Jack London Bookstore

Jack London Bookstore

![]()

GOBOTO the traders come off their schooners and the planters drift in from far

wild coasts, and one and all they assume shoes, white duck trousers and various

other appearances of civilization. At Goboto mail is received, bills are paid,

and newspapers, rarely more than five weeks old, are accessible; for the little

island, belted with its coral reefs, affords safe anchorage, is the steamer

port of call, and serves as the distributing point for the whole wide-scattered

group.

GOBOTO the traders come off their schooners and the planters drift in from far

wild coasts, and one and all they assume shoes, white duck trousers and various

other appearances of civilization. At Goboto mail is received, bills are paid,

and newspapers, rarely more than five weeks old, are accessible; for the little

island, belted with its coral reefs, affords safe anchorage, is the steamer

port of call, and serves as the distributing point for the whole wide-scattered

group.

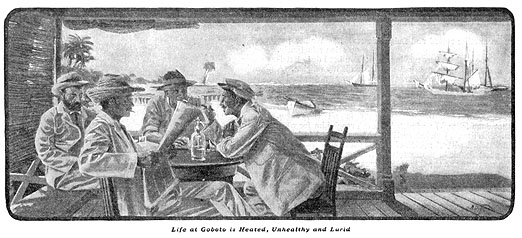

Life at Goboto is heated, unhealthy and lurid,

and for its size it asserts the distinction of more cases of acute alcoholism

than any other spot in the world. Guvutu, over in the Solomons, claims that it

drinks between drinks. Goboto does not deny this. It merely states, in passing,

that in the Goboton chronology no such interval time is known. It also poins

out its import statistics, which show a far larger per capita consumption of

liquors. Guvutu explains this on the basis that Goboto does a larger business

and has more visitors. Goboto retorts that its population is smaller and that

its visitors are thirstier. And the discussion goes on interminably,

principally because the disputants do not live long enough to settle it.

Goboto is not large. The island is only a quarter

of a mile in diameter, and on it are situated an Admiralty coalshed—where

a few tons of coal have lain untounched for twenty years—the barracks for

a handful of black laborers, a big store and warehouse with sheet-iron roofs,

and a bungalow inhabited by the manager and his two clerks. They are the white

population. An average of one man out of the three is always to be found down

with fever. It is the policy of the company to treat its patrons well, as

invading companies have found out, and it is the task of the manager and clerks

to do the treating. Throughout the year traders and recruiters arrive from far

dry cruises and planters from equally distant and dry shores, bringing with

them magnificent thirsts. Goboto is the Mecca of sprees, and when they have

spreed they go back to their schooners and plantations to recuperate.

Some of the less hardy require as much as six

months between visits. But for the manager and his assistants there are no such

intervals. They are on the spot, and week by week, blown in by monsoon or

southeast trade, the schooners come to anchor, cargoed with copra, ivory, nuts,

pearl shell, hawksbill turtle and thirst.

It is a very hard job at Goboto. That is why the

pay is twice that on other stations, and that is why the company selects only

courageous and intrepid men for this particular station. They last no more than

a year or so, when the wreckage of them is shipped back to Australia, or the

remains of them are buried in the sand across on the windward side of the

islet. Johnny Bassett, almost the legendary hero of Goboto, broke all records.

He was a remittance man with a remarkable constitution and he lasted seven

years.

Nevertheless, at Goboto they tried to be

gentlemen. For that matter, though something was wrong with them, they were

gentlemen and had been gentlemen. That was why the great unwritten rule of

Goboto was that visitors should put on pants and shoes. Breech-clouts,

lavalavas and bare legs were not tolerated. When Captain Jensen, the wildest of

the blackbirders though descended from old New York Knickerbocker stock, surged

in, clad in loin-cloth, undershirt, two belted revolvers and a sheath-knife, he

was stopped at the beach. This was in the days of Johnny Bassett, ever a

stickler in matters of etiquette. Captain Jensen stood up in the sternsheets of

his whaleboat and denied the existence of pants on his schooner. Also he

affirmed his intention of coming ashore. They of Goboto nursed him back to

health from a bullet-hole through his shoulder, and in addition handsomely

begged his pardon, for no pants had they found on his schooner. And finally, on

the first day he sat up, Johnny Bassett kindly but firmly assisted his guest

into a pair of pants on his own. This was the great precedent. In all the

succeeding years it had never been violated. White men and pants were

undivorceable. Only n----rs ran naked.

ON THIS night things were, with one exception, in nowise

different from any other night. Seven of them with glimmering eyes and steady

legs had capped a day of Scotch with swivelsticked cocktails and sat down to

dinner. Jacketed, trousered and shod they were: Jerry McMurtrey, the manager;

Eddy Little and Jack Andrews, clerks; Captain Stapler, of the recruiting ketch

Merry; Darby Shryleton, planter from Tito-Ito; Peter Gee, a half-caste Chinese

pearl-buyer who ranged from Ceylon to the Paumotas; and Alfred Deacon, a

visitor who had stopped off from the last steamer. At first wine was served by

the black servants to those who drank it, though all quickly shifted back to

Scotch and soda—pickling their food as they ate it ere it went into their

calcined, pickled stomachs.

Over their coffee they heard the rumble of an

anchor-chain through a hawspipe, tokening the arrival of a vessel.

"It's David Grief," Peter Gee

remarked.

"How do you know?" Deacon demanded

truculently, and then went on to deny the half-caste's knowledge. "You

chaps put on a lot of side. I've done some sailing myself, and this naming a

craft when its sail is only a blur, or naming a man by the sound of his

anchor—it's—it's unadulterated poppycock."

Peter Gee was engaged in lighting a cigarette and

did not answer.

"Some of the n----rs do amazing things that

way," McMurtrey interposed tactfully.

As with the others, this conduct of their visitor

jarred on the manager. From the moment of Peter Gee's arrival that afternoon

Deacon had manifested a tendency to pick on him. He had disputed his statements

and been generally rude.

"Maybe it's because Peter's got Chink blood

in him," had been Andrews' hypothesis. "Deacon's Australian, you

know, and they're daffy down there on color."

"I fancy that's it," McMurtrey had

agreed. "But we can't permit any bullying, especially of a man like Peter

Gee, who's whiter than most white men."

In this the manager had been in nowise wrong.

Peter Gee was that rare creature, a good as well as clever Eurasian. In fact it

was the stolid integrity of the Chinese blood that toned the recklessness and

licentiousness of the English blood that had run in his father's veins. Also he

was better educated than any man there, spoke better English as well as several

other tongues, and knew and lived more of their own ideals of gentlemanliness

than they did themselves. And, finally, he was a gentle soul. Violence he

deprecated, though he had killed men in his times. Turbulence he abhorred. He

avoided turbulence as he would the plague.

Captain Stapler stepped in to help McMurtrey:

"I remember when I changed schooners and

came into Altman the n----rs knew right off the bat it was me. I wasn't

expected, either, much less was I expected to be in another craft. They told

the trader it was me. He used the glasses and wouldn't believe them. But they

did know. Told me afterward they could see it sticking out all over the

schooner that I was running her."

Deacon ignored him and returned to the attack on

the pearl-buyer.

"How did you know from the sound of the

anchor that it was this whatever-you-called-him man?" he challenged.

"There are so many things that go to make up

such a judgment," Peter Gee answered. "It's very hard to explain. It

would require almost a textbook."

"I thought so," Deacon sneered.

"Explanation that doesn't explain is easy."

"Who's for bridge?" Eddy Little, the

second clerk, interrupted, looking up expectantly and starting to shuffle.

"You'll play, won't you, Peter?"

"If he does, he's a bluffer," Deacon

cut back. "I'm getting tired of all this poppycock. Mr. Gee, you will

favor me and put yourself in a better light if you tell how you know who that

man was that just dropped anchor. After that I'll play you piquet."

"I'd prefer bridge," Peter answered.

"As for the other thing, it's something like this: By the sound it was a

small craft—no square-rigger. No whistle, no siren was blown—again

a small craft. It anchored close in—still again a small craft, for

steamers and big ships must drop hook outside the middle shoal. Now the

entrance is tortuous. There is no recruiting nor trading captain in the group

who dares to run the passage after dark. Certainly no stranger would. There

were two exceptions. The first was Margonville. But he was executed by the High

Court at Fiji. Remains the other exception, David Grief. Night or day in any

weather he runs the passage. This is well know to all. A possible factor, in

case Grief were somewhere else, would be some young dare-devil of a skipper. In

that connection, in the first place, I don't know of any, nor does anybody

else. In the second place, David Grief is in these waters, cruising on the

Gunga, which is shortly scheduled to leave here for Karo-Karo. I spoke Grief on

the Gunga in Sandfly Passage day before yesterday. He was putting a trader

ashore on a new station. He said he was going to call in at Babo and then come

on to Goboto. He has had ample time to get here. I have heard an anchor drop.

Who else than David Grief can it be? Captain Donovan is skipper of the Gunga,

and him I know too well to believe that he'd run in to Goboto after dark unless

his owner were in charge. In a few minutes David Grief will enter through that

door and say: 'In Guvutu they merely drink between drinks.' I'll wager fifty

pounds he's the man that enters and that his word will be: 'In Guvutu they

merely drink between drinks.'"

Deacon was for the moment crushed. The sullen

blood rose darkly in his face.

"Well, he's answered you," McMurtrey

laughed genially. "And I'll back his bet myself for a couple of

sovereigns."

"Bridge!—who's going to take a

hand?" Eddy Little cried impatiently. "Come on, Peter."

"The rest of you play," Deacon said.

"He and I are going to play piquet."

"I'd prefer bridge," Peter Gee said

mildly.

"Don't you play piquet?"

Peter nodded.

"Then come on. Maybe I can show I know more

about that than I do about anchors."

"Oh, I say—" McMurtrey began.

"You can play bridge," Deacon shut him

off. "We prefer piquet."

Reluctantly Peter Gee was bullied into a game

that he knew would be unhappy.

"Only a rubber," he said, as he cut for

deal.

"For how much?" Deacon asked.

Peter Gee shrugged his shoulders. "As you

please."

"Hundred up—five pounds a

game?"

Peter Gee agreed.

"With the lurch double, of course, ten

pounds?"

"All right," said Peter Gee.

At another table four of the others sat in at

bridge. Captain Stapler, who was no card-player looked on. McMurtrey, with

poorly concealed apprehension, followed as well as he could what went on at the

piquet table. His fellow Englishmen as well were shocked by the behavior of the

Australian, and all were troubled by fear of some untoward act on his part.

That he was working up his animosity against the half-caste and that the

explosion might come any time was apparent to all.

"I hope Peter loses," McMurtrey said in

an undertone.

"He won't if he has any luck," Andrews

answered. "He's a wizard at piquet. I know by experience."

That Peter Gee was lucky was patent from the

continual badgering of Deacon, who filled his glass frequently. He had lost the

first game handily and, judging from his remarks, was about to lose the second,

when the door opened and David Grief entered.

"In Guvutu they merely drink between

drinks," he remarked casually to the assembled company ere he gripped the

manager's hand. "Hello, Mac! Say, my skipper's down in the whaleboat. He's

got a silk shirt, a tie and tennis shoes all complete, but he wants you to send

a pair of pants down. Mine are too small, but yours will fit him. Hello, Eddy,

how's that gari-gari? You up, Jack? The miracle has happened. No one

down with fiver." He sighed happily. "I suppose the night is still

young. Hello, Peter, did you catch that big squall an hour after you left us?

We had to let go the second anchor."

While David Grief was being introduced to Deacon,

McMurtrey dispatched a house-boy with the indispensable pants, and when Captain

Donovan finally came into the room he was garbed as a white man should

be—at least in Goboto.

Deacon lost the second game, and an outburst

heralded the fact. Peter Gee devoted himself to lighting a cigarette and

keeping quiet.

"What?—are you quitting because you're

ahead?" Deacon demanded.

Grief raised his eyebrows questioningly to

McMurtrey who frowned back his own disgust.

"It's the rubber," Peter Gee

answered.

"It takes three games to make a rubber. It's

my deal. Come on."

Peter Gee acquiesced and the third game was

on.

"Young whelp—he needs a lacing,"

McMurtrey muttered to Grief. "Come on, let us quit, you chaps. I want to

keep an eye on him. If he goes too far I'll throw him out on the beach, company

instructions or no."

"Who is he?" Grief queried.

"A left-over from last steamer. Company's

orders to treat him nice. He's looking to invest in a plantation. Has a

ten-thousand-pound letter of credit with the company. He's got 'all-white

Australia' on the brain. Thinks because his skin is white and because his

father was once Attorney-General of the Commonwealth that he can be a cur.

That's why he's picking on Peter, and you know Peter's the last man in the

world to make trouble or incur trouble. Confound the company! I didn't engage

to look after infants with bank accounts. Come on, fill your glass, Grief. The

man's a blighter, a blithering blighter."

"Maybe he's only young," Grief

suggested.

"He can't contain his drink—that's

clear." The manager glared his disgust and wrath. "If he raises a

hand to Peter, so help me, I'll give him a licking myself—the little,

overgrown cad!"

The pearl-buyer pulled the pegs out of the

cribbage board on which he was scoring and sat back. He had won the third game.

He glanced across to Eddy Little, saying:

"I'm ready for the bridge now."

"I wouldn't be a quitter," Deacon

snarled.

"Oh, really, I'm tired of the game,"

Peter Gee assured him with his habitual quietness.

"Come on and be game," Deacon bullied.

"One more. You can't take my money that way. I'm out fifteen pounds.

Double or quits."

McMurtrey was about to interpose, but Grief

restrained him with his eyes.

"If it positively is the last, all

right," said Peter Gee, gathering up the cards. "It's my deal, I

believe. As I understand it, this final is for fifteen pounds. Either you owe

me thirty or we quit even?"

"That's it. Either we break even or I pay

you thirty."

"Getting blooded, eh?" Grief

remarked.

The other men stood or sat around the table and

Deacon played again in bad luck. That he was a good player was clear. The cards

were merely running against him. That he could not take his ill luck with

equanimity was equally clear. He was guilty of sharp, ugly curses and he

snapped and growled at the imperturbable half-caste. In the end Peter Gee

counted out, while Deacon had not even made his fifty points. He glowered

speechlessly at his opponent.

"Looks like a lurch," said Grief.

"I must always remember that one man is as

good as another, save and except when he thinks he is better.

At the beginning of the reading Deacon's face had

gone white with anger. Then had arisen, from neck to forehead, a slow and

terrible flush that deepened to the end of the reading.

Back to the Jack London Bookstore First Editions.

"Which is double," said Peter Gee.

"There's no need your telling me,"

Deacon snarled; "I've studied arithmetic. I owe you forty-five pounds.

There, take it!"

The way in which he flung the nine five-pound

notes on the table was an insult in itself. Peter Gee was even quieter and flew

no signals of resentment.

"You've got fool's luck but you can't play

cards," Deacon went on. "I could teach you cards."

The half-caste smiled and nodded acquiescence as

he folded up the money.

"There's a little game called casino; I

wonder if you ever heard of it—a child's game?"

"I've seen it played," the half-caste

murmured gently.

"What's that?" was the resulting snap

from Deacon. "Maybe you think you can play it!"

"Oh, no, not for a moment! I'm afraid I

haven't head enough for it."

"It's a bully game, casino," Grief

broke in pleasantly. "I like it very much."

Deacon ignored him.

"I'll play you ten quid a

game—thirty-one points out," was the challenge to Peter Gee.

"And I'll show you how little you know about cards. Come on, where's a

full deck?"

"No, thanks," the half-caste answered.

"They are waiting for me in order to make up a bridge set."

"Yes, come on," Eddy Little begged

eagerly. "Come on, Peter, let's get started."

"Afraid of a little game like casino!"

Deacon girded. "Maybe the stakes are too high. I'll play you for

pennies—or farthings, if you say so."

The man's conduct was a hurt and an affront to

all of them. McMurtrey could stand it no longer.

"Now hold on, Deacon. He says he doesn't

want to play. Let him alone."

Deacon turned raging upon his host; but before he

could blurt out his abuse Grief stepped into the breach.

"I'd like to play casino with you," he

said.

"What do you know about it?"

"Not much, but I'm willing to

learn."

"Well, I'm not teaching for pennies

tonight."

"Oh, that's all right," Grief answered.

"I'll play for almost any sum—within reason, of course."

Deacon proceeded to dispose of this intruder with

one stroke.

"I'll play you a hundred pounds a game, if

that will do you any good."

Grief beamed his delight. "That will be all

right—very right. Let us begin. Do you count sweeps?"

Deacon was taken aback. He had not expected a

Goboton trader to be anything but crushed by such a proposition.

"Do you count sweeps?" Grief

repeated.

Andrews had brought him a new deck, and he was

throwing out the joker.

"Certainly not," Deacon said.

"That's a sissy game."

"I'm glad," Grief coincided. "I

don't like sissy games, either."

"You don't, eh? Well, then, I'll tell you

what we do. We'll play for five hundred pounds a game."

"I'm agreeable," Grief said, beginning

to shuffle. "Cards and spades go out first, of course, and then big and

little casino, and the aces in the bridge order of value. Is that

right?"

"You're a lot of jokers down here,"

Deacon laughed, but his laughter was strained. "How do I know you've got

the money?"

"By the same token I known you've got it.

Mac, how's my credit with the company?"

"For all you want," the manager

answered.

"You personally guarantee that?" Deacon

demanded.

"I certainly do," McMurtrey said.

"Depend upon it, the company will honor his paper up to and past your

letter of credit."

"Low deals," Grief said, placing the

deck before Deacon.

The latter hesitated in the midst of the cut and

looked around with querulous misgiving at the faces of the others. The clerks

and captains nodded.

"You're all strangers to me," Deacon

complained. "How am I to know? Money on paper isn't always the real

thing."

Then it was Peter Gee, drawing a wallet from his

pocket and borrowing a fountain pen from McMurtrey, went into action.

"I haven't gone to buying yet," the

half-caste explained, "so the account is intact. I'll just indorse it over

to you, Grief. It's for fifteen thousand. There, look at it."

"Yes. It's just the same as your own and

just as good. The company's paper is always good."

Deacon cut the cards, won the deal and gave them

a thorough shuffle. But his luck was still against him and he lost the

game.

"Another game," he said. "We

didn't say how many, and you can't quit with me a loser. I want

action."

Grief shuffled and passed the cards for the

cut.

"Let's play for a thousand," Deacons

said when he had lost the second game. And when the thousand had gone the way

of the two five-hundred bets he proposed to play for two thousand.

"That's progression," McMurtrey warned,

and was rewarded by a glare from Deacon. But the manager was insistent.

"You don't have to play progression, Grief, unless you're

foolish."

"Who's playing this game?" Deacon

flamed at his host; and then, to Grief: "I've lost two thousand to you.

Will you play for two thousand?"

Grief nodded, the fourth game began and Deacon

won. The manifest unfairness of such betting was known to all of them. Though

he had lost three games out of four Deacon had lost no money. By the child's

device of doubling his wager with each loss he was bound, with the first game

he won, no matter how long delayed, to be even again.

He now evinced an unspoken desire to stop, but

Grief passed the deck to be cut.

"What?" Deacon cried. "You want

more?"

"Haven't got anything yet," Grief

murmured whimsically, as he began the deal. "For the usual five hundred, I

suppose?"

The shame of what he had done must have tingled

in Deacon, for he answered: "No, we'll play for a thousand. And say!

Thirty-one points is too long. Why not twenty-one points out—if it isn't

too rapid for you?"

"That will make it a nice quick little

game," Grief agreed.

The former method of play was repeated. Deacon

lost two games, doubled the stake and was again even. But Grief was patient,

though the thing occurred several times in the next hour's play. Then happened

what he was waiting for—a lengthening in the series of losing games for

Deacon. The latter doubled to four thousand and lost, doubled to eight thousand

and lost, and then proposed the double to sixteen thousand.

Grief shook his head. "You can't do that,

you know. You've only ten thousand credit with the company."

"You mean you won't give me action?"

Deacon asked hoarsely. "You mean that with eight thousand of my money

you're going to quit?"

Grief smiled and shook his head.

"It's robbery, plain robbery," Deacon

went on. "You take my money and won't give me action."

"No, you're wrong. I'm perfectly willing to

give what action you've got coming to you. You've got two thousand pounds of

action yet."

"Well, we'll play it," Deacon took him

up. "You cut."

The game was played in silence, save for

irritable remarks and curses from Deacon. Silently the onlookers filled and

sipped their long Scotch glasses. Grief took no notice of his opponent's

outbursts, but concentrated on the game. He was really playing cards, and there

were fifty-two in the deck to be kept track of and of which he did keep track.

Two-thirds of the way through the last deal he threw down his hand.

"Cards put me out," he said. "I

have twenty-seven."

"If you've made a mistake!" Deacon

threatened, his face white and drawn.

"Then I shall have lost. Count

them."

Grief passed over his stack of takings, and

Deacon with trembling fingers verified the count. He half shoved his chair back

from the table and emptied his glass. He looked about him at unsympathetic

faces.

"I fancy I'll be catching the next steamer

for Sydney," he said, and for the first time his speech was quiet and

without bluster.

As Grief told them afterward: "Had he whined

or raised a roar I wouldn't have given him that last chance. As it was he took

his medicine like a man, and I had to do it."

Deacon glanced at his watch, simulated a weary

yawn and started to rise.

"Wait," Grief said. "Do you want

further action?"

The other sank down in his chair, strove to speak

but could not, licked his dry lips and nodded his head.

"Captain Donovan here sails at daylight in

the Gunga for Karo-Karo," Grief began with seeming irrelevance.

"Karo-Karo is a ring of sand in the sea, with a few thousand cocoanut

trees. Pandanus grows there, but they can't grow sweet potatoes or taro. There

are about eight hundred natives, a king and two prime minsters, and the last

three named are the only ones who were any clothes. It's a sort of God-forsaken

little hole and once a year I send a schooner up from Goboto. The drinking

water is brackish, but old Tom Butler has survived on it for a dozen years.

He's the only white man there, and he has a boat's crew of five Santa Cruz boys

who would run away or kill him if they could. That is why there were sent

there. They can't run away. He is always supplied with the hard cases from the

plantations.

"Naturally you are wondering what it is all

about. But have patience. As I have said, Captain Donovan sails on the annual

trip to Karo-Karo at daylight tomorrow. Tom Butler is old and getting quite

helpless. I've tried to retire him to Australia, but he says he wants to remain

and die on Karo-Karo, and he will in the next year or so. He's a queer old

codger. Now the time is due for me to send some white man up to take the work

off his hands. I wonder how you'd like the job. You'd have to stay two

years.

"Hold on, I've not finished. You've talked

frequently of action this evening. There's no action in betting away what

you've never sweated for. The money you've lost to me was left you by your

father or some other relative who did the sweating. But two years of work as

trader on Karo-Karo would mean something. I'll bet the ten thousand I've won

from you against two years of your time. If you win, the money's yours. If you

lose, you take the job at Karo-Karo and sail at daylight. Now that's what might

be called real action. Will you play?"

Deacon could not speak. His throat lumped and he

nodded his head as he reached for the cards.

"One thing more," Grief said. "I

can do even better. If you lose, two years of your time are

mine—naturally without wages. Nevertheless, I'll pay you wages. If your

work is satisfactory, if you observe all instructions and rules, I'll pay you

five thousand pounds a year for two years. The money will be deposited with the

company, to be paid to you with interest when the time expires. Is that all

right?"

"Too much so," Deacon answered.

"You are unfair to yourself. A trader only gets ten or fifteen pounds a

month."

"Put it down to action then," Grief

said with an air of dismissal. "And before we begin I'll jot down several

of the rules. These you will repeat aloud every morning during the two

years—if you lose. They are for the good of your soul. When you have

repeated them aloud seven hundred and thirty Karo-Karo mornings I am confident

they will be in your memory to stay. Lend me your pen, Mac. Now, let's

see."

He wrote steadily and rapidly for some minutes,

then proceeded to read the matter aloud:

"No matter how drunk I am I must not fail to

be a gentleman. A gentleman is a man who is gentle. Note: It would be better

not to get drunk.

"A good curse, rightly used and rarely, is

an efficient thing. Too many curses spoil the cursing. Note: A curse cannot

change a card sequence nor cause the wind to blow.

"There is no license for a man to be less

than a man. Ten thousand pounds cannot purchase such a license."

"There, that will be all," Grief said,

as he folded the paper and tossed it to the center of the table. "Are you

still ready to play the game?"

"I deserve it," Deacon muttered

brokenly. "I've been an ass! Mr. Gee, before I know whether I win or lose

I want to apologize. Maybe it was the whisky, I don't know, but I'm an ass, a

cad, a bounder—everything that's rotten."

He held out his hand and the half-caste took it

beamingly.

"I say, Grief," he blurted out,

"the boy's all right. Call the whole thing off and let's forget it in a

final nightcap."

Grief showed signs of debating, but Deacon

cried:

"No; I won't permit it. I'm not a quitter.

If it's Karo-Karo, it's Karo-Karo. There's nothing more to it."

"Right," said Grief, as he began the

shuffle. "If he's the right stuff to go to Karo-Karo, Karo-Karo won't do

him any harm."

The game was close and hard. Three times they

divided the deck between them and "cards" was not scored. At the

beginning of the fifth and last deal Deacon needed three points to go out and

Grief needed four. "Cards" alone would put Deacon out, and he played

for "cards." He no longer muttered or cursed, and played his best

game of the evening. Incidentally he gathered in the two black aces and the ace

of hearts.

"I suppose you can name the four cards I

hold," he challenged, as the last of his deal was exhausted and he picked

up his hand.

Grief nodded.

"Then name them."

"The knave of spades, the deuce of spades,

the tray of hearts and the ace of diamonds," Grief answered.

Those behind Deacon and looking at his hand made

no sign. Yet the naming had been correct.

"I fancy you play casino better than

I," Deacon acknowledged. "I can name only three of yours, a knave,

and ace and big casino."

"Wrong. There aren't five aces in the deck.

You've taken in three and you hold the fourth in your hand now."

"By Jove, you're right," Deacon

admitted. "I did scoop in three. Anyway, I'll make 'cards' on you. That's

all I need."

"I'll let you save little

casino—" Grief paused to calculate. "Yes, and the ace as well,

and I'll make 'cards' and go out with big casino. Play."

"No 'cards,' and I win!" Deacon exulted

as the last of the hand was played. "I go out on little casino and the

four aces. Big casino and 'spades' only bring you to twenty."

Grief shook his head. "Some mistake, I'm

afraid."

"No," Deacon declared positively.

"I counted every card I took in. That's the one thing I was correct on.

I've twenty-six and you've twenty-six."

"Count again," Grief said.

Carefully and slowly, with trembling fingers,

Deacon counted the cards he had taken. There were twenty-five. He reached over

to the corner of the table, took up the rules Grief had written, folded them

and put them in his pocket. Then he emptied his glass and stood up. Captain

Donovan looked at his watch, yawned and also arose.

"Going aboard, Captain?" Deacon

asked.

"Yes," was the answer. "What time

shall I send the whaleboat for you?"

"I'll go with you now. We'll pick up my

luggage from the Billy as we go by. I was wailing on her for Babo in the

morning."

Deacon shook hands all around, after receiving a

final pledge of good luck on Karo-Karo.

"Does Tom Butler play cards?" he asked

Grief.

"Solitaire," was the answer.

"Then I'll teach him double solitaire."

Deacon turned toward the door where Captain waited, and added with a

sigh—"And I fancy he'll skin me, too, if he plays like the rest of

you island men."

From the September 30, 1911 issue of The Saturday Evening Post magazine.