Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]() HIS

is a story of things that happened, which goes to show that there is an eternal

core of goodness in the hearts of all men. Bertram Cornell was a bad man, and a

failure. In a little English home overseas there had been sorrow unavailing and

tears shed in vain for his earthly and spiritual welfare. He was bad, utterly

bad. There could be no doubt of it. Thoughtless, careless and uncaring were

mild terms with which to brand his weaknesses.

HIS

is a story of things that happened, which goes to show that there is an eternal

core of goodness in the hearts of all men. Bertram Cornell was a bad man, and a

failure. In a little English home overseas there had been sorrow unavailing and

tears shed in vain for his earthly and spiritual welfare. He was bad, utterly

bad. There could be no doubt of it. Thoughtless, careless and uncaring were

mild terms with which to brand his weaknesses.

Even in his boyhood he had been strong only for

evil. Kind words and pleadings had no effect on him, and he had been callous to

the wet eyes of his mother and sisters and the sterner though no less kindly

admonitions of his father. So it could hardly have been otherwise, when yet a

very young man, that he fled hurriedly out of his home in England, carrying

with him something which should have burdened his conscience had he but

possessed one, and leaving behind a disgrace on his name for his people to

bear. And so it was that those who had known him spoke of him in bitterness and

sadness, until the memory of him was dimmed with time. Of what further evils

he wrought there was never a whisper, and of his end no one ever heard. In his

last hour he made recompense and wiped clean his tarnished page of life. But he

did this thing in a far country, where news travels slowly and gets lost upon

the way, and where men ofttimes die before they can tell how others died. But

this was the way of it. Strong of body and uncaring, he had laughed at the

great rough hand of the world and had always done, not what the world demanded,

but whatever Bertram Cornell desired. And he had met harsh words with harsher,

and stout blows with stouter. He had served as sailor on many seas, as

sheepherder on the Australian ranges, as cowboy among the Dakota cattlemen, and

as an enrolled private with the Mounted Police of the Northwest Territory. From

this last post he had deserted on the discovery of gold in the Klondike and

worked his way to the Alaskan coast. Here, because of his frontier experience,

he speedily found place to fit into in a party of three other men.

This party was bound for the Klondike, but it had

planned to abandon the beaten track and to go into the country over a new and

untraveled route. With a pack train of many horses (cayuses from the mountains

of eastern Oregon), the four men struck east into the desolate wilderness which

lies beyond Mount St. Elias, and then north through the upland region in which

the headwaters of the White and Tanana rivers have their source. It was an

unexplored domain, marked vaguely on the maps, which was yet to feel the foot

of the first white man. So vast and dismal was it that even animal life was

scarce, and the tiny Indian tribes few and far between. For days, sometimes,

they rode through the silent forest of by the rims of lonely lakes and saw no

living thing, heard no sound save the sighing of the wind and the sobbing of

the waters. A great solemnity brooded over the land, and the quiet was so

profound that they came to hush their voices and to waste few words in idle

talk.

![]() S they

journeyed on they prospected for the hidden gold, groping in the chill pools of

the torrents and panning dirt in the shadows of the mighty glaciers. Once they

came upon a body of virgin copper, like a mountain, but they could only shrug

their shoulders and pass on. Food for their horses was scarce, and quite often

poisonous, and the patient animals died one by one on the strange trail their

masters had led them to. Crossing a high divide, the party was overwhelmed by a

sleety storm common to such elevations, and, when finally they struggled

through to the warmer valley beneath, the last horse had been left behind.

S they

journeyed on they prospected for the hidden gold, groping in the chill pools of

the torrents and panning dirt in the shadows of the mighty glaciers. Once they

came upon a body of virgin copper, like a mountain, but they could only shrug

their shoulders and pass on. Food for their horses was scarce, and quite often

poisonous, and the patient animals died one by one on the strange trail their

masters had led them to. Crossing a high divide, the party was overwhelmed by a

sleety storm common to such elevations, and, when finally they struggled

through to the warmer valley beneath, the last horse had been left behind.

But here, in the sheltered valley, John Thornton

cleared back the moss and from the grassroots shook out glittering particles of

yellow gold. Bertram Cornell was with him at the time, and that night the twain

carried back to camp nuggets which weighed a thousand dollars in the scales. A

stop was called, and at the end of a month the four men had mined a treasure

far greater than they could carry. But their food supply had been steadily

growing less and less, till one man could bend forward and bear it all on his

back.

What with the bleak region and fall coming on, it

was high time to be going along. Somewhere to the northeast they knew the

Klondike lay and the country of the Yukon. How far they did not know, though

they thought it could not be more than a hundred miles. So each took about five

pounds of gold, or a thousand dollars, and the rest of the great treasure they

cached safely against their return. And to return they intended just as soon as

they could lay in more grub. Their ammunition having given out, they left their

rifles with the gold, burdening themselves only with the camp equipage and the

scant supply of food.

So sure were they that they would shortly reach

the gold diggings, that they ate unsparingly of the provisions; so that on the

tenth day they found but a few miserable pounds remaining. And still before

them, in up-heaved earth-waves, range upon range, towered the great grim

mountains. Then it was that doubt came, and fear settled upon the men, and Bill

Hines began to ration out the food.

![]() HEY no

longer ate at midday, and morning and evening he divided the day's allowance

into four meager portions. It was evenly shared, but it was very

little—enough to keep soul and body together, but not enough to furnish

the proper strength to healthy toiling men. Their faces grew wan and haggard,

and day by day they covered less ground. Often the nausea of emptiness seized

them, and their knees shook with weakness, and they reeled and fell. And

always, when they had gasped and dragged themselves to the crest of a jagged

mountain pass and eagerly looked beyond, another mountain confronted them. And

always the brooding peace lay heavy over the land, and there was nothing but

the loneliness and silence without end.

HEY no

longer ate at midday, and morning and evening he divided the day's allowance

into four meager portions. It was evenly shared, but it was very

little—enough to keep soul and body together, but not enough to furnish

the proper strength to healthy toiling men. Their faces grew wan and haggard,

and day by day they covered less ground. Often the nausea of emptiness seized

them, and their knees shook with weakness, and they reeled and fell. And

always, when they had gasped and dragged themselves to the crest of a jagged

mountain pass and eagerly looked beyond, another mountain confronted them. And

always the brooding peace lay heavy over the land, and there was nothing but

the loneliness and silence without end.

![]() NE by

one, they threw away their blankets and spare clothes. They dropped their axes

by the way, and the spare cooking utensils, and even the sacks of gold dust,

until at last they staggered onward, half-naked, unburdened save for the

pittance of grub that remained. This, Jan Jensen, the Dane, divided by weight

into four parts so that the burden might be equally distributed. And each man,

by the holy though unwritten and unspoken bonds of comradeship, held sacred

that which he carried on his back. The small grub-packs were never opened

except by the light of the campfire, where all could see and where just

division was made.

NE by

one, they threw away their blankets and spare clothes. They dropped their axes

by the way, and the spare cooking utensils, and even the sacks of gold dust,

until at last they staggered onward, half-naked, unburdened save for the

pittance of grub that remained. This, Jan Jensen, the Dane, divided by weight

into four parts so that the burden might be equally distributed. And each man,

by the holy though unwritten and unspoken bonds of comradeship, held sacred

that which he carried on his back. The small grub-packs were never opened

except by the light of the campfire, where all could see and where just

division was made.

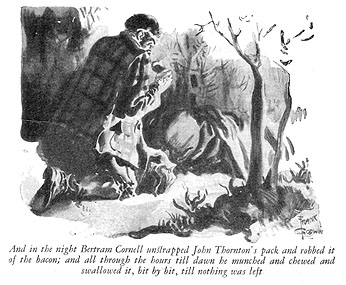

Of bacon they possessed one three-pound chunk,

which John Thornton carried in addition to a few cups of flour. This one piece

they were saving for the very last, when the need would be greatest, and they

resolutely refrained from touching it. But Bertram Cornell cast hungry eyes

upon it and thought hungry thoughts. And in the night, while his comrades slept

the sleep of exhaustion, he unstrapped John Thornton's pack and robbed it of

the bacon; and all through the hours till dawn, taking care lest the

unaccustomed quantity turn his stomach, he munched and chewed and swallowed it,

bit by bit, till nothing at all of it was left.

![]() N the

day which followed he took good care to hide the new strength which had come to

him of the night and, if anything, appeared weaker than the rest. It was a very

hard day; John Thornton lagged behind and rested often; but by nightfall they

had cleared another mountain and beheld the opening of a small river valley

beneath, running to the eastward. To the eastward! There lay the Klondike and

safety! A few more days, could they but manage to live through them, they would

be among white men and grub-caches again.

N the

day which followed he took good care to hide the new strength which had come to

him of the night and, if anything, appeared weaker than the rest. It was a very

hard day; John Thornton lagged behind and rested often; but by nightfall they

had cleared another mountain and beheld the opening of a small river valley

beneath, running to the eastward. To the eastward! There lay the Klondike and

safety! A few more days, could they but manage to live through them, they would

be among white men and grub-caches again.

But, huddled by the fire, the starving men

looking greedily on, Bill Hines opened Thornton's pack to get some flour. In an

instant each eye had noted the absence of the bacon. Thornton's eyes stared in

horror, and Hines dropped the pack and sobbed aloud. But Jan Jensen drew his

hunting knife and spoke. His voice was low and husky, almost a whisper, but

each word fell slowly from his lips, and distinctly.

"My comrades, this is murder.

This man has slept with us and shared with us in all fairness. When we divided

all the grub by weight, each man carried on his back the lives of his comrades.

And so did this man carry our lives on his back. It was a trust, a great trust,

a sacred trust. He has not been true to it. Today, when he dropped behind, we

thought he was weary. We were mistaken. Behold! He has eaten that which was

ours, upon which our very lives were hanging. There is no other name for it

than murder. For murder there is one punishment, and only one. Am I not right,

my comrades?"

"My comrades, this is murder.

This man has slept with us and shared with us in all fairness. When we divided

all the grub by weight, each man carried on his back the lives of his comrades.

And so did this man carry our lives on his back. It was a trust, a great trust,

a sacred trust. He has not been true to it. Today, when he dropped behind, we

thought he was weary. We were mistaken. Behold! He has eaten that which was

ours, upon which our very lives were hanging. There is no other name for it

than murder. For murder there is one punishment, and only one. Am I not right,

my comrades?"

"Ay!" Bill Hines cried; but Bertram

Cornell remained silent. He had not expected this.

Jan Jensen raised the long-bladed knife to

strike, but Cornell gripped his wrist. "Let me speak," he demanded.

Thornton staggered slowly to his feet and said,

"It is not right that I should die. I did not eat the bacon; nor could I

have lost it. I know nothing about it. But I swear solemnly by the most high

God that I have neither touched nor tasted the bacon!"

"If you were sneak enough to eat it,

certainly you are sneak enough to lie about it now," Jensen charged,

fingering the knife impatiently.

"Leave him alone, I tell you,"

threatened Cornell. "We don't know that he ate it. We know nothing about

it. And I warn you, I won't stand by and see murder done. There is a chance

that he is not guilty. Don't trifle with that chance. You dare not punish him

on a chance."

The angry Dane sheathed the blade, but an hour

later, when Thornton happened to speak to him, he turned his back. Bill Hines

also refused to hold conversation with the wretched man, while Cornell, already

ashamed for the good which had fluttered in him (the first in years), would

have nothing to do with him.

![]() HE

next morning Bill Hines lumped the little remaining food together and redivided

it into four parts. From Thornton's portion he subtracted the equivalent of the

bacon, which same he shared among the other three piles. This he did without a

word; the act was too significant to need speech.

HE

next morning Bill Hines lumped the little remaining food together and redivided

it into four parts. From Thornton's portion he subtracted the equivalent of the

bacon, which same he shared among the other three piles. This he did without a

word; the act was too significant to need speech.

"And let him carry his own grub,"

Jensen growled. "If he wants to eat it all at once, he's welcome

to."

What John Thornton suffered in the days which

followed, only John Thornton knows. Not only did his comrades turn from him

with abhorrent faces, but he was judged guilty of the blackest and most

cowardly of crimes—that of treason. And further, eating less than they,

he was forced to keep up with them or perish. Even then, when he had eaten his

very last pinch, they had food left for two days. So he cut the leather tops

from his moccasins and boiled them and ate them and during the day chewed the

bark of willow-shoots till the pain of his swollen and inflamed mouth nearly

drove him mad. And he dragged onward, staggering, falling, crawling, as often

in delirium as not.

But the day came when the three other men fell

back upon their moccasins and the green shoots of young trees. By this time

they had followed the torrent down until it had become a small river, and they

were counseling desperately the gathering of the drift-logs into a rickety

raft. Then it was that they came unexpectedly upon an Indian village of a dozen

lodges. But the Indians had never seen white men before and greeted them with a

shower of arrows. "See! The river! Canoes!" Jensen cried. "We're

saved if we can make them! We must make them!"

They ran, drunkenly, toward the bank,

the howling tribesmen on their heels and gaining. Suddenly, from behind a tree

to one side, a skin-clad warrior stepped forth. He poised his great

ivory-pointed spear for a moment, then cast it with perfect aim. Singing and

hurtling through the air, it drove full into John Thornton's hips. He wavered

for a second, tripped and fell forward on his face. Hines and Jensen, running

just behind him, swerved to the right and left and passed him on either side.

They ran, drunkenly, toward the bank,

the howling tribesmen on their heels and gaining. Suddenly, from behind a tree

to one side, a skin-clad warrior stepped forth. He poised his great

ivory-pointed spear for a moment, then cast it with perfect aim. Singing and

hurtling through the air, it drove full into John Thornton's hips. He wavered

for a second, tripped and fell forward on his face. Hines and Jensen, running

just behind him, swerved to the right and left and passed him on either side.

![]() HEN

the miracle came to pass. The spirit of Goodness fluttered mightily in Bertram

Cornell's breast. Without thought, obeying the inward prompting, he sprang

forward on the instant and seized the fleeing men by the arms.

HEN

the miracle came to pass. The spirit of Goodness fluttered mightily in Bertram

Cornell's breast. Without thought, obeying the inward prompting, he sprang

forward on the instant and seized the fleeing men by the arms.

"Come back!" he cried hoarsely.

"Carry Thornton to the canoes! I'll hold the Indians back until you shove

clear!"

"Leave go!" the Dane screamed, fumbling

for his knife. "I wouldn't touch the dog to save my life!"

"I stole the bacon. I ate the bacon. Now

will you come back?" Cornell saw the doubt in their eyes. "As I hope

for mercy at the Judgment Seat, I stole it." A flight of arrows fell about

them like rain. "Hurry! I'll hold them back!"

In a trice they were staggering toward the canoes

with the wounded man between them; but Bertram Cornell faced about and stood

still. Surprised by this action, the Indians hesitated and halted, while

Cornell, seeing that it was gaining time, made no motion. They discharged a

shower of arrows at him. The bone-barbed missiles flew about him like hail.

Half a dozen arrows entered his chest and legs,

and one pinned into his neck. But he yet stood upright and still as a carved

statue. The warrior who flung the spear at Thornton approached him from the

side, and they closed together in each other's arms. At this the rest of the

tribesmen came down upon him in a flood of war.

![]() S they

cut and hacked, he heard Jan Jensen shouting from the water, and he knew that

his comrades were safe. Then he fought the good fight, the first for a good

cause in all his life, and the last. But when all was still, the Indians drew

back in superstitious awe. With him lay their chief and six of their

fellows.

S they

cut and hacked, he heard Jan Jensen shouting from the water, and he knew that

his comrades were safe. Then he fought the good fight, the first for a good

cause in all his life, and the last. But when all was still, the Indians drew

back in superstitious awe. With him lay their chief and six of their

fellows.

Though he had lived without honor, thus he died,

like a man, brave and repentant, and rectifying evil. Nor was his body

dishonored. For that he fought greatly, and slew their own chieftain, they

respected him and gave him a warrior's burial. And because they were a simple

people, who had never seen white men, they were wont to speak of him, as the

seasons passed, as "the strange god who came down out of the sky to

die."

From the November 4, 1926 issue of The Youth's Companion magazine.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.