariably swung his right behind his own back

and into the projecting face. It was a clever stroke, much admired by the

audience, but it was not dangerous, and was, therefore, just that much wasted

strength. But Sandel was tireless and unaware of limitations, and King grinned

and doggedly endured.

Sandel developed a fierce right to the body,

which made it appear that King was taking an enormous amount of punishment, and

it was only the old ringsters who appreciated the deft touch of King's left

glove to the other's biceps just before the impact of the blow. It was true,

the blow landed each time; but each time it was robbed of its power by that

touch on the biceps. In the ninth round, three times inside a minute, King's

right hooked its twisted arch to the jaw; and three times Sandel's body, heavy

as it was, was leveled to the mat. Each time he took the nine seconds allowed

him and rose to his feet, shaken and jarred, but still strong. He had lost much

of his speed and he wasted less effort. He was fighting grimly; but he

continued to draw upon his chief asset, which was Youth. King's chief asset was

experience. As his vitality had dimmed and his vigor abated he had replaced

them with cunning, with wisdom born of the long fights and with a careful

shepherding of strength. Not alone had he learned never to make a superfluous

movement, but he had learned how to seduce an opponent into throwing his

strength away. Again and again, by feint of foot and hand and body he continued

to inveigle Sandel into leaping back, ducking or countering. King rested, but

he never permitted Sandel to rest. It was the strategy of Age.

Early in the tenth round King began stopping the

other's rushes with straight left to the face, and Sandel, grown wary,

responded by drawing the left, then by ducking it and delivering his right in a

sweeping hook to the side of the head. It was too high up to be vitally

effective; but when first it landed King knew the old, familiar descent of the

black veil of unconsciousness across his mind. For the instant, or for the

slightest fraction of an instant rather, he ceased. In the one moment he saw

his opponent ducking out of his field of vision and the background of white,

watching faces; in the next moment he again saw his opponent and the background

of faces. It was if he had slept for a time and just opened his eyes again, and

yet the interval of unconsciousness was so microscopically short that there had

been no time for him to fall. The audience saw him totter and his knees give,

and then saw him recover and tuck his chin deeper into the shelter of his left

shoulder.

Several times Sandel repeated the blow, keeping

King partially dazed, and then the latter worked out his defense, which was

also a counter. Feinting with his left he took a half-step backward, at the

same time uppercutting with the whole strength of his right. So accurate was it

timed that it landed squarely on Sandel's face in the full, downward sweep of

the duck, and Sandel lifted in the air and curled backward, striking the mat on

his head and shoulders. Twice King achieved this, then turned loose and

hammered his opponent to the ropes. He gave Sandel no chance to rest or to set

himself, but smashed blow in upon blow till the house rose to its feet and the

air was filled with an unbroken roar of applause. But Sandel's strength and

endurance were superb, and he continued to stay on his feet. A knockout seemed

certain, and a captain of police, appalled at the dreadful punishment, arose by

the ringside to stop the fight. The gong struck for the end of the round and

Sandel staggered to his corner, protesting to the captain that he was sound and

strong. To prove it he threw two back air springs, and the police captain gave

in.

Tom King, leaning back in his corner and

breathing hard, was disappointed. If the fight had been stopped the referee,

perforce, would have rendered him the decision and the purse would have been

his. Unlike Sandel, he was not fighting for glory or career, but for thirty

quid. And now Sandel would recuperate in the minute of rest.

Youth will be served—this saying flashed into

King's mind, and he remembered the first time he had heard it, the night when

he had put away Stowsher Bill. The toff who had bought him a drink after the

fight and patted him on the shoulder had used those words. Youth will be

served! The toff was right. And on that night in the long ago he had been

Youth. Tonight Youth sat in the opposite corner. As for himself, he had been

fighting for half an hour now, and he was an old man. Had he fought like Sandel

he would not have lasted fifteen minutes. But the point was that he did not

recuperate. Those upstanding arteries and that sorely-tried heart would not

enable him to gather strength in the intervals between the rounds. And he had

not sufficient strength in him to begin with. His legs were heavy under him and

beginning to cramp. He should not have walked those two miles to the fight. And

there was the steak which he had got up longing for that morning. A great and

terrible hatred rose up in him for the butchers who had refused him credit. It

was hard for an old man to go into a fight without enough to eat. And a piece

of steak was such a little thing, a few pennies at best; yet it meant thirty

quid to him.

With the gong that opened the eleventh round

Sandel rushed, making a show of freshness which he did not really possess. King

knew it for what it was—a bluff as old as the game itself. He clinched to save

himself, when, going free, allowed Sandel to get set. This was what King

desired. He feinted with his left, drew the answering duck and swinging upward

hook, then made the half-step backward, delivered the uppercut full to the face

and crumpled Sandel over to the mat. After that he never let him rest,

receiving punishment himself, but inflicting far more, smashing Sandel to the

ropes, hooking and driving all manner of blows into him, tearing away from his

clinches or punching him out of attempted clinches, and ever, when Sandel would

have fallen, catching him with one uplifting hand and with the other

immediately smashing him into the ropes where he could not fall.

The house by this time had gone mad, and it was

his house, nearly every voice yelling; "Go it, Tom!" "Get 'im!

Get 'im!" "You've got 'im, tom! You've got 'im!" It was to be a

whirlwind finish, and that was what a ringside audience paid to see.

And Tom King, who for half an hour had conserved

his strength, now expended it prodigally in the one great effort he knew he had

in him. It was his once chance—now or not at all. His strength was waning

fast, and his hope was that before the last of it ebbed out of him he would

have beaten his opponent down for the count. And as he continued to strike and

force, cooling estimating the weight of his blows and the quality of the damage

wrought, he realized how hard a man Sandel was to knock out. Stamina and

endurance were his to an extreme degree, and they were the virgin stamina and

endurance of Youth. Sandel was certainly a coming man. He had it in him. Only

out of such rugged fiber were successful fighters fashioned.

Sandel was reeling and staggering, but

Tom King's legs were cramping and his knuckles going back on him. Yet he

steeled himself to strike the fierce blows, every one of which brought anguish

to his tortured hands. Though now he was receiving practically no punishment he

was weakening as rapidly as the other. His blows went home, but there was no

longer the weight behind them, and each blow was the result of a severe effort

of will. His legs were like lead, and they dragged visibly under him; while

Sandel's backers, cheered by this symptom, began calling encouragement to their

man.

Sandel was reeling and staggering, but

Tom King's legs were cramping and his knuckles going back on him. Yet he

steeled himself to strike the fierce blows, every one of which brought anguish

to his tortured hands. Though now he was receiving practically no punishment he

was weakening as rapidly as the other. His blows went home, but there was no

longer the weight behind them, and each blow was the result of a severe effort

of will. His legs were like lead, and they dragged visibly under him; while

Sandel's backers, cheered by this symptom, began calling encouragement to their

man.

King was spurred to a burst of effort. He

delivered two blows in succession—a left, a trifle too high, to the solar

plexus, and a right cross to the jaw. They were not heavy blows, yet so weak

and dazed was Sandel that he went down and lay quivering. The referee stood

over him, shouting the count of the fatal seconds in his ear. If before the

tenth second was called he did not rise the fight was lost. The house stood in

hushed silence. King rested on trembling legs. A mortal dizziness was upon him,

and before his eyes the sea of faces sagged and swayed, while to his ears, as

from a remote distance, came the count of the referee. Yet he looked upon the

fight as his. It was impossible that a man so punished could rise.

Only Youth could rise, and Sandel rose. At the

fourth second he rolled over on his face and groped blindly for the ropes. By

the seventh second he had dragged himself to his knee, where he rested, his

head rolling groggily on his shoulders. As the referee cried "Nine!"

Sandel stood upright, in proper stalling position, his left arm wrapped about

his face, his right wrapped about his stomach. Thus were his vital points

guarded, while he lurched forward toward King in the hope of effecting a clinch

and gaining more time.

At the instant Sandel arose King was at him, but

the two blows he delivered were muffled on the stalled arms. The next moment

Sandel was in the clinch and holding on desperately while the referee strove to

drag the two men apart. King helped to force himself free. He knew the rapidity

with which Youth recovered and he knew that Sandel was his if he could prevent

that recovery. One stiff punch would do it. Sandel was his, indubitably his. He

had outgeneraled him, outfought him, outpointed him. Sandel reeled out of the

clinch, balanced on the hairline between defeat or survival. One good blow

would topple him over and down and out. And Tom King, in a flash of bitterness,

remembered the piece of steak and wished that he had it then behind that

necessary punch he must deliver. He nerved himself for the blow, but it was not

heavy enough nor swift enough. Sandel swayed but did not fall, staggering back

to the ropes and holding on. King staggered after him and, with a pang like

that of dissolution, delivered another blow. But his body had deserted him. All

that was left of him was a fighting intelligence that was dimmed and clouded

from exhaustion. The blow that was aimed for the jaw struck no higher than the

shoulder. He had willed the blow higher, but the tired muscles had not been

able to obey. And from the impact of the blow Tom King himself reeled back and

nearly fell. Once again he strove. This time his punch missed altogether, and,

from absolute weakness, he fell against Sandel and clinched, holding on to him

to save himself from sinking to the floor.

King did not attempt to free himself. He had shot

his bolt. He was gone. And Youth had been served. Even in the clinch he could

feel Sandel growing stronger against him. When the referee thrust them apart,

there, before his eyes, he saw Youth recuperate. From instant to instant Sandel

grew stronger. His punches, weak and futile at first, became stiff and

accurate. Tom King's bleared eyes saw the gloved fist driving at his jaw and he

willed to guard it by interposing his arm. He saw the danger, willed the act;

but the arm was too heavy. It seemed burdened with a hundredweight of lead. It

would not lift itself, and he strove to lift it with his soul. Then the gloved

fist landed home. He experienced a sharp snap that was like an electric spark

and, simultaneously, the veil of blackness enveloped him.

When he opened his eyes again he was in his

corner, and he heard the yelling of the audience like the roar of the surf at

Bondi Beach. A wet sponge was being pressed against the base of his brain and

Sid Sullivan was blowing cold water in a refreshing spray over his face and

chest. His gloves had already been removed and Sandel, bending over him, was

shaking his hand. He bore no ill will toward the man who had put him out, and

he returned the grip with a heartiness that made his battered knuckles protest.

Then Sandel stepped to the center of the ring and the audience hushed its

pandemonium to hear him accept young Pronto's challenge and offer to increase

the side bet to one hundred pounds. King looked on apathetically while his

seconds mopped the streaming water from him, dried his face and prepared him to

leave the ring. He felt hungry. It was not the ordinary, gnawing kind, but a

great faintness, a palpitation at the pit of the stomach that communicated

itself to all his body. He remembered back into the fight to the moment when he

had Sandel swaying and tottering on the hairline balance of defeat. Ah, that

piece of steak would have done it! He had lacked just that for the decisive

blow, and he had lost. It was all because of the piece of steak.

His seconds were half-supporting him as they

helped him through the ropes. He tore free from them, ducked through the roped

unaided and leaped heavily to the floor, following on their heels as they

forced a passage for him down the crowded center aisle. Leaving the

dressing-room for the street, in the entrance to the hall, some young fellow

spoke to him.

"W'y didn't yuh go in an' get 'im when yuh

'ad 'im?" the young fellow asked.

"Aw, go to hell!" said Tom King, and

passed down the steps to the sidewalk.

The doors of the public house at the corner were

swinging wide, and he saw the lights and the smiling barmaids, heard the many

voices discussing the fight and the prosperous chink of money on the bar.

Somebody called to him to have a drink. He hesitated perceptibly, then refused

and went on his way.

He had not a copper in his pocket and the

two-mile walk home seemed very long. He was certainly getting old. Crossing the

Domain he sat down suddenly on a bench, unnerved by the thought of the missus

sitting up for him, waiting to learn the outcome of the fight. That was harder

than any knockout, and it seemed almost impossible to face.

He felt weak and sore, and the pain of his

smashed knuckles warned him that, even if he could find a job at navvy work, it

would be a week before he could grip a pick handle or a shovel. The hunger

palpitation at the pit of the stomach was sickening. His wretchedness

overwhelmed him, and into his eyes came an unwonted moisture. He covered his

face with his hands and, as he cried, he remembered Stowsher Bill and how he

had served him that night in the long ago. Poor old Stowsher Bill! He could

understand now why Bill had cried in the dressing-room.

From the November 20, 1909 issue of The Saturday Evening Post magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.